This story is part of a series of features, The Future of Ride-Hailing. The project is intended to show how the taxicab industry, with varying degrees of success, is pushing back against the existential threat posed by the rise of ride-hailing services like Lyft and Uber.

It’s election day in Austin, Texas, and the campaign that funneled more than $8 million to secure the future of Uber and Lyft in the city didn’t bother to throw an official party to watch results.

An afternoon text from Ridesharing Works for Austin Deputy Outreach Director Huey Rey Fischer reads like resigned contempt for the process. “I’m tired of the pettiness of the politics in this town. It’s a real turnoff for young people,” he writes.

Ridesharing Works is the political action committee funded by ride-hailing leaders Uber and Lyft. In the past few weeks, it’s sent no less than 14 mailers to my South Austin address about Proposition 1, to pair with text messages and near-daily phone calls. I’ve even been offered a free ride to my polling location.

You can't say that @Uber and @lyft aren't trying. pic.twitter.com/72yYZR889Q

— Ramón Ramirez (@AThousandGrams) May 7, 2016

The ballot measure the PAC is jostling for has a confusing history with dense language. It’s a 60-word question:

Shall the City Code be amended to repeal City Ordinance No. 20151217-075 relating to Transportation Network Companies; and replace with an ordinance that would repeal and prohibit required fingerprinting, repeal the requirement to identify the vehicle with a distinctive emblem, repeal the prohibition against loading and unloading passengers in a travel lane, and require other regulations for Transportation Network Companies?

The gist is that a “yes” vote allows the ride-hailing apps to continue operating without three tiers of municipal regulation. A “no” endorses the ordinance the city passed in December, requiring, among other things, fingerprint-based background checks on all drivers.

Uber and Lyft pivoted on message several times with hopes of landing one that resonated. They settled on a bottom line: Both companies promised to cease operations in the state capital if Prop. 1 failed, a decision that would result in a lot of loss of jobs, opportunities, and convenience.

Now hope is beginning to dwindle for them. East-side bar Lustre Pearl is hosting about 30 Lyft drivers at an unofficial campaign gathering. Some huddle around a phone that’s livestreaming the results from NPR affiliate KUT: More than 55 percent of the public just voted no.

Come Monday morning, Lyft and Uber will be gone. A few drivers at the watering hole talk about staying off the roads tonight—let the city deal with what it just did, they say.

Depending on which faction of Austinites you side with, what voters did either set back the city’s technology sector and reputation for innovation while creating a public transportation crisis, or a plucky, vocal group of liberals stood up to corporate bullying.

Conservative Austin City Council member Don Zimmerman—tonight wearing white pants, a white shirt, black tie, and a gentlemanly straw hat—is livid.

“You pass all these rotten, useless ordinances against people and rules against people—now they can’t afford to do business, and they leave,” Zimmerman tells my Daily Dot colleague. “We’re the city of over-regulation controlled by the nanny council. We don’t have a city council, we have a nanny council.”

A Lyft driver I’ve recently met texts me his mixed feelings about the contentious, precedent-establishing election—one that often felt like a vote for the future of the ride-hailing industry.

“The amount of txts i have been getting from uber trying to solicit my vote is shameless On their behalf. On the other hand i don’t really feel like it is good legislation on behalf of the city council.”

Back at Lustre Pearl, a millennial-aged Lyft employee addresses his company’s flock of crestfallen contract laborers: “You guys are one of the most incredible Lyft communities of drivers I’ve ever met,” he says, introducing campaign organizer Nicole Redler. “You bet your ass this is going to be her first project is making sure that it gets back here ASAP.”

Redler thanks those gathered and is overcome with tears. Her cause could not have been helped by the fact that Ridesharing Works didn’t begin its campaign until April 3 with an optimism-tinged party at smoked meat haven, La Barbecue.

Drivers from surrounding suburbs—Lakeway, Round Rock, Cedar Park—ask about geo-fencing outside of city limits. Maybe they can keep working in the suburbs.

“I don’t have that answer,” the Lyft employee says. “Is that what you guys want?”

“We want to drive.”

Clear eyes, young hearts

A week before the May 7 election, Huey Rey Fischer was feeling good. The deputy outreach director for Ridesharing Works for Austin is in turbo mode, scrambling about campus to secure endorsements from student government.

We’re in Caffé Medici, a college coffeeshop. Fischer is thin, wears dark-framed glasses, and was drinking a mineral water to curb his sweating. He’s a recent graduate of the University of Texas, using this window between law school to dive into a campaign he claims to deeply believe in.

Fischer identifies as a progressive Democrat, and in March lost a race for state representative. He’s the openly gay son of a once-undocumented woman from Mexico, and he’s worked on more than 12 campaigns across Texas and as a legislative aide focused on environmental policies, according to his website. He’s not your usual Uber spokesman, then: that pro-business, Silicon Valley type who speaks in TED talk superlatives.

“They’ve called me a sellout. They’ve called me neoliberal scum. They’ve called me a corporate shill spokesperson,” Fischer said.

In December, the Austin City Council passed an ordinance requiring transportation network companies (TNCs) to conduct fingerprint-based background checks on drivers. Despite measures aimed to negotiate, facilitate, and incentivize this process, like Mayor Steve Adler’s Thumbs Up! program, Ridesharing Works petitioned more than 65,000 citizens to overturn the law. The Austin city clerk certified the petition, and it forced the Prop. 1 election.

Fischer thought it would take making it a generational issue to win.

“Both sides haven’t been very honest,” Fischer said. “Yeah, Uber has been heavy-handed in its tactics, that’s lousy. But putting all of the politics aside I care about how this will directly impact the quality of life for young people and students. … The older folks in this community who are voting against Uber because they hate Uber but they’ve never used Uber or Lyft before because they don’t need Uber and Lyft, they’ll carry on fine. But I’m going to see DWIs increase again. I’m going to see my friends putting themselves in riskier situations, and that’s just unacceptable.”

Fischer proudly points to the fact that when he debated former Council Member Laura Morrison in mid-April, she copped to never using Uber or Lyft: “Yet she spent three years arguing about it.”

He says Austin City Council often ignores student interests and points to noise ordinances near campus or last year’s clash over stealth dorms. He’s upset that these rulings are passed down without student input. “We end up getting screwed over in the process and that’s not fair,” Fischer said.

“It’s something we depend on. It’s something we trust,” he says about ride-hailing. “We understand what it’s like to just get into a car with a stranger because we trust that they went through a background check. It’s a service that we’re just comfortable with just like young people are comfortable using Tinder to go on dates.”

To help hammer home the message, Friday Night Lights actor Taylor Kitsch was brought to campus as a paid spokesman. Kitsch posed for photos with students during early voting in front of a “vote for prop 1” backdrop.

Despite the war chest, a Democratic party leader told me that Ridesharing Works waited far too long to get into the race. A week out from the election, Fischer thought he had the student vote. To pull this off, affection for ride-hailing—where undergrads make extra cash and get a ride to the airport from their phones—needed to be the prevailing narrative.

Fingerprinting and finger-pointing

At its most bare bones, Prop. 1 positions a 2014 ordinance adopted by the city against December’s move toward fingerprinting, and it’s pitted prominent members of the community against one another.

Former Mayor Lee Leffingwell, a paid Ridesharing Works consultant, clashed publicly with his Democratic successor, after penning a Ridesharing Works Facebook post: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” it read.

“It’s broken,” Council Member Ann Kitchen countered to the Daily Dot on the phone. Mayor Pro Tem Kathie Tovo added, “Having been on the council during the time when we had that 2014 policy discussion I disagree. That was intended to be an interim ordinance.”

At the time, Tovo says Uber and Lyft were operating illegally in Austin. The city pushed toward fingerprinting then, to no avail.

“At every step of the way, almost every time, there was an amendment introduced. My colleagues would invite an Uber spokesperson or a Lyft spokesperson up to provide comment and if they didn’t like the provision it was pretty well doomed,” Tovo said. “Uber and Lyft had a very strong hand in writing the 2014 ordinance.”

It was one Tovo supported, she says, because “we all understood that there would be a permanent ordinance coming behind it, which is what this council adopted in 2015.”

The ride-hailing supporters maintain that Lyft and Uber’s background checks are fine: They require submitting a driver’s license, vehicle registration, address, banking information; it’s a process that Fischer says goes through all 50 states, checks sex offender registries, and the terrorism watch list. Critics contend that’s not enough: Background checks only go back seven years. Prosecutors from a recent California lawsuit found that Uber drivers in San Francisco and Los Angeles, for example, had prior convictions for second-degree murder, kidnapping, and assault that went unnoticed.

“Up until a month ago the fingerprinting-based background check that the city uses for taxicab companies only looked at Texas, so it wasn’t even fully comprehensive and they only made it national once they realized that everything was being scrutinized in this election,” Fischer added.

Fischer’s chief gripe is about fingerprinting.

“Fingerprinting is discriminatory. By only looking at arrests and not final convictions, that poses a problem to over-policed communities,” Fischer says. “You don’t support discriminatory policies and say we’ll tackle it down the road. You either have a solution or you find an alternative, and the alternative is the background checks from Uber.”

It helps that Uber and Lyft’s in-house checks make business easier. The campaign says that the added, city-forced step will mean less drivers on the road, longer wait times, and a needless bureaucratic impediment. It says this step is an inefficient deal-breaker to operating in town.

“I just disagree,” Tovo said. “We have the DPS, FBI, our own Austin police chief who have all said fingerprint background checks are the only way to assure that the person you’re running a criminal background check on is actually the right person.”

Tovo says she doesn’t find Uber’s safety procedures to be “sufficient.” As for the notion of fingerprinting as targeting minority communities, she counters by noting that there is an opportunity in the process for an individual to provide follow-up information to the transportation staff and, for instance, note that a case was dismissed.

“We can’t prevent every violent crime from happening in this kind of vehicle for hire, certainly,” Tovo said, “but I think we have an obligation as a municipality to adopt the best practice safety measures.”

A tense 48 hours

Election day is, of course, a loss for Uber and Lyft. The city ultimately shoots down Prop. 1 down by more than 10,000 votes. Even the local endorsements are one-sided.

Mmmhmmm. #VoteAgainstProp1 #TNC #atx #ATXCouncil #Uber #Lyft pic.twitter.com/LnDHOWB93i

— Bobby Levinski (@BobbyLevinski) April 21, 2016

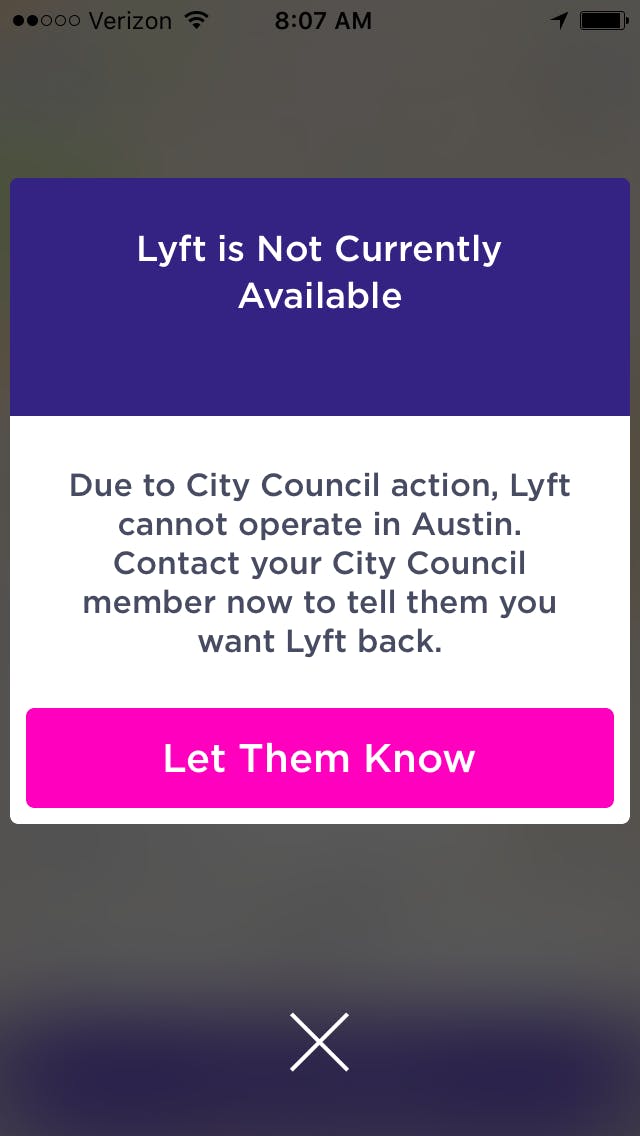

Monday morning, my apps go dark as promised. Lyft at 5am local time, Uber at 8am.

Uber and Lyft were done no favors by recent headlines: Alleged sexual harassment from an Uber driver in Boston; consumer protection lawsuits in San Francisco; most alarmingly, an Uber driver in Michigan allegedly killed six people in March.

In Austin, a Lyft driver was arrested under suspicion of DUI just before South by Southwest in March. On May 4, Uber was hit with a class-action lawsuit over its blitz of campaign texts to voters, while Lyft was hit with a million-dollar lawsuit after a motorcyclist died on April 23 from allegedly swerving to avoid a driver unloading passengers in the wrong lane. During election week the Austin Police Department showed that Uber and Lyft haven’t decreased drunk driving numbers by 23 percent as claimed—it’s actually 12 percent.

“Uber’s thought was that they could turn out all these different voters, these new voters who used and cared about the service,” Travis County Democratic Party Communications Director Joe Deshotel told the Daily Dot. “They can’t really question the validity of the vote, given that they outspent us 80-to-1.”

For their part, Uber and Lyft spokespersons expressed their disappointment with the results in statements emailed to the Daily Dot. From Lyft:

Unfortunately thousands of people who drive with ridesharing companies to earn much needed income will now have to find another way to make ends meet. Thousands more of our citizens and visitors from around the world will soon have one less option to get around town safely. … The benefits of ridesharing are clear: reduced drunk driving and economic opportunity. And we won’t stop fighting to bring it back.

And Uber:

Disappointment does not begin to describe how we feel about shutting down operations in Austin. For the past two years, drivers and riders made ridesharing work in this great city. We’re incredibly grateful. … We hope the City Council will reconsider their ordinance so we can work together to make the streets of Austin a safer place for everyone.

In the immediate aftermath of Saturday’s result, alternative ride-hailing app Get Me reportedly emailed 500 prospective drivers—and forgot to BCC everyone, exposing drivers’ personal email aliases. The Dallas-based app agreed to comply with the fingerprint checks, but it doesn’t appear to have the infrastructure to handle the uptick in business.

This fight won’t be over anytime soon, however. As the Atlantic’s Citylab blog notes: “Conservative state lawmakers have already signaled an interest in big-footing local government on ride-hailing regulations.” State Sen. Charles Schwertner (R-Georgetown), who chairs the Senate Committee on Health and Human Services, has vowed to craft state legislation that would overrule the Austin City Council.

Mass protests in favor of ride-hailing are on the books this month, too. Austin’s startup leaders and dissenting technocrats have taken to Twitter to air grievances:

Next time I'm raising money in Silicon Valley I'll have to answer "why is Austin so backwards?" Uphill battle already. Even worse now #Prop1

— Evan Baehr (@evanbaehr) May 8, 2016

If you fear riding with @Uber/@Lyft, just don't use them. Don't pass restrictions that increase costs or prevent me from using them. #Prop1

— Wesblog (@wesblog) May 8, 2016

https://twitter.com/liz_anne/status/729288179400876032

Liberalism has consequences–ATX always claims to be progressive–instead it voted for the past on Prop 1–Gov't won and the people lost

— George P. Bush (@georgepbush) May 8, 2016

Deshotel, the Travis County Democratic Party communications director, hopes both Mayor Adler and the TNCs can begin rebuilding soon after a “cool-off period.” Adler seems amenable to hashing it out, but he doesn’t appear to be holding his breath. As he told the Daily Dot Saturday night, “Frankly, I think we were innovating a little too quickly for Uber and Lyft. They’re big companies and sometimes they’re not quite as nimble as maybe you’d like, and now I think this might give us as a chance for all of us to catch up with each other.”

The problem is Deshotel says that the city now feels it has a mandate for fingerprinting, when in his opinion voters mostly felt cornered by Uber and Lyft. “At the end they’re just like ‘God fuck this company,’” he says.

While the dust settles, the fact remains that $8 million in influence just went into a failed campaign. How did Uber and Lyft fumble at the goal-line?

“By creating an astroturf campaign and not realizing that basically it takes more than algorithms to create a relationship with the voters,” Deshotel said. Or perhaps, more simply: “They thought they could just cut a check to the people that they needed and then harass people.”

Additional reporting by Samantha Grasso.