There are plenty of things on the Internet children should be sheltered from. Just like in real life, the Internet can be an odd, sometimes dangerous place, and parents often don’t feel comfortable letting their offspring roam the Web.

To alleviate parent’s Internet fears, Google launched the YouTube Kids app for Android and iOS that lets kids browse through and watch videos that are age-appropriate. It’s the company’s first step in an effort to make kid-friendly Google products, which will also include Search and Chrome for the 12-and-under set.

Vine, the Twitter-owned video-sharing application, also launched a standalone application for kids that features six-second videos appropriate for young children, accompanied by cartoon characters the company created.

Building apps for the kiddos isn’t a new idea. App companies have all sorts of musical, colorful, and educational toys for tech-minded tots, and the concept of taking popular apps and rebuilding them for kids makes a lot of sense. More users, fewer complaints (in theory, at least). Kuddle, for instance, markets itself as the Instagram for kids. And Amazon’s Kindle Fire offers FreeTime for kids, containing only content that’s acceptable and safe for children.

Now that tech giants are angling to make G-rated products and services, this market could move beyond niche into mainstream. And there are some effects we might not be taking into account.

Google’s and Twitter’s efforts are by no means pointing to a safe Internet exclusively for children, but they’re definitely trying to prune the content so kids don’t mistakenly stumble across something or someone that they aren’t prepared to deal with. But is it even possible to build such a layer of the Internet we’ve come to both love and hate? And if so, should we?

“Just like we have children’s sections for kids at libraries, I think having a child-safe part of the Internet is a no-brainer,” Dr. David Greenfield, founder of the Center for Internet and Technology Addiction and assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut, said in an interview with the Daily Dot. “As it is, you [have to] put in very specific block filters and monitoring, and then you only can do that in your own home or when your kids are on their own devices.”

Greenfield studies and helps treat the overuse and addiction of the Internet and digital technologies, and says that people, including children, lose track of time and space when they are online. By creating a space that is safe and only for children, parents can feel more comfortable with letting them roam freely.

But maybe there’s a harm in whitewashing the Internet, in putting limits and safety nets all over it.

https://twitter.com/DJSundog/status/569909080724099073

Dr. Winifred Lender, psychologist and author of the book A Practical Guide To Parenting In The Digital Age, said a digital plan for families (outlining which websites are safe to visit, who kids can interact with online, and other Internet restrictions) should be enough to prevent kids from coming across things they aren’t supposed to. But even if they do, content that isn’t necessarily appropriate for kids won’t ruin them.

“We want our children to develop a healthy appreciation and fear of the Internet,” Lender said. “They can understand it’s powerful but understand that there are some dangers there. Just as kids have to learn how to navigate walking to school or strangers, they do need to learn to navigate the Internet.”

“A lot of times, if we limit access to something, it becomes forbidden fruit.”

By boxing kids in to an app or service that provides only content the application decides to distribute means kids aren’t exploring and growing on their own. Despite the dangers, there is something special about discovering a new video or website on your own, and sharing it with peers.

In addition to the hyper-controlled resources that stifle imagination, Lender says that creating a space exclusively for kids can make adults rely on an iPad or laptop as a crutch for playtime. Like plopping a kid down in front of the television and walking away.

“Parents will relinquish the supervisory role and will not interface with kids around what they’re doing if there is this supposed 100 percent safe Internet,” Lender said. “Kids need to be talking, and kids need to be asking what’s going on.”

Kids between the ages of 8 and 18 spend seven and a half hours with connected devices each day, according to a 2010 study, and that number has almost surely risen in the past five years. And Lender says that unsupervised use of restricted Internet could increase that time even further.

“A lot of times, if we limit access to something, it becomes forbidden fruit,” she said. “The concern would be that by saying this is your Internet, you can’t come on the real one, it makes the ‘adult Internet’ all that more appealing.”

Building siloed services that effectively set up the kids table might be appealing to some parents, but flaws remain. For instance, it’s very hard to establish age restrictions on apps and services—adults could just as easily access online communities meant for children as parents who set up their kids’ accounts. And while some apps are created exclusively for families to communicate, it’s impossible to know who all end-users are.

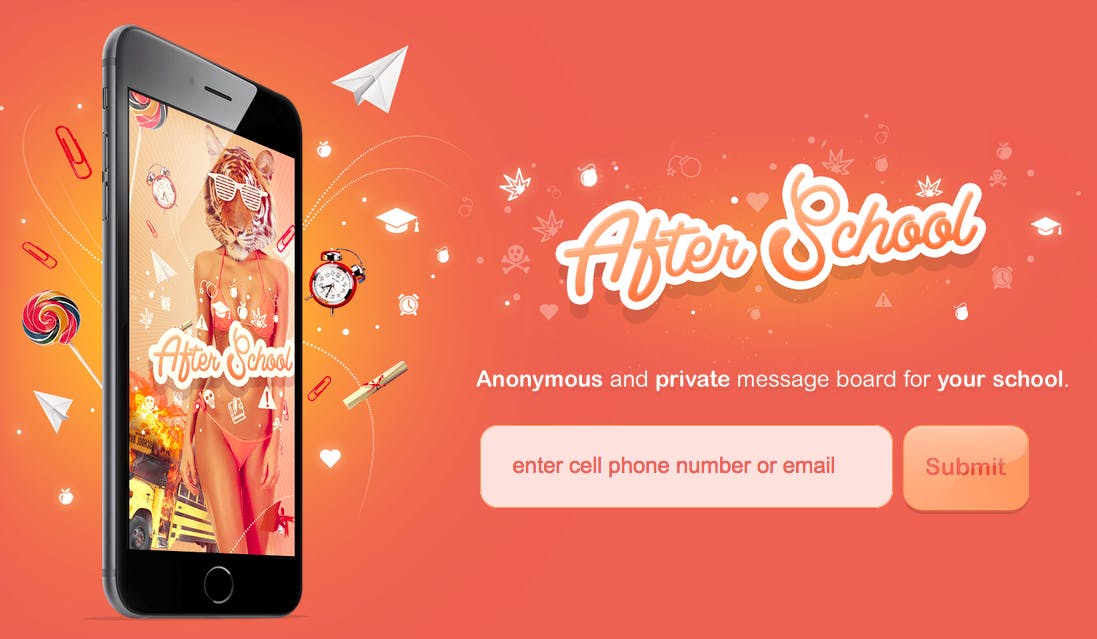

Snapchat and anonymous apps have a particularly troubled relationship with their young users. The apps cater to teens, yet some even come with age restrictions (despite the fact they are targeting high schoolers). Many of them are hotbeds for cyberbullying, yet another worry for parents. The applications do little to stem negative behavior or talk about consequences associated with them.

For a long time, many teens used Snapchat thinking their photos immediately disappear. As we, and they, have come to learn, nothing on the Internet disappears.

Snapchat has finally acknowledged that teens might be a little to sext-savvy, and recently updated its community guidelines to remind everyone under the age of 18 that sending nude or sexually explicit photos is not allowed.

Keep it legal. Don’t use Snapchat for any illegal shenanigans and if you’re under 18 or are Snapping with someone who might be: keep your clothes on!

Anonymous apps have attempted (to varying degrees) to restrict content. Most of them miss the mark, but some, like Yik Yak, are not only warning people about posting malicious content, but have also blocked students from posting while at school. Using the device’s GPS, the app blocks any attempts to post on Yik Yak anywhere in or near a high school.

Despite these improvements, Lender believes that apps largely used by young people aren’t doing enough to educate kids about what could become of their data.

“It would be nice to have a little more thought and education to the end user about how the apps could be used, reminding them that nothing ever disappears,” she said. “There is misinformation and kids expect that they can take any picture and it would be gone.”

Google, Twitter, and hundreds of other applications are trying to make the Internet safer for kids, even as the same companies struggle with making it safer for adults.

As more companies begin to adopt ways for young users to interact with their software and services, the onus remains on parents. For that, Lender suggests creating a digital plan instead of relying on teen- or child-only apps.

“It falls on parents too to really have a strong family digital plan that talks about when a new app comes out how the child will research and present it to parents, and how parents [make decisions on what tools their kids can use],” she said.

These new kid-safe applications are available for browsing and surfing. But there’s a great big world out there, and children will explore it eventually. The trick, for parents, is to make sure they’re being safe, no matter where they wind up. Easier said than done.

Photo via gaglias/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)