Two German teens have made a major breakthrough in disability tech with a low-cost eye-controlled manual wheelchair.

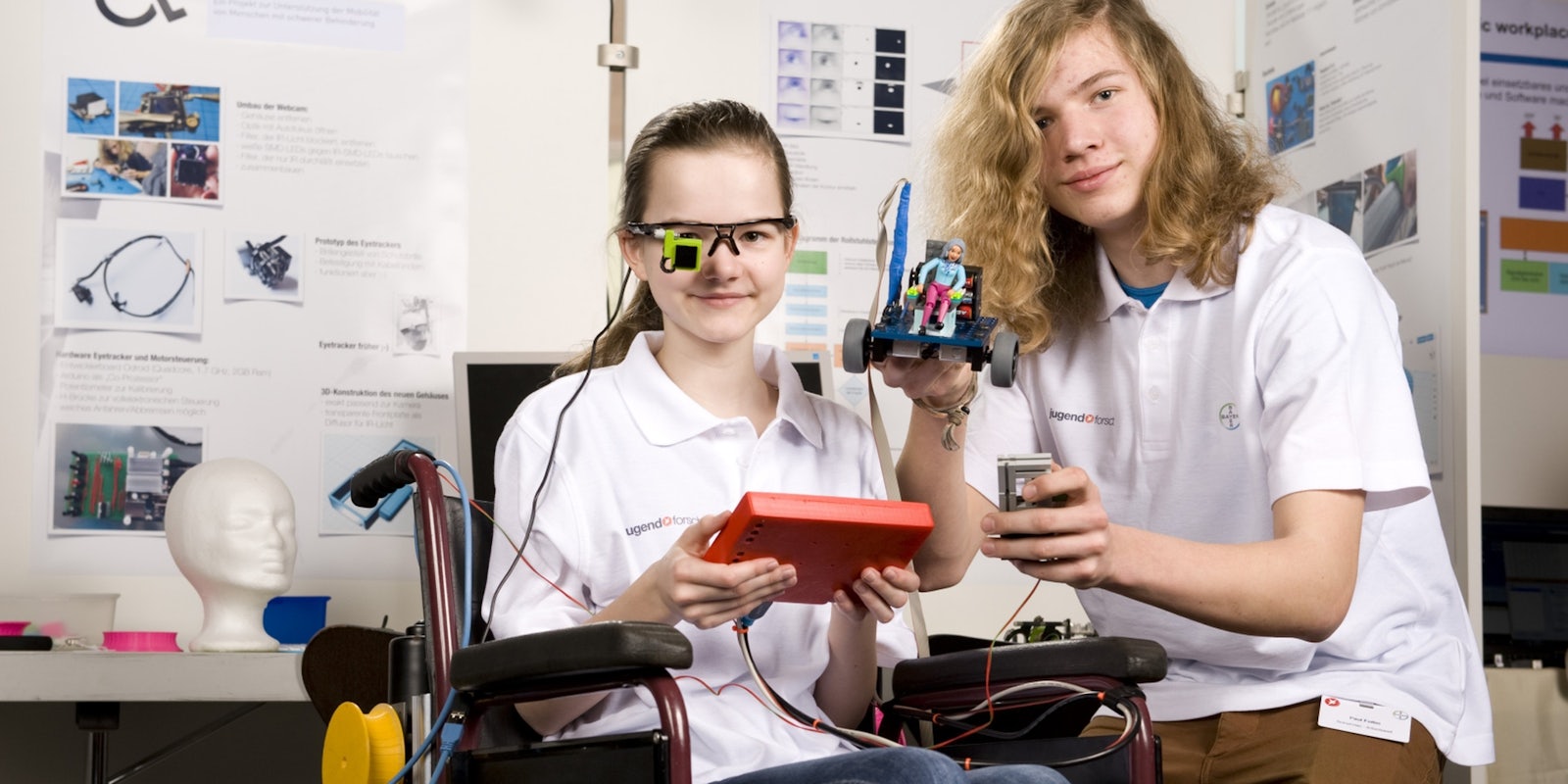

Myrijam Stoetzer and Paul Foltin won first prize in the “world of work” category in Germany’s Jugen Forscht, a competition aimed at promoting the work of young designers and engineers. Their open-source wheelchair represents an amazing revolution in disability technology as young designers at the forefront of tech develop basic tools to improve accessibility and increase independence for disabled people.

Wheelchair users have a variety of mobility needs, with many people relying on wheelchairs due to paralysis or conditions that interfere with motor control. From Stephen Hawking to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, people have used a variety of technologies to meet their mobility needs and increase their independence—a key value for the 20th- and 21st-century disability rights movement.

For many, manual wheelchairs are sufficient, with the user operating the chair by hand. Those with more complex medical conditions rely on powerchairs, manipulated with a control on the arm of the chair. Some users, like Hawking, lack the muscle tone needed to use a hand control and rely instead on chairs operated by twitches of facial muscles. Such control systems require custom fittings—not all users have the same degree of function and the chair needs to be painstakingly customized to their needs—and they can be quite expensive, which is highly cost-prohibitive for low-income disabled people and those without adequate insurance coverage.

“We wanted our project to be as cheap as possible to be affordable for everyone.”

Complete paralysis, locked-in syndrome, and related medical conditions can severely interfere with basic independence, as disabled people rely on aides to assist them with many tasks of daily living. Being unable to move, though, is a severe restriction on the ability to engage with society, which is what makes wheelchairs so empowering—and what makes this project so important: It puts low cost tools into the hands of any wheelchair user or organization providing assistance to wheelchair users.

“We wanted our project to be as cheap as possible to be affordable for everyone. Our aim is that this approach can be used widely and rebuild for people in need,” Stoetzer explains, reflecting the fact that a wheelchair can be a symbol of freedom for someone with limited mobility.

The wheelchair design uses an ordinary pair of safety glasses sans lenses, mounted with a webcam and a set of LEDs. The webcam’s IR filter is disabled, allowing it to work in low-light conditions as the LEDs illuminate the eye. The user operates the chair with eye movements that are processed via a Raspberry Pi 2B into a system that controls a manual chair—rather than a costly and heavy powerchair. To avoid accidental movements, the system has a safeguard, which was manual in early iterations but can be linked to muscle movements like twitches of the cheek or tongue.

The teens used an assortment of recycled parts—including windshield wiper motors—and custom-fabricated 3D materials to produce the surprisingly inexpensive project. Along the way, they taught themselves how to code, refining the project as they won a series of local and regional competitions before hitting the national stage. The use of 3D printing and very basic design makes the wheelchair highly flexible, allowing users to easily program in settings for their own eye movements as well as design their own muscle controls. Efficient parts fabrication further contributes to the low cost. This sets the project apart from highly expensive and sometimes cumbersome equipment used by disabled people with high-level mobility impairments.

The eye-controlled chair isn’t just remarkable because of its affordability. The teens have also released the entire project in open-source form, encouraging people to build on it and use it; Stoetzer has provided detailed documentation on her blog. This increases affordability and also ensures that the code and related materials can end up where they’re most needed: in developing countries, where mobility needs are often high but few resources are available to disabled people. Given that power chairs equipped with advanced controls typically cost tens of thousands of dollars, a cost-effective option paves the way to independence for those with injuries related to war as well as degenerative conditions like multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Similarly low-cost projects relying on 3D printing, recycled parts, and open-source code are powering advanced prostheses for people in the global south, along with tools for blind and low-vision people who need accessibility aids. Enabling the Future, for example, produces custom prosthetics at a fraction of the cost of their traditional counterparts. Meanwhile, designer Randy Geile develops basic wheelchairs using old bike parts and scrap lumber. Two other finalists in the competition, Patrick Buchenberg and Jonas Borth, designed an assistive device for blind people who use canes to increase their range of motion and knowledge about their surrounding environment.

Innovative projects of this nature are becoming more common, especially among young designers and engineers like Stoetzer and Foltin. Their mix of interest in solving technological challenges, willingness to self-educate, and sense of social responsibility is a powerful combination for communities that reap the benefits of low-cost accessible technology. Their commitment to open source is another key component of their work.

Liz Henry at Hack Ability writes of copyright and open source:

“We need more organized and more permanent repositories for open-sourcing and open licensing inventions, adaptations, and mods for access and mobility stuff…This sounds grim, but say you documented your great one-button invention with all the electronics diagrams, photos, and so on. What happens when you die?”

Making such materials readily available contributes to a larger body of work on disability technology—and, in addition, it takes power away from medical device firms, which often hold disability tech hostage with high prices and proprietary systems.

As a generation of youth who grew up in a tech-saturated environment comes of age, Stoetzer and Foltin are bringing their experiences and background with them and into the production of a huge range of accessibility aids. Even as they improve independence for disabled people, they’re also disrupting traditional paradigms about the design and sale of medical devices, rooting their work in the belief that everyone deserves independence. Stoetzer and Foltin’s project will continue to evolve in coming years as other engineers tinker with it and produce their own versions, illustrating the tremendous potential of open-source disability tech.

Photo via Myrijam Stoetze & Paul Foltin