Snapchat wants people to snap as many selfies as possible, but does it push them to do so at inappropriate times? A lawsuit filed against the company posits that Snapchat’s speed filter encourages reckless driving and causes accidents, and is launching a dialogue about technology’s role in vehicles.

The suit, filed in Spalding County, Georgia, is brought by Wentworth and Karen Maynard, a couple who had their car struck by an 18-year-old driver named Christal McGee. Wentworth Maynard was in the car at the time when McGee drove her father’s Mercedes into Maynard’s Mitsubishi Outlander at 113 miles per hour.

According to McGee, she was traveling at the high rate of speed on the Georgia highway, where the speed limit is 55, because she was “just trying to get the car to 100 miles per hour to post it on Snapchat.” She had been using the speed filter on the app, which overlays the rate of speed, in miles per hour, that a person is traveling.

The collision pushed Maynard’s vehicle into an embankment while McGee’s car was sent spinning into the opposite side of the road. McGee hit her head on the windshield, and she and her passengers were treated at at nearby hospital for cuts and bruises.

Maynard experienced a severe traumatic brain injury that required a five-week stay in the intensive care unit, during which he required the assistance of a breathing and feeding tube. He spent six additional weeks in the hospital for rehabilitation and, according to the lawsuit, requires the assistance of a wheelchair or walker and continues to experience difficulties with communication, memory loss, and depression.

The story is a tragic and obviously avoidable one. The question for the court is to what degree Snapchat is to blame. The Maynard’s legal team, led by attorney Michael L. Neff, argue that Snapchat—and specifically its filter that records rate of speed, leads to users partaking in reckless and irresponsible behavior behind the wheel.

They point to a 19-year-old in the United Kingdom who posted a snap traveling at 142mph. He killed another motorist in a crash while traveling at 80mph the next day. It’s worth noting, though, that there was no indication that he was using Snapchat at the time and he didn’t use the Snapchat speed filter to record his driving at 142mph; he just captured his speedometer with a Snapchat photo.

Maynard’s case also cites several similar instances—including cases involving public figures—where Snapchat is used to document dangerous behavior behind the wheel. They also suggest that Snapchat’s trophies system, which awards users for taking pictures with certain filters or in specific situations, promotes recklessness.

What isn’t clear is just how well this argument will hold up in front of a jury. It may be that Snapchat’s speed filter emboldens people to take photos at high rates of speed, but Snapchat has also actively attempted to discourage such behavior.

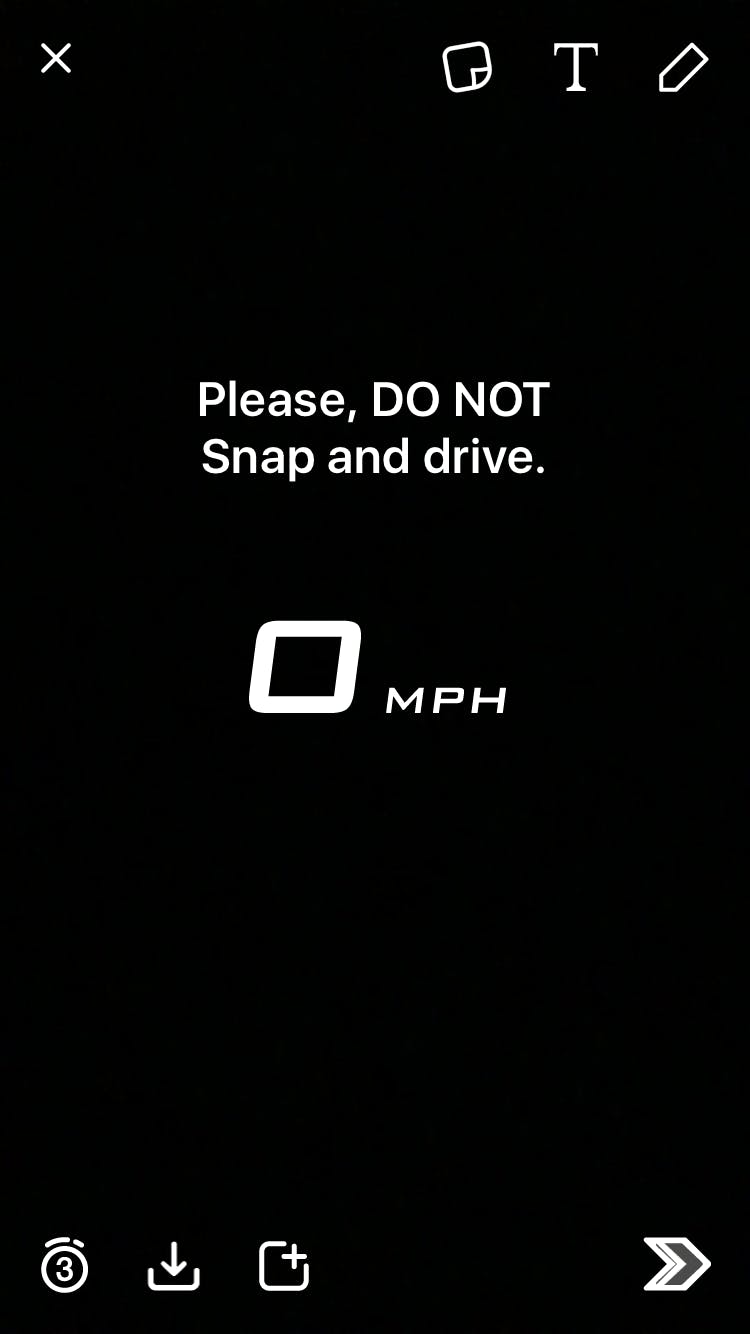

In a statement to the Daily Dot, a Snapchat spokesperson said, “No Snap is more important than someone’s safety. We actively discourage our community from using the speed filter while driving, including by displaying a ‘Do NOT Snap and Drive’ warning message in the app itself.”

That warning appears when a user attempts to use the speed filter, and though Snapchat could deactivate the filter at certain rates of speed, the app can’t differentiate between when a person is a driver—when using it would be dangerous—or a passenger.

Snapchat also includes a traffic safety policy in its Terms of Service that reads, “We also care about your safety while using our Services. So do not use our Services in a way that would distract you from obeying traffic or safety laws. And never put yourself or others in harm’s way just to capture a Snap.”

Snapchat’s trophies system does not include any reward for using the speed filter for any purpose, according to Snapchat and third-party trophy tracking site Snapchat Trophies.

The primary question at this point is if that all is enough to absolve Snapchat of its liability to ensure the safety of its users—and if more should be done by outside forces.

Joel Feldman, an attorney and the proprietor of the foundation End Distracted Driving, told the Daily Dot that in the Snapchat case, the question for a judge is whether Snapchat could have foreseen its filter being used in such a way.

“It’s not just what the manufacturer intended the product to be used for…it’s what’s foreseeable,” he said. “If someone misuses it, was it foreseeable?”

Snapchat maintains that the filter is not designed to be used in such a way, and can be safely used for other actions that involve speed, such as running, biking, or being in the passenger seat of a vehicle. But critics say the very existence of the filter may create an environment for misuses to occur.

While Feldman said he was “glad to hear” Snapchat offers warnings about driving safely, he noted the first thing any manufacturer should do is try to design out any risks that their product may contain. “If it’s not feasible to do so, the last resort is that you add a warning,” he explained.

Feldman pointed to instances in his law practice in which bars have been charged with creating an atmosphere that encourages drunk driving by offering cheap drink specials and large servings of alcohol at discounted prices. The case against Snapchat may take a similar shape to the so-called “dram shop laws” that are in place in many states which hold accountable establishments that sell alcoholic beverages to patrons who subsequently get into an accident due to being drunk or impaired.

Thus far, there is no precedent for an app or device manufacturer being held accountable for distracted driving, despite more than one in four car crashes being linked to cell phone use, according to the National Safety Council (NSC)—a figure that is believed by the NSC to be lower than the actual number due to under-reporting of phone-related accidents. There have been attempts to sue telecommunications providers, but have thus far been unsuccessful.

And it’s not just cell phones, either; it’s the litany of in-car distractions that can potentially take a driver’s attention off the road. Feldman, who lost his daughter to a distracted driver who was reaching for his GPS, said that she would be “just as dead as if he had been texting or Snapchatting.”

Distracted driving is spurred primarily by second screens—be the GPS, smartphone, or other—and have led to 3,300 deaths and 400,000 injuries a year in the United States, according to the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine. While laws have been implemented in many states in an effort to lessen or eliminate these tragic figures, the results have been mixed.

Feldman believes it isn’t just a matter of creating laws, but a more concerted effort to dismiss distractions and remained focused when behind the wheel. “With more and more technology, our society is going to have to figure out—and legally we’re going to have to figure out—what’s permissible and what’s not permissible,” he said.

Interestingly, the same arch of technological advancement that is leading to increased distractions—media systems, smartphone-connected screens, in-car Wi-Fi, etc.—should eventually lead to curb the harm of distracted drivers by replacing the driver entirely.

In the long-term, autonomous vehicles present a future in which humans won’t have their eyes pulled from the road because they won’t be the primary driver—the car itself will be. Driverless cars are still a long way from being road-ready in big enough numbers to take humans out of the equation—and for the time being, autonomous cars aren’t crash-proof, either.

Some studies even suggest that self-driving cars may cause even more issues for human drivers because people cant seem to stop crashing into computer-run vehicles. But, if the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers is correct in its prediction that 75 percent of cars on the roads in the world will be autonomous by 2040, then it presents significant opportunity for eliminating much of the human error responsible for accidents.

It’s difficult to regulate technology out of vehicles, especially as they are becoming more connected every year, and it’s not clear just how effective laws have been in eliminating distracted driving; studies have suggested that the only truly effective method is to entirely prevent device use in cars, as almost no amount of time looking at a screen is considered permissible.

For comparison’s sake, it’s worth looking at the effectiveness of laws for driving under the influence. States with particularly strict drunk driving laws don’t find much in terms of correlation to a decrease in drunk driving.

The biggest driving force behind the decrease in incidents with drunk drivers, according to Professor Adam Gerschowitz of William and Mary Law School, isn’t the harshness of the punishment but rather the likelihood that a person will face said punishment; in essence, it’s better to increase the chance that a person will be caught than to increase the punishment if they are caught. This theory plays out in the data, which shows that densely populated areas have seen a much larger decrease in drunk driving accidents than more rural areas.

One potential solution is to stop isolating drunk driving as its own infraction and instead broaden the offense to reckless driving of any kind, distracted driving included. Doing so would stigmatize distracted driving in the same way Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) has so successfully done with driving under the influence while also increasing the likelihood a person is stopped for any sort of careless behavior that puts others at risk.

Whether Snapchat becomes the catalyst for this type of reform remains to be seen. Regardless if the app is found to be partially or fully responsible for its users behaviors or not, it will may well spark a conversation about just how big a role technology should play in constraining the behaviors and actions it may well influence.