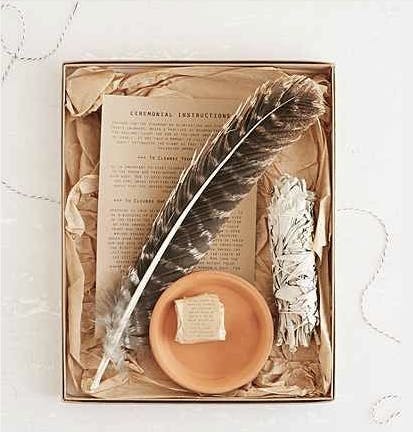

I never thought I’d see the day when an “energy-balancing smudge kit” would have a “product sku” number 34519397 and a “color code,” 012 and yet, until recently, it was featured on Urban Outfitters’ website. You can still find it on Pinterest.

The kit comes with its own “wild turkey smudging feather, stoneware smudging dish, candle and instructions.” Yes, instructions. It’s hard for me to imagine how they are written. I got my instructions from my relatives while being taught our traditional ceremonies passed down for generations in my family. These ceremonies were originally given to our Dakota/Lakota people by the Pte San Win (the White Buffalo Calf Woman), a sacred being who came to us and brought us the sacred pipe.

The Dakota don’t generally use turkey feathers in ceremony (although, some tribes do), but since the eagle feathers we do use are illegal for non-federally recognized tribal members to sell or possess, Urban Outfitters would not be able to sell them. The illegal sale of eagle feathers is punishable by up to two years in prison and a $250,000 fine.

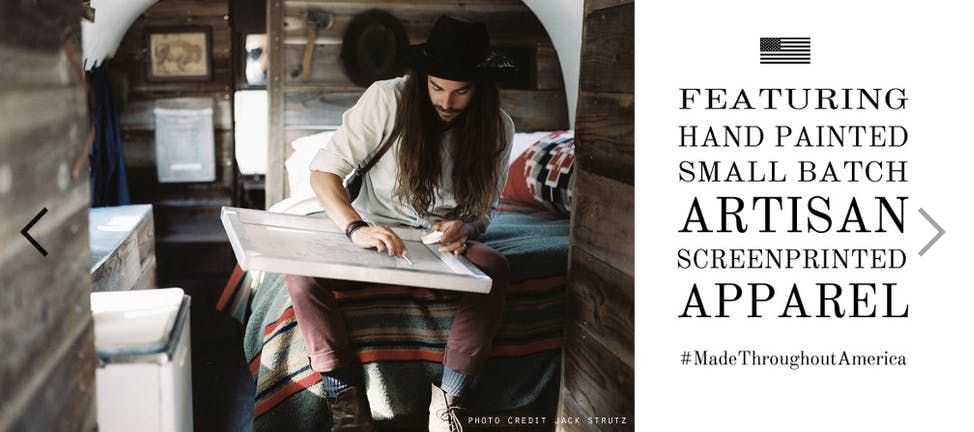

This “smudge kit” is manufactured by “The Local Branch” owned by Mackenzie Edgerton & Blaine Vossler, a traveling, artisanal, white hipster couple living in an Airstream who sells these kits to Urban Outfitters. The couple also advertises “Bison Beanies,” “handcrafted holsters for the modern pioneer,” and “artisan screen printed” tank tops that feature appropriated Native American designs. The Local Branch’s aesthetic is like a more millennial, festival-inspired Ralph Lauren with Americana heavily featured; they proudly display both an American flag and a bison skull (also sacred to the Dakota) in their Design Sponge-featured Airstream rustic renovation.

The company also sells a $146.00 “holster” on its website for carrying cell phones. This is ironic, of course, because most of us are familiar with them from gunfights in old-fashioned Westerns. But for Native people, both in actual history and in the movies, that same gun culture meant that those “pioneers,” as the couple markets themselves, signified death, total war, war crimes, and genocide. “Pioneer” is derived from a French word referring to “peons,” the disposable poor who were sent ahead of the regular military. Whether in the American West or elsewhere, the term has always been a reference for the dispossession of land and the truly free people who live on it.

They say that we were not Dakota until we began practicing these ceremonies—then we became Dakota. The ceremonies brought to us by Pte San Win represent the formalization of our sacred, life-sustaining relationship with the buffalo nation, the Tatanka Oyate. This relationship cannot be purchased, not even “artisanally,” and should not be sold by a corporate entity traded on Wall Street.

The Great Plains were once littered with the bodies of the buffalo people left to rot as part of a total war waged against Native Americans by the U.S. and its “pioneers.” Bison and Dakota people were shot by guns held in those holsters. The U.S. implicitly understood the intimate relationship our people had with those 25 million-plus buffalo that roamed the plains, and they destroyed them for it. By 1889, the numbers of the buffalo were just a few hundred and our people, or what was left of them, were forced into so-called “happy camps.” The fact that Edgerton and Vossler thought nothing of profiting off our ceremonies and our cultural heritage, even though they knew so little about history that they didn’t know it wasn’t OK—or that calling themselves “pioneers” was not ironic but actually true to form.

These ceremonies, like smudging, mean something to us. They mean a connection to our past of being a free people or person, an ikce wicasa as we say—and not a peasant or peon or pioneer. Being tatanka and not cattle means something.

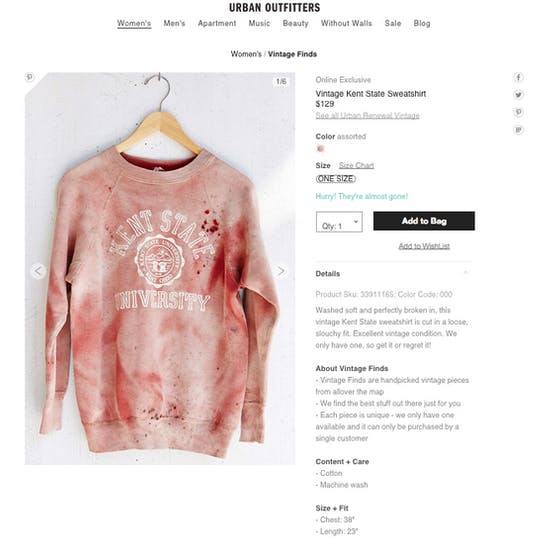

I am shocked that Urban Outfitters up to its cultural appropriation tactics again. My mom’s people, the Navajo Nation, are actually suing them in court for doing so, which they’re arguing amounts to a slew of trademark violations. In 2012, the Navajo Nation filed suit arguing that American Apparel’s clothing violates trademark standards established by “the federal Indian Arts and Crafts Act, which makes it illegal to sell arts or crafts in a way that falsely suggests they were produced by Native Americans,” as the Guardian reports. The original suit took issue with the retailer’s line of Navajo-themed underwear, complete with a flask, a particular affront to a group of people disproportionately affected by alcohol addiction.

But despite numerous culturally insensitive gaffes, Urban Outfitters is doing quite well: Sales are surging, and stocks up 12.5 percent. Meanwhile, CNN Money reported in March, “Last month, the company was criticized for selling a tapestry that many thought looked too much like a Nazi concentration camp uniform. That followed two ridiculously insensitive pieces of apparel last year: a Kent State sweatshirt that appeared to have blood splatter and bullet holes on it and a drunk Jesus T-shirt in honor of St. Patrick’s Day.”

For those interested in Native American clothing and culture, the solution is simple: Stop buying it from Urban Outfitters and their affiliated chains. Don’t support their bottom line. Instead, check out Nooksack artist Louie Gong’s site, Inspired Natives. The goal of this project is to promote the work of Native artists, the “Inspired Natives” of the title, rather than work that is simply inspired by their culture and steals from it. On his site, Gong notes that, on top of the cultural appropriation issues, the biggest problem with “‘Native-inspired’ goods on the market [is that they] ultimately squeeze out Native artists.”

I asked Gong what he thought of “The Local Branch” product line. “Culture and cultural art are like other types of resources,” he told me. “Regardless of how well-intentioned you might be, if you keep taking it without putting anything back into the environment that created it, you eventually destroy it. This is a lesson indigenous people have been trying to communicate for centuries. It’s ironic that the business people who are so eager to align with our values and the environment are still perpetuating a way of being that killed the buffalo and clear-cut the forests.”

Gong is right: We can’t change the past, but we can help change the future. This starts when we work to support the actual artists who represent Native cultures, as well as paying tribute to the rich and complicated behind these designs and ceremonies. It might look like just a bunch of paint to Urban Outfitters and The Local Branch, a way to look hip at an outdoor music festival, but to my people, “smudging” is much more—and that meaning should be fought for. In order to avoid reliving our own histories, it’s best to stop repeating their mistakes, while allowing multi-billion dollar businesses to profit off of them.

Jacqueline Keeler is a Navajo/Yankton Dakota Sioux writer living in Portland, Ore., and is a founder of EONM.org (Eradicating Offensive Native Mascotry). She has been published in Salon, Indian Country Today, and the Nation. Keeler is finishing her first novel “Leaving the Glittering World,” set in the shadow of the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington State during the discovery of Kennewick Man.

Photo via Brian Tomlinson/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)