This week, the world of Wikipedia was briefly thrown into a tizzy due to a selfie taken by a monkey.

In a transparency report released on Wednesday, the crowdsourced online encyclopedia detailed an extremely peculiar takedown request made by British photographer David Slater. Slater was in a park in North Sulawesi, Indonesia, when a crested back macaque briefly stole his camera and did what anyone would do in that situation—snap a selfie.

?The pictures were featured in an online newspaper article and eventually posted to [Wikimedia] Commons,” the report read. ?We received a takedown request from the photographer, claiming that he owned the copyright to the photographs. We didn’t agree, so we denied the request.”

Wikipedia’s logic in denying Slater’s request is, because the monkey—a “non-human animal”— took the picture, and because non-humans can’t legally hold intellectual property, any photo taken by a money goes directly into the public domain. (For the record, Wikipedia never said the monkey owned the copyright, as countless Internet commentators claimed.)

The back-and-forth over who owns the rights to the photo is interesting in it’s own right. But a quick search through other images on Wikipedia involving animal creations reveals an even thornier question.

It’s one thing if a monkey grabs a camera and accidentally hits the button to take a selfie (you can tell it was an accident because the monkey didn’t even apply a tasteful Instagram filter), but what happens when the work in question is significantly more deliberate?

In other words, under this system, who owns the rights to a painting made by a horse?

This is not as ridiculous a question as it may seem. Paintings made by animals, which seem to universally be in the style of abstract impressionism, aren’t uncommon. Like the monkey selfie, most of these pieces of animal-made art appear on Wikipedia under a public domain license.

This work is by Congo, a chimpanzee who became famous in the 1950s for his painting ability:

There is also this painting by Kissu the horse:

Or this painting, made by a Jack Russel terrier named Tillamook Cheddar, who has had at least 20 solo exhibitions of her work, and Parade Magazine once labeled her America’s “best new artist”:

And don’t forget this work by Ruby the elephant, a pachyderm living at the Phoenix Zoo whose works have fetched price tags up to $25,000:

Wikipedia’s interpretation of copyright law isn’t held universally. There are some instances where copyright is actually attributed to an animal artist in a consequential way.

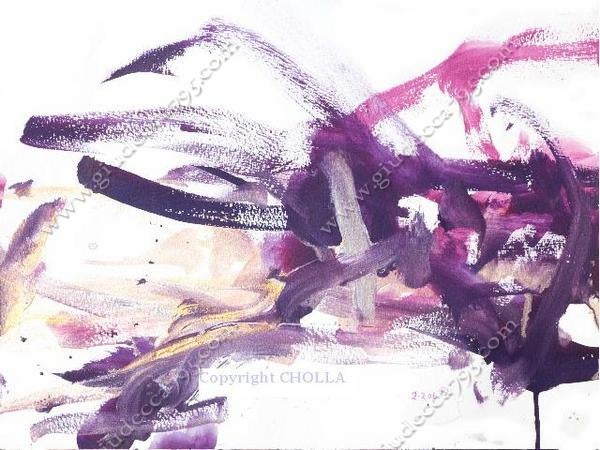

After winning an honorable mention in an international art competition, the work of a mustang-quarterhorse mix named Cholla was exhibited at the Giudecca 795 Art Gallery in Venice, Italy, in 2009. Some remnants of that exhibition are still left online and they carry watermarks indicating that Cholla holds the copyright to his Jackson Pollock-esque paintings:

According to Parker Higgins, an activist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) specializing in intellectual property, the question of who, if anyone, holds the rights to photographs taken by animals is likely a good bit more cut-and-dry than those of paintings created by animal artists.

?Wikipedia’s argument absolutely makes sense,” Higgins explained. ?There’s a very strong case that [the monkey selife] is not subject to copyright because there’s no human author. That sort of question hasn’t been litigated too often, but it follows both the law and the Copyright Office’s guidelines for what it will accept registration on.”

?In the case of Ruby the Elephant, it could maybe get a little more complicated,” he continued. ?As far as I understand it, elephant painters follow their training very exactly, so the placement of the strokes on the page are the same every time, and set by the trainer, not the animal. It’d be a real edge case if those copyright questions were ever litigated, but it might look a little different from the monkey selfie.”

That said, a commenter on a GigaOm article about the monkey selfie adds a relevant twist:

If the law says the monkey doesn’t count as a creator then the point at which the photo was taken isn’t the point at which a work was created. It’s a force majeure kinda thing at that stage. The photographer effectively created the work at the point he processed the image. At that point a chance occurrence became a work.

…

As far as I can figure U.S. copyright law, the work was created by the photographer because the monkey is incapable of creating a work. Effort was expended by the photographer in the production of the work both before and after the monkey’s involvement.

Applied to the context of a painting composed by a furry fingers (or by a long, limber trunk), this line of thinking would imply that an animal’s painting would be public domain until someone snapped a picture of it and then scanned it that image into a computer, when that person would then hold the copyright.

Or, as this tweet elegantly summarizes the situation:

The Internet is actually just a giant experiment to make us rethink our ideas about intellectual property. https://t.co/fVaEFczl8q

— John Burger (@johndburger) August 6, 2014

Photo via Jennifer Carole/Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)