In August of this year, Ladar Levison shut down his email service, Lavabit, in an attempt to avoid complying with a US government request for his users’ emails. To defy the US government’s gag order and shut down his service took great courage, and I believe that Ladar deserves our support in his legal defense of that decision.

There is now an effort underway to restart the Lavabit project, however, which might be a good opportunity to take a critical look at the service itself. After all, how is it possible that a service which wasn’t supposed to have access to its users’ emails found itself in a position where it had no other option but to shut down in an attempt to avoid complying with a request for the contents of its users’ emails?

The Guarantee

This was the front page of Lavabit in July, the month before its shut down:

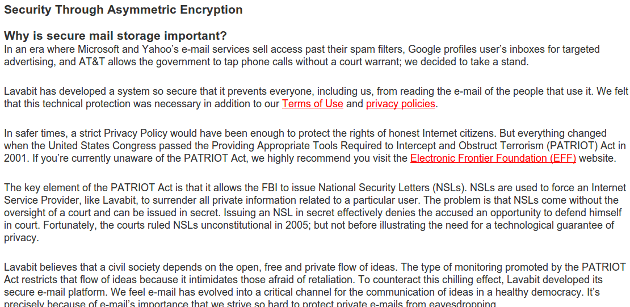

The front page proudly claims Lavabit is ”so secure that even our administrators can’t read your e-mail.” That sounds like exactly what one wants from an encrypted email provider, so let’s drill down and see what the details are on that “secure” link:

Again, this sounds awesome. They advocate that in today’s world, a service which merely promises to respect their users’ privacy with a policy statement isn’t enough, and that users should demand technical solutions which employ the use of cryptography to protect their privacy. This is the critical difference between a service that ”can’t read” and ”won’t read” your email, which was presumably the draw for many of Lavabit’s 40,000 users.

The Mechanics

So how did it actually work? And if, as they said, they weren’t capable of reading their users’ emails, how could they have been in a position to provide those plaintext emails to the US government?

Unfortunately, their primary security claim wasn’t actually true. As Ladar himself explained in this blog post, the system consisted of four basic steps:

- At account creation time, the user selected a login passphrase and transmitted it to the server.

- The server generated a keypair for that user, encrypted the private key with the login passphrase the user had selected, and stored it on the server.

- For every incoming email the user received, the server would encrypt it with the user’s public key, and store it on the server.

- When the user wanted to retrieve an email, they would transmit their password to the server, which would avert its eyes from the plaintext encryption password it had just received, use it to decrypt the private key (averting its eyes), use the private key to decrypt the email (again averting its eyes), and transmit the plaintext email to the user (averting its eyes one last time).

Unlike the design of most secure servers, which are ciphertext in and ciphertext out, this is the inverse: plaintext in and plaintext out. The server stores your password for authentication, uses that same password for an encryption key, and promises not to look at either the incoming plaintext, the password itself, or the outgoing plaintext.

The ciphertext, key, and password are all stored on the server using a mechanism that is solely within the server’s control and which the client has no ability to verify. There is no way to ever prove or disprove whether any encryption was ever happening at all, and whether it was or not makes little difference.

Measuring Up

A typical (unencrypted) email provider has three main adversaries:

- The operator, who has access to the server.

- An attacker who can get access to the server.

- An attacker who can intercept the communication to the server.

Despite the use of cryptography, Lavabit is also vulnerable to all three, just like a conventional (unencrypted) email service. The operator can at any time stop averting their eyes, an attacker who compromises the server can log the password a user transmits, and an attacker who can intercept communication to the server can obtain the password as well as the plaintext email.

Even though Lavabit’s security page went on at length about how, in the age of the PATRIOT act, users shouldn’t accept a Privacy Policy as enough to protect them, that is almost exactly what they implemented. The cryptography was nothing more than a lot of overhead and some shorthand for a promise not to peek. Even though they advertised that they ”can’t” read your email, what they meant was that they would choose not to.

Perhaps we’re just not reading between the lines, and all this handwaving was a ruse designed to trick the legal system (by claiming they were “unable” to respond to subpoenas), rather than a ruse designed to trick their users. That could have been a plausible experiment to try, but Hushmail had already tried the exact same experiment a decade earlier and met with the exact same fate.

It’s not clear whether the Lavabit crew consciously understood the system’s shortcomings and chose to misrepresent them, or if they really believed they had built something based on can’t rather than won’t. One way or the other, in the security world, a product that uses the language of cryptography to fundamentally misrepresent its capabilities is the basic definition of snake oil.

The Big Question

In the end, the US government requested Lavabit’s SSL key. One big question is why they didn’t just get a CA to make them their own.

Maybe they were just lazy and assumed that since Lavabit had previously complied with government subpoenas, they wouldn’t resist this one. The other possibility, however, is that the government was more interested in past emails than future emails. If the government wanted access to emails that might have already been deleted, their own SSL certificate wouldn’t help them.

We know that the US government stores large amounts of ciphertext traffic, and since Lavabit wasn’t preferring PFS SSL cipher suites, the government would have been able to go back and decrypt previous traffic with Lavabit’s SSL key.

When Lavabit did eventually provide the SSL key (albeit in really tiny font!), perhaps that’s exactly what the US government did, and any user who signed up thinking they were using some kind of special secure email was compromised.

The Quest for Secure Email

I think we should celebrate and support Ladar for making the hard choice that he did to at least speak out and let his users know they’d been compromised. However, I think we should simultaneously be extremely critical of the technical choices and false guarantees that put Ladar in that position. There is current an effort underway to release the Lavabit infrastructure under an open source license, which I worry will result in more of the same. Given its technical foundations, I wouldn’t advocate supporting the continuation of the Lavabit project.

Rather than funding Lavabit, if you’re interested in supporting a secure email project, I have two alternate recommendations:

- Mailpile. Despite what anyone tells you, end to end encrypted email is not possible in a webmail world. The first precondition for developing a usable and forward secure email protocol is a usable mail client, and I currently believe that Mailpile is our best shot at that.

- Leap Encrypted Access Project. This is a secure email project by people who fundamentally understand the challenges, the history, and the politics. They’ve been working on an incremental plan for developing a secure email system with some really smart people, and I think we’ll all benefit from their work.

Trevor Perrin has also been doing some excellent work on an asynchronous protocol for secure email, which I encourage everyone to take a look at and follow along.

This piece originally appeared on Moxie Marlinspike’s website, thoughtcrime.org, and is republished with permission.

Illustration by Jason Reed