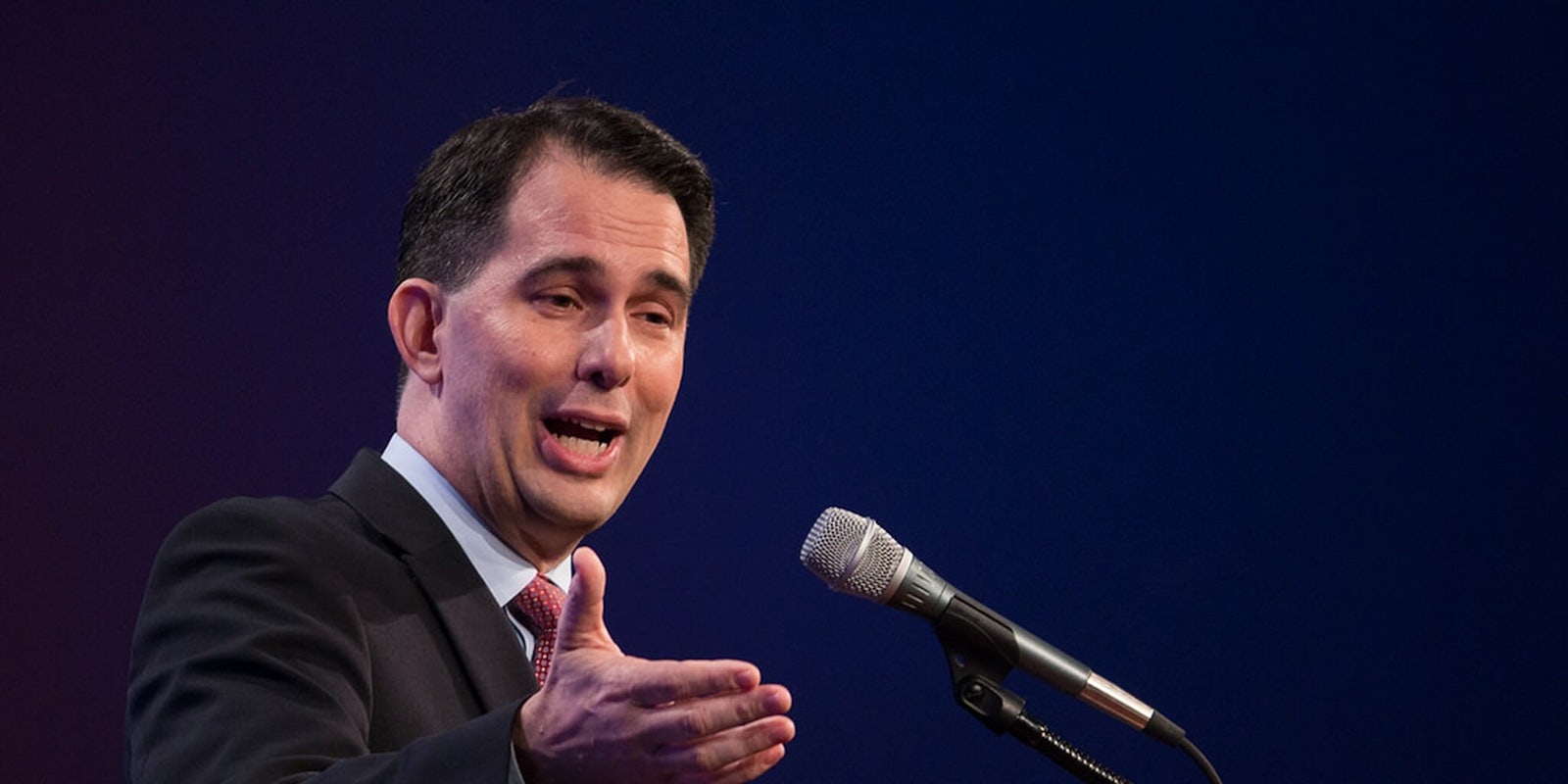

On Tuesday morning, Gov. Scott Walker (R-Wisc.) announced what many had widely speculated, following a nationwide drop in support: He is dropping out of the presidential race. Walker emphasized in a Facebook post that he hopes his withdrawal will encourage a more “positive” race. That’s a nice message, but optimism isn’t entirely the reason for his withdrawal: The presidential hopeful simply ran out of money.

According to the New York Times, “Walker was among the most successful fundraisers in his party, with a clutch of billionaires in his corner and tens of millions of dollars behind his presidential ambitions.” However, this didn’t allow his campaign to cover all of its expenses, as running for president is increasingly expensive. “Super PACs, Mr. Walker learned, cannot pay rent, phone bills, salaries, airfares or ballot access fees,” the Times’ Nicholas Confessore wrote.

As a result, despite being on pace to raise up to $40 million by the end of the year, Walker’s Super PAC was unable to keep his candidacy afloat.

This matters, especially in a presidential race that is estimated to amass record campaign donations—and spending—from candidates. Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and former Florida governor Jeb Bush are likely to shell out at least $2 billion on their bids for the White House, which is double the sum that President Obama and Mitt Romney’s campaigns racked up in 2012. For those who aren’t billion dollar candidates, it’s hard to compete.

That’s a nice message, but optimism isn’t entirely the reason for his withdrawal: The presidential hopeful simply ran out of money.

Former Texas governor Rick Perry also learned this lesson—after becoming the first Republican presidential candidate to drop out of the race. Although Super PACs like Opportunity and Freedom PAC had accumulated $13 million in order to gradually roll out a detailed campaign plan for Perry, it quickly found itself redirecting funds to Perry’s field operations in Iowa, after the candidate fell below fundraising expectations. When even that wasn’t enough to improve Perry’s fortunes and he withdrew from the race, the Super PACs were forced to refund the money to their donors.

As Yoni Appelbaum of the Atlantic points out, many observers assumed that Super PACs would fundamentally transform the dynamic of presidential elections by allowing wealthy benefactors to prop up their favorite candidates—even if they’d run out of money.

Subsequent events have revealed a couple of problems with this assumption. As already discussed, there are limits to what Super PAC money can pay for in a campaign. Whereas “hard money”—that is, funds acquired directly from individual donors up to the $2,700 limit—can be used for any legitimate campaign expenses, Super PAC funds can only pay for things like television ads.

Although the Perry and Walker campaigns apparently hoped they could use positive advertising to offset their lack of funds for field expenses, political realities quickly demonstrated that this was not the case.

In addition, because Super PACs are legally prohibited from working too closely with the campaigns they’re meant to help fund, candidates are in a catch-22 when it comes to staffing them: If they ask their savviest and most trusted advisers to helm these operations, they forfeit the services of their best talent. But if they don’t assign such individuals to take charge of their Super PACs, they run the risk that the organization might develop an independent streak—instead of serving their own interests.

For those who aren’t billion dollar candidates, it’s hard to compete.

As Molly Ball observed in The Atlantic, this proved particularly problematic for Walker, whose Super PAC was run by Keith Gilkes (who ran Walker’s 2010 campaign for governor and his 2012 recall effort) and Stephan Thompson (who ran the governor’s reelection campaign in 2014). Because Gilkes and Thompson were no longer able to communicate with Walker himself, the governor had to rely on a new slate of top advisers. The result was an embarrassingly mismanaged campaign replete with widely publicized gaffes that left his political brand in tatters.

There are two takeaways from this. The downfall of Perry and Walker demonstrates that—instead of Super PACs allowing the super-rich to even further game our political system–there are limits to how far a candidate can go without broader popular support. “There is something democratic about grass-roots, widespread money support,” explained former George W. Bush press secretary Ari Fleischer. “There is something anti-democratic about… propping up a candidate who can’t make it.”

At the same time, it says a great deal about our political system that Walker and Perry were so dependent on large sums of money in the first place. For one, it demonstrates that our election season is broken—increasingly long and bloated, with a high barrier both to entry and to remain in the race. Whereas underdog candidates used to regularly upset the race, it is now exceedingly rare for anyone who isn’t an early frontrunner to outlast the first few primary or caucus elections.

In the 2012 race, GOP candidate and former House Speaker Newt Gingrich didn’t peak until months into the race, while Sen. Rick Santorum (R-Penn.) wasn’t able to mount a real challenge to Romney—the assumed frontrunner—until that January. If that were the 2016 contest, neither of them would have lasted long enough to ever pose a threat.

Our election season is broken—increasingly long and bloated, with a high barrier both to entry and to remain in the race.

While presumptive nominees and candidates with built-in name recognition inevitably benefit from this system, it discriminates against lesser-known alternatives by denying them the capital they’d need to become competitive. If you start out out in last place, it means you’re likely to stay there.

If the odds are stacked against true outsiders—those who don’t have Donald Trump’s massive net worth or campaign war chest—the public is taking notice. According to a New York Times poll taken last June, 84 percent of Americans believe money has too much influence in politics. While 77 percent Americans additionally want to limit the amount that individuals and private groups can give, politicians like Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) support the public funding of elections. “The need for real campaign finance reform is not a progressive issue. It is not a conservative issue,“ Sanders has said. “It is an American issue.”

He’s right: This isn’t about polling numbers or whether you support Rick Perry or Scott Walker; it’s about the state of politics in 2015. A true democracy cannot exist if presidential candidates are being defeated by their checkbooks instead of at the ballot box.

Matt Rozsa is a Ph. D. student in American history at Lehigh University who specializes in national politics. As a political columnist, his editorials have been published on Salon, Mic, and MSNBC.

Photo via IPRIImages/Flickr (CC BY ND 2.0)