This story was produced by Tumblr Storyboard, Tumblr’s in-house editorial arm.

There are an estimated 6,700 to 6,900 languages in the world today, and they drift through the air like a meteorological echo—Hello! Hallo! Allô!—a roll of thunder or a set of bird calls off in the corner of the ear and the eye. And accompanying every tongue are loanwords, or, rather, lehnwerts, the tin-eared telephone line tossed from house to house, the improvised bridge of a tree knocked across a river’s expanse, or, more prosaically, words one “borrows” from one language into another. Loanwords explain how and why English speakers can say things like Frankfurter, pretzel, hinterland, dreck, or kaput without their conversational co-conspirator batting an eye.

Loanwords imply a certain baseline of connectivity. Though it’s hard to imagine one unified language, a transnational tongue in which all the work is finished and everything is “just so,” it’s equally difficult to imagine a language perfectly shattered. To weave between the two means not only wandering into a news kiosk with newspapers from all over the world—as I’m currently doing in Harvard Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts—but enlisting the Tumblr community, too, whether they’re chronicling “Polyglot Problems”—

—or whether they’re just an average citizen, like Cheila Sousa—a student in Portugal who had caught a cold, and—in her words—“now wears big sweaters, scarfs, and tissues all the time.”

As for linguistic activity already happening, you can see Mehreen Kasana translate “Haters gonna hate” into Urdu as “Nafrat karne walay nafrat karain ge.” You can watch one blogger try to say “Good night” in Khmer — the language of Cambodia—by saying “Reil drai soos day” and read the confused hotel staff’s reply, “… real dry Tuesday?” Otherwordly blogs about untranslatable words like “kintsukuroi.” Lingua Fandom re-blogs the idea of keyboard smashes being dubbed “typerventilating.” Rzeczpospolita Polskablogs out individual Polish words, like “Biba” (party) or “Mnie to rybka” (literally—“It’s a fish to me,” but it means, “I don’t care”). One blogger started The Polyglot Playlist and told me that they enjoyed catching phrases more common to vernacular than what the dictionary said and ordained, i.e., “In one Arabic song a woman says a man’s eyes look like ‘a painting drawn in childhood.’ Its literal meaning is confusing when translated, but in Arabic it means that he has ‘innocent eyes’ or he is ‘childishly innocent (naive.)’”

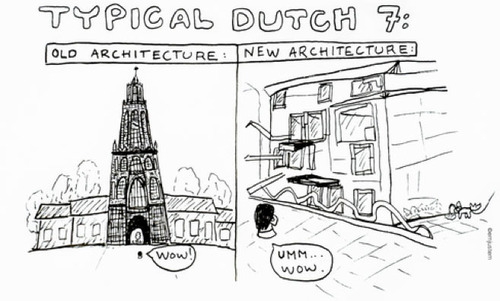

If we start the figurative daisy chain with German—the language of Goethe, Schiller, Casper, Prinz Pi, Sebald, and others, the language of the “Blaue Stunde” and “Seeräuberjenny”—and ask a German teenager of a word both simultaneously German and Dutch that comes to mind, we get “helden,” heroes, which in turn summons phrases like, “Een held op sokken” (a hero without socks), or the gently chastising “Du bist mir vielleicht ein Held” (“You are to me, perhaps, a hero”); and if we ask Dutch student Ceyda Dilek—Dutch being the language of “Honkbal” (which came about in defiance of German occupiers and fills the summer soccer gap), Van Gogh, fietsen, and Harry Mulisch—for a word simultaneously French and Dutch, we get “etage” (“floor,” which is étage in French). And which—in part—brings to mind the work of Heidi, who sketched this out—

—and has more like it on her blog. If we reach out to someone in France — French being the language of Ben L’Oncle Soul and the European Court of Justice and people who argue like dopes about Celine on shows about books — and we ask for a word in Romanian, we could get “Eugène Ionesco” or “Tristan Tzara,” but we could get masculin, feminin, bebe, a construi and construire, and a whole host of others; and if we ask a Romanian — Romanian being the language of youthful words, as one blogger pointed out to me, like “jumbix” and “smardoi” (“fellow” and “fight”), and old words too, like bălan (blond) and vârtos (imposing because of muscle mass)—for a word simultaneously Romanian and Turkish, we get talaz (wave) and dovleak/dövlek (pumpkin). If we ask a Turk—Turkish being the language of Yakup Kadri, Resat Nuri, Halide Edip, Aka Gunduz, Faruk Nafiz, Orhan Seyfi, of Ataturk reading a book by the Hungarian linguist Gyula Nemeth and seeing a Latinized Turkish as the way to go forward in the century, of Fenerbahçe chants filling the stands — for a word simultaneously Turkish and Persian, we get lutfen and lutfan (لطفا), as in, “Please,” or “hava” (هوا) which means, “air/weather”; and if ask an Iranian for a word that is the same in both Farsi and Arabic, we get ketab and kutub (book), or—as it should be written —كتاب and كتب; and if we ask Anna for a word in both Arabic and Hebrew, we get “Yalla Balagan,” which Anna—who blogs at Fire in the Heart—told me is used by Israelis so much, “and it means, basically, like, ‘Let’s go crazy,’ and ‘yalla’ is Arabic—‘balagan,’ I think, is originally Persian” (though that is a bit of a cheat). And if we want to take a break before we tug at another portion of the daisy chain, we can switch to ASL, American Sign Language, and move our hands in the silence (to play off the idea of “typerventilating.” One Tumblr user realized that if they learned ASL, they could do “visual keymash”), a language which deals with loanwords just the same as any other, whether it’s in watching Stephen Fry’s Planet Word to see how you say “Obama” (an “O” turning over and becoming an American flag flapping in the wind) or in breaking down fingerspellings into current usage, i.e., “B-A-C-K” becoming “B-K,” or the verb “to train” becoming “practice” with the letter ‘T’ at the front, “society” becoming S + “group,” or “twin” becoming T + “to be born,” as Julie Weisenberg at SUNY Stony Brook points out in an excellent paper.

Some would argue that the gaps are already somewhat apparent, and that’s partially true. You can’t walk “etage” from one side of a country’s border to the other and expect life to crack golden and open in front of you like a great ephemeral egg.

Yet it’s also worth noting that there are thousands and thousands of flights per day. Borders are repeatedly crossed with elan. In 2008, there are some estimates that put worldwide commercial flights at 93,000 per day; this year, there are some estimates that put it topping 100,000. That has a consequence for language. Sixty million people pass through Heathrow Airport outside London every year, which means it and others like it are a place where—as one photographer who had a ten-hour layover in Tokyo after visiting Catalunya told me—one can “practice speaking other languages, even if it’s only a few words, to ask for a bottle of water or a sandwich, for example.”

In the Netherlands, for instance, there’s a library smack dab in the middle of Schiphol Airport. Simple practice of briarpatch words has a chance to explode into an out-and-out forest. The librarian even has aTwitter account, chronicling when the Turkish books go missing and reappear again and other items of incident.

There you could probably find Shakespeare in every tongue, whether it’s Boris Pasternak—Nobel Prize winner and author of Doctor Zhivago—translating Romeo and Juliet, Antony and Cleopatra, Othello, King Henry IV, Macbeth, and King Lear into Russian, mysteriously excising references to corruption in Hamlet, deflating the sexuality of Hamlet, Cordeilia, Othello, and Desdemona, and translating “Is this a dagger I see before me?” into “Where did you come from, dagger?”. Or whether it’s Nicanor Parra—the great Chilean anti-poet—translating King Lear into lines that swim, i.e., “Este es el maligno Flibbertigibett. / Aparece a la hora de queda / Y se marcha al primer canto del gallo / Transmite la catarata.” Or even Hamlet in Italian, Arabic, or Polish, or King Lear in Hindi or Mandarin, or any of these at all.

But our daisy chain has been left languishing, and we’ve yet to tie other languages to it, like the language that—as Gregory Rabassa—translator of Julio Cortazar, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, Antonio Lobo Antunes, and others—put it, sounds like a kind of string quartet: Portuguese, a language wherein one screenwriter in Lisbon said her favorite phrases included “engolir um sapo,” (as in, swallow a toad, as in, eating crow), “não chegar aos calcanhares de” (to not reach the heels of = to not be nearly as good as), or “pôr o carro à frente dos bois” (get your cart in front of your oxen = to get ahead of yourself); a language where Cheila Sousa said she likes “the way people from Açores talk. The most common Portuguese accents are from there and from Porto—it’s where people talk very differently and are sometimes even hard to understand, which can be somehow funny.”

If we are to look for a word that exists simultaneously in Portuguese and Japanese—Portuguese being the language of Jorge Ben Jor, Gilberto Gil, O Folha de SP, and Sócrates, Japanese being the language of Haruki Murakami and the homeland of haiku and Kurosawa and Ozu and so much more—we can pickcandeia, candle, which is properly written as “カンデヤ” and pronounced the same. And if we are to look for a word that is both Japanese and Korean—Korean being home to a carbon-copy of Saturday Night Live of its own (weirdly and wonderfully)—we can settle our finger on (as they’d write in Japanese) “玉” and (as they’d write in Korean) “다마,” pronounced as “da-ma,” meaning (for a time) “lightbulb,” shifting its meaning to “bead” in Korean, and eventually being consigned to the linga-franca of an older generation that was once occupied by the Japanese, though its meaning is still known today. I had thought of writing out similarities as they are in Romanized script, i.e., “jurumi” meaning “relaxed” or ‘’kagami” (JP) and “kakami” (KR) meaning “mirror,” but that’s not entirely fair.

And if we wish to use a word that’s both Korean and Italian, we can use 비엔날레—or, rather, “biennale,” which are both pronounced the same and mean the same thing (a large art exhibition/festival); and if are to use a word that’s simultaneously Italian and Polish—Italian being the language of clunky atonality and Polish being the language of Jerzy Pilch, Wisława Szymborska, and Kieślowski—we land on tomato, which is “pomodoro” in Italian and “pomidor” in Polish.

“I recommend listening to Polish hooligans and their language,” Karolina Zawadzka — an architecture student tumbling in Warsaw — told me. “We have a word ‘pierdolic’ and it is something like ‘fuck.’ If you want, you can add a few letters and create other words like odpierdol sie (fuck off), pierdol sie (fuck you), napierdolic sie (to get drunk or beat someone) and many more. It’s really common and everyone uses it. But I’m trying to avoid swearing. Women shouldn’t speak like that. … Once, when I was watching tv, a reporter was talking about landing of Dreamliner in Poland. He said he didn’t like the name and proposed to call it ‘Marzenka’ which made me laugh so hard because Marzenka is a diminutive of the Polish name Marzena, constructed of the word marzenia (dreams) and marzyć (to dream.)”

And if we want to leave that behind and use a word that means the same in both Polish and Czech, we get “Wyrok,” as in, “sentence, verdict”; and if we’re looking for a word that exists simultaneously in Czech and Hawaiian—Czech being the mother tongue of Kundera and the stunning Josef Koudelka—we get “pukowi,” as in, “birch tree”; and if we want a word that simultaneously exists in Hawaiian and Spanish, we use “paniolo,” as in, “cowboy.” With Spanish being the language of rapid-fire Chilean, of one Colombian student telling me that a lot of call centers are located in their country because it has the most “neutral” Spanish, of a photographer living in Guatemala telling me that he couldn’t really answer my questions about languages, given that there were 21 different Mayan languages in the country—we are now looking for a word that simultaneously exists in both Spanish and Tagalog, as Tagalog is a common second language of the Philippines, which gives us phrases like bungang-tulog (fruit of sleep) to describe dreams, daga sa dibdib (mouse in the chest) to describe worry, and others—and we get “realidad” and “reina”/”reyna.”

If we want to see a word that exists in both Tagalog and Hindi, we get veranda/baranada and “guro”/गुरु; and if we wish to say something that means the same thing in both Hindi and Urdu, we can say, Mein kamrey main hoon, as in, “I am in the room.” And if we wish to use a word that exists in both Urdu and Punjabi—and here we can zoom in Danny Boyle-like to micro-profile Misha in London speaking a swarm of languages and selling lots and lots of hedgehogs—“my brother bought all of us siblings a hedgehog for Christmas and we didn’t realize they breed like crazy!”—who peppers her sentences in English with Punjabi and Spanish, i.e., “What is this bakwaas, you kamchor? Go make my comida a toda maquina!” (What is this rubbish/nonsense, you slacker/slouch/good-for-nothing? Go make my food quickly!). Here we could say Abbu in Urdu and Abba in Punjabi (meaning “father”), Ammi and Ammi (meaning “mother”), Taya, Tayee, Chacha, and Chachi (two ways of saying Aunt and Uncle); and if we wish to pick a word that exists in both Punjabi and English, we could pick school/sakul (though “madrasa” is probably more common); and if we wanted to see a word that was the same in English as it is in Swedish, we could use “telefon”; and if we wanted to say a word that is the same in Swedish as it is in Norwegian—well, heck, you could say “Jag kommer från Norge” in Swedish (“I come from Norway”), and all it would translate to once it crossed the border would be “Jeg kommer fra Norge.”

I don’t know which paper to get. I’m in the Out of Town News kiosk and I don’t know what to get. They’re all so expensive. I look at copies of Le Monde and El Pais, The Irish Times, and others, walking in a short semicircle, trying to avoid omnipresent tourists. There are no papers here in Catalan, Gaelic, or Creole. I look at the papers again.

In a follow-up email with Karolina Zawadzka, she wrote that she had “read a great interview with Michal Rusinek—he was a personal assistant of Wislawa Szymborska (you should have heard about her ;).) Rusinek is a polish scholar and writer, and a journalist asked him, in what he sets his hopes and he said LANGUAGE!”

I paid for my paper and left.

By Evan Fleischer // Phenakistoscope image by Eadweard Muybridge, ca. 1893. via Tumblr