Everyone loves a hero. The Internet, however, especially loves an anti-hero.

The most recent in the long list of anti-heroes embraced by the Internet is Christopher Dorner. Within that anti-hero worship is evidence of the very nature and foundations of the Internet, as well as evidence of its biggest challenges today.

Dorner, as we all now know, is a former LAPD officer who went on a revenge-inspired killing spree and is now presumed dead after a five-hour standoff with police. His revenge spree—in which he released a 14-page manifesto complete with a hit list, and murdered the lawyer who represented him in his dismissal hearing and her husband—feels like something out of a movie. The manhunt unleashed on Dorner is equally cinematic, including police shootings of three innocent bystanders and the first high-profile use of domestic drones.

The Internet has reacted dramatically, of course, and much of that is in sympathy with Dorner.

Some of this is the kind of gallows humor that appropriately satirizes the catastrophic bumbling, not to say active carelessness, of the LAPD, like the T-shirts emblazoned with “Don’t Shoot I Am Not Chris Dorner” that are all the rage. Less light-hearted but no less deserved are the innumerable questions appearing on Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit questioning the LAPD. I do not know if the actions of the LAPD are defensible, but I’d guess it’s safe to say that when law enforcement racks up a body count of innocents similar to the victims of the criminal they are pursuing, then something is wrong.

Some of this is the kind of gallows humor that appropriately satirizes the catastrophic bumbling, not to say active carelessness, of the LAPD, like the T-shirts emblazoned with “Don’t Shoot I Am Not Chris Dorner” that are all the rage. Less light-hearted but no less deserved are the innumerable questions appearing on Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit questioning the LAPD. I do not know if the actions of the LAPD are defensible, but I’d guess it’s safe to say that when law enforcement racks up a body count of innocents similar to the victims of the criminal they are pursuing, then something is wrong.

But a lot of the Internet reaction is of a different tone, lionizing Chris Dorner as a crusader of the truth. One popular meme depicts Dorner as “chocolate Rambo”—a slightly snide term, yes, but one that still carries a sense of backhanded approval. A White House petition urging the government to investigate Dorner’s accusations has almost 3,000 signatures. Anonymous has acted in support of Dorner, taking down the LAPD’s website (or at least claiming to). There’s a range of Facebook pages supporting Dorner; “We are all Chris Dorner” has over 2,000 likes.

***

Dorner is embraced by the Internet because he is both a product of it and a natural fit for its fringe culture.

First off, Dorner wrote a manifesto. Of course manifestos are hardly unique to the Internet, but the Internet really does love a manifesto. I sometimes wonder if Anonymous exists simply to give people reasons to write manifestos. Dorner’s manifesto even specifically mentions Anonymous, saying, “you are hated, vilified, and considered an enemy of the state. I personally view you as a culture and a necessity that brings truth to a cloaked world. Forge ahead!”

He follows his statement on Anonymous with, “Charlie Sheen, you’re effin awesome.” Presumably he’s referring to Sheen’s Twitter antics (#winning), but he doesn’t specify. The manifesto rambles all over popular culture, with Internet fixations weaved throughout his disjointed narrative—from TV and news obsessions to the Chick Fil-A debacle and George Zimmerman’s attempts to rehabilitate his own reputation, Zimmerman himself, of course, being something of a hero to certain parts of the Internet.

***

The adulation of people like Zimmerman and Dorner is partially a result of the large numbers and free publishing the Internet afford. While surely every human on earth is against something like the needless killing of children, the truth is nothing is 100 percent. I read once that 95 percent of Kurds would have voted against Saddam Hussein if they’d been allowed to vote. That means that 5 percent of them would have voted for him. Even though he gassed them.

With so many people active online, some percentage of those people are always going to be on the less popular side of any event, even something like the killing of Trayvon Martin. Because of the freedom of the Internet, we’re all going to hear about it. In other words, we get to see and hear the margin of error.

That’s one part of why we see anti-hero worship like this on the Internet. But there’s more to it than that. Sympathy for the fringe is baked into the Internet’s fiber of being.

In the beginning, when the it was nothing but a few Usenet newsgroups, the Internet was populated by academics, hippie programmers, and conspiracy theorists. It was born of counter-culture. Today, even as it is becoming the culture, it retains that foundation.

4Chan and Reddit often seem like direct descendants of that pre-World Wide Web era, but new kinds of fringes find their home on the Internet every day. Marginalized individuals from bronies to fanfic writers find safety and community online. And they naturally feel an affinity for anyone else who is marginalized, whether that marginalization is for good cause or not.

***

What I love about the Internet is that it makes us each realize that we are all fringe—and we are not alone. Whatever your fandom, whether it’s OneDirection or classic cars or cute kittens: you are weird and you are not alone.

In a way, we’re all anti-heroes online. Every member of the worldwide Internet fringe, and we are all indeed marginalized, even beyond the large numbers and the traditional counter-culture of the Internet.

We are all marginalized because if you are an Internet user, you are, according to the government, almost certainly a criminal.

I am referring to End User License Agreements (EULAs)—those huge screens of text that you agree to without reading when you sign up for Facebook, Twitter, or most other Web services.

In most instances, if you violate an agreement with a company or individual, you simply have a civil breach of contract with the other party. In the case of EULAs, it is a federal crime.

Aaron Swartz discovered this fact when he downloaded academic articles from JSTOR to post them online. He broke JSTOR’s EULA in doing so, but JSTOR, recognizing that he was a young guy with decent (if problematic for an information economy) intentions, did not want to prosecute him. The federal government, however, didn’t care what JSTOR wanted, and since it is a felony to break a EULA, they prosecuted him without JSTOR’s blessing.

Since EULAs are exquisitely detailed and restrictive in order to protect the service provider against every conceivable misuse, I guarantee that you have broken one at some point. In other words, you are a criminal. We are all outlaws.

It is deeply misguided to support a vigilante—but when we are all outlaws, where is justice?

The law making EULA violations a federal crime was written with the early fringe hackers of the ’80s in mind. It did not anticipate that a quarter of a century later, we would all be part of that fringe.

The problem with CISPA, SOPA, the six-strikes policy, or ACTA is that each is an instance of the powers that be treating normal Internet behavior as criminal activity; normal users as a fringe that can be safely ignored.

When we are all outlaws, laws and governments become no more legitimate than vigilantes, and vigilantes appear as heros. Only when held up against the backdrop of true justice are vigilantes like Dorner revealed for what they really are: misguided souls unleashing brutal and unnecessary pain onto the world. When the sickness of the system around the Internet is healed, supporters of people like Dorner will become simply be nothing more than a margin of error.

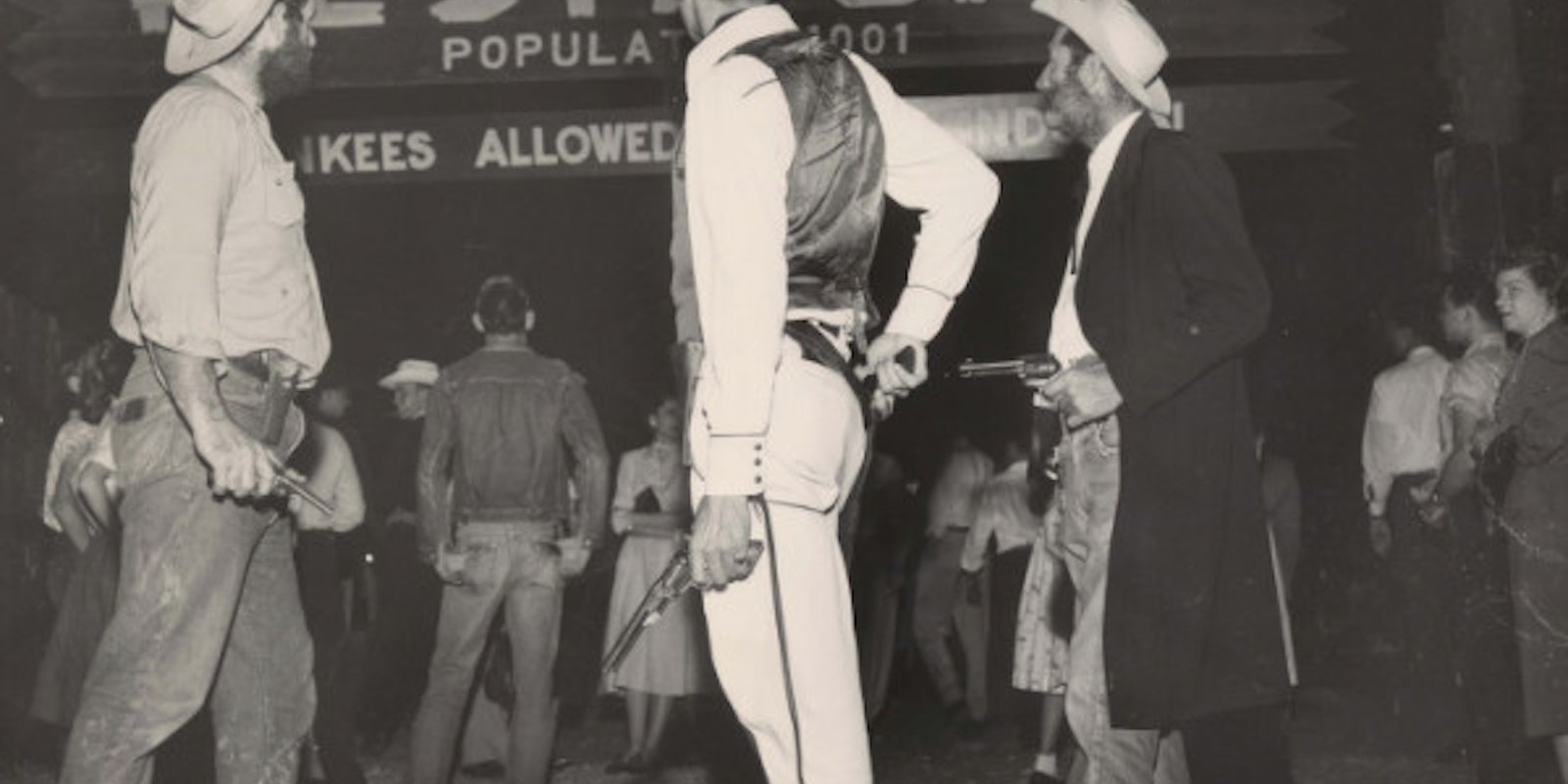

Photo by D Services