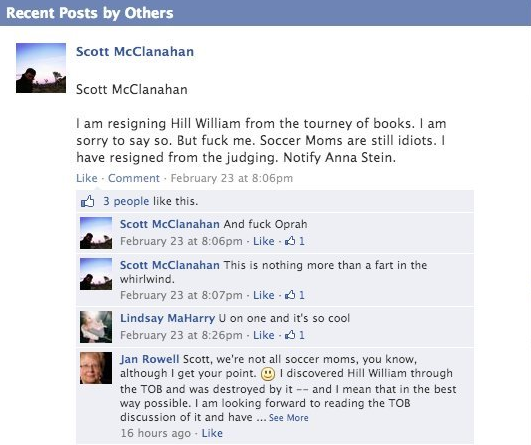

Months after the Morning News announced its bracket for the 2014 Tournament of Books but just days before his Appalachian novel Hill William was slated to square off against faux-Victorian tome and Man Booker Prize-winner The Luminaries in an opening round, author Scott McClanahan decided to stir up some trouble.

He trolled the tournament in a series of derogatory Facebook comments—and raised serious questions about the state of “Alt Lit” in the process.

“I just thought it was funny and absurd,” McClanahan told the Daily Dot in an email, when asked about his Facebook comments of Feb. 23—an outburst so minor it could easily have gone unnoticed by all but those who were in on the joke. Readers these days, however, are as likely to vet a writer’s social media presence as they are the work itself, so McClanahan’s insulting “resignation,” carefully styled to appear tossed-off, was widely taken at face value.

Getting the name of the contest wrong, maligning a broad and ill-defined group like “soccer moms,” and oddly referring to his agent—all were clear indications that McClanahan hoped to sow maximum confusion and outrage in the Tournament of Books’ devoted commentariat, a group whose intensity of feeling and opinion is heightened by the shortness of their time together each year. The status update appeared in the comment section for the tournament’s pre-bracket playoff round, and the first few dozen remarks there concerned McClanahan and Hill William, despite the post itself being a matchup between two other, unrelated titles. Thread: hijacked.

“Sometimes you have to act like a total ass to break through the boredom of these things,” McClanahan told me later on. “I was laughing when I did it and laughing when I saw the LA Times article and I’m still laughing … When did the LA Times start getting their news from the Internet? That’s what I want to know. No wonder newspapers are dying.”

Indeed, a former Tournament of Books judge wrote a piece for the Times that inflated the squabble into a bona fide literary scandal, casting McClanahan as an “indie” author attempting, without success, to disrupt a decade-long tradition. Although he wasn’t quoted, the organizers were; they said Hill William would stay in contention.

Part of their unruffled response has to do with the Tournament of Books’ reputation as a competition both eclectically egalitarian and decidedly arbitrary; it celebrates the subjectivity of taste with head-to-head comparisons readers wouldn’t otherwise make, and most of the time, that means there’s a token “indie” or Young Adult or genre work in the mix. (Full disclosure: My obscure, small-press novel Ivyland was trounced in the 2013 bracket by the bestselling Gone Girl—which should give you an idea of the unusual matchups produced by this system.) Also, it was too late for McClanahan to drop out, as the judge’s first-round decisions had been filed weeks before.

Regardless, nobody expected Hill William to trump Eleanor Catton’s lavishly praised The Luminaries, a 900-page prestige blockbuster. And then, in a review published March 6, judge Rachel Fershleiser—who happens to be head of publishing outreach at Tumblr, itself responsible for some blogs-to-indie-book-deals—did exactly that, expressing dissatisfaction with both books and ultimately favoring McClanahan’s, as it felt more “alive.” Even though Fershleiser had written this well in advance of the nasty Facebook post, that move didn’t go over well:

Once again, it appeared that everyone was playing their role: The same small handful of commenters were freaking out to the point of developing conspiracy theories; the Morning News color commentators maintained a clear-eyed detachment (“An author doesn’t get to choose his critics, and as it happens, he got a favorable one today,” one said of his cryptic resignation); Catton probably ignored the whole thing—no doubt still sheltering from the fallout that accompanied her astute observations about industry sexism—and the emphatically impartial Fershleiser declined to speak on the record about the dust-up, having said her piece already.

Meanwhile, McClanahan was also playing to type, continuing to crack wise in the tradition of Web-based Alt Lit institutions like HTMLGIANT and Muumuu House. On a reading tour with members of that crew, he said, he had posted on Facebook “that Subway was sponsoring our tour and that the first 20 people would get free Subway sandwiches. There was a guy who showed up in Columbus and was actually wanting his free sandwich. He was pissed we just made up the Subway sponsorship.” Much of the Alt Lit world concerns these games of irony and intention. The losers are those who fail to realize some tongues never leave the cheek.

As for his Tournament of Books win, McClanahan was suitably mock-humble.

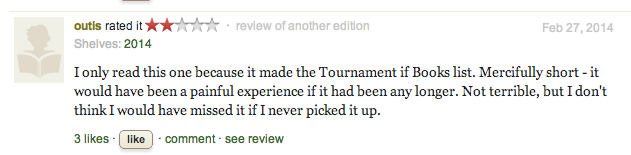

“I think The Luminaries was robbed,” he said. “I demand a recount. I’m ready to be eliminated.” Soon enough, he was, overtaken by Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being, and the whole half-controversy faded with a whimper. “I imagine McClanahan probably couldn’t handle being an insider,” wrote Morning News commentator John Warner, reinforcing the notion that the Tournament of Books, though it began as an offbeat forum for highly abstracted literary arguments, is now somehow representative of establishment or mainstream fiction, or as McClanahan might have it, a dumbed-down book club for the Internet. When I asked about his impressions of the participants, he was blunt.

“It looks to me like the comments are usually more interested in talking about Little Women or whether or not a novel ‘earns out’ or sold for 2 million dollars or fits into some small definition of what a novel should be. It seems like there is a lot of talk about the length of a book and a ‘contract with the reader’ or whether or not the reader finished the book. Of course, comment sections always make me think of Winston Churchill. He said the best argument against democracy was to walk down the street and talk to any five random people. I think this applies to most book culture as well.

“I only want to apologize to soccer, not moms,” he continued. “I could have said dentists, or chiropractors, and it would have meant the same thing. The problem for readers like this is that they read for edification rather than salvation.”

Suddenly, this no longer sounded like a joke, or a ploy to sell copies of Hill William, which is how many observers characterized McClanahan’s first broadside:

“[M]ost book things now (with a few exceptions) are just built around nice, safe books written for nice and safe book club readers. These are usually the books you see on display at Barnes and Noble. These Internet writers are like literary terrorists to me. They’re training as we speak. They’re getting ready to invade. They’re building an army.”

That’s hyperbole, but it indicates a genuine fear behind McClanahan’s façade of casual antagonism. “I just wanted to make sure Hill William got noticed that first week, and it obviously worked,” he said, and yet his attack comes from a place of philosophical angst, not mere boredom, cynicism, or cruelty. Perhaps this is the hellish bargain the Alt Lit writers—those poker-faced, Gchat-addicted, post-meaning millennials—have struck: Even when you’re dead serious, it looks like trolling, and they may not even acknowledge the difference themselves.

All of which feeds into a larger neuroticism that comes with discussions of art, especially online. Not only are we expected to stake out our camps of aesthetic opposition, we must do so through the filters of handcrafted Internet personae. In a sense, everything that came out of McClanahan’s dig was predetermined and pointless, the exact sequence of events he envisioned when he started typing it. I realized, the other day, when I came home to find a package containing Hill William in my mailbox, that I too had behaved as if programmed. Amused by the original incident, I thought to reward McClanahan with my money and further attention.

And to think they said that print was dead.

Correction: McClanahan did not invent a person named Anna Stein. That was a rather bizarre reference to his own agent. This article has also been updated to clarify that it was a former Tournament of Books judge who wrote the Los Angeles Times piece.

Photo via Scott McClanahan