When Facebook announced its legacy feature last week, people scrambled to decide who would control the personal information that would live on the Internet after they died. It’s something most of us don’t often think about, especially if we’ve never lost someone we connected with virtually. The vast amounts of personal data we’ve accumulated year after year will remain online for eternity; it’s a morbid and, honestly, frightening concept.

Facebook’s inclusion of a digital will is a much-needed feature for a service that formerly struggled with how to support family and friends once a user died.

Notifications from friends and family who’ve passed on are particularly jarring. My dead grandmother Liked a Facebook photo once, and I was prompted to endorse a dead friend on LinkedIn for skills he no longer had. So Facebook’s attempt at corralling posthumous behavior is admirable.

It’s not just the world’s largest social network that’s figuring out how to preserve virtual versions of users. Startups are also creating resources for people, and memories of them, to live on online.

“These so-called ‘virtual tombs’ are a bit like leaving everyone a scrapbook after you go,” Dr. Ramani Durvasula, clinical psychologist and social media researcher, said in an email. “For many people, social media is their way of maintaining a community in life. These virtual tombs will slowly proliferate into virtual graveyards, I suppose, [where you visit] a lost loved one. Instead of a drive to the cemetery, it may be a drive through the Internet.”

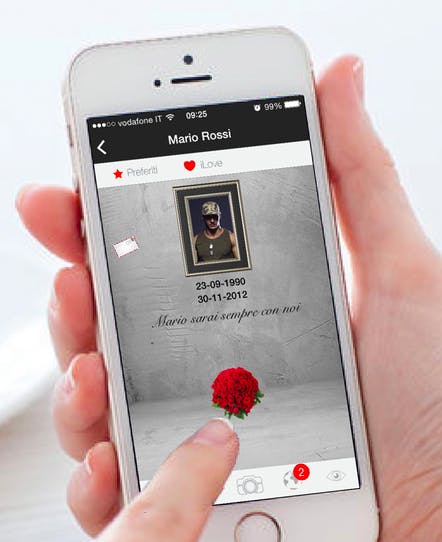

That’s the idea behind RipCemetery, a new iOS app that’s using Indiegogo to fund its development.

The Italian entrepreneurs behind RipCemetery built the application after a cousin died in a car crash and the family wanted to memorialize him in a virtual space. They wanted a sort of online graveyard, complete with the option to leave flowers on a tombstone.

Barbara Travagli, cofounder of RipCemetery, said that when her cousin passed, there was no way to honor him. His body had been cremated, and the impromptu memorial that was set up on the side of the road was destroyed by the natural elements. And being so far away from the accident physically, Travagli had no way of memorializing him herself.

“When this happened, I was in Australia,” Travagli said. “So I was thinking about people who were away from home, far away from friends and family.”

RipCemetery memorial pages allow loved ones to create tombstones, leave flowers, photos, and “Post-Rips,” or messages, on a “grave.” There are both free and paid options for leaving flowers behind, and the company gives you the ability to donate a portion of the fee to a nonprofit, likely one that’s involved in helping families who have suffered similar deaths, Travagli said.

While RipCemetery is based on a social media environment, it’s different from Facebook’s memorial page in that it removes application updates, invites to events, or post visibility that can reach hundreds. The privacy setting is determined by the owner of the account, and he or she can review posts before adding them to the virtual profile.

Evertomb is another company hoping people will pay for a digital afterlife. Much less earnest in its marketing, Evertomb acknowledges that such a Web page can be creepy; instead, it positions its services as if death is simply another step in your online evolution. According to its own description:

The possibilities are endless. Creep the fuck out of people, make people hilariously laugh, show greatness like a god of the internet and even use it as a resume to really get that new job.

“Few people can get their heads around the nihilism of death,” Durvasula said. “These virtual tombs may be a way for people to keep their own spirits alive. The pharaohs had the pyramids and their tombs—which they prepared while alive—these are really ways for those who are not kings and pharaohs to create their own tombs for people to excavate long after they are gone.”

Though the pharaohs of ancient Egypt were unlikely driven by the desire to “creep” anyone out, Amsterdam-based Evertomb’s rather cavalier reasoning behind building a digital afterlife takes those historical accounts into consideration.

Creating an online In Memoriam is as much about individual peace of mind as it is about assuaging the discomfort of friends and family. In RipCemetery’s promotional video, you watch a young woman periodically checking in on someone she lost. The woman leaves flowers, writes “I love you,” and shows her friends the virtual cemetery the person she lost is inhabiting.

“Instead of a drive to the cemetery, it may be a drive through the Internet.”

It reminded me of another (more fictionial and dysfunctional) life after death scenario. In Black Mirror episode 4, “Be Right Back,” a woman starts talking to her dead husband, first through an artificial intelligence version of his social media persona, and eventually to a real-life humanoid of the man she lost. While there are some modern versions of this AI-based grieving (like the Twitter-powered LivesOn or Bina-48), most virtual memorials don’t talk back.

But just because we can do it doesn’t mean it’s healthy.

“Mourning is different for everyone, but when you’ve got a Twitter account that’s active, in the dead person’s image and name, the relationship you have with that person who has passed is different than someone who let’s the social media life of the deceased die as well,” relationship expert April Masini said in an email. “There’s a daily presence of someone who is dead. For many, that is a great comfort. For others, it’s a reminder of the pain of loss.”

It’s impossible to know whether or not an online grave will bring more comfort than sorrow for the people you leave behind. Regardless, they’re now an option.

No one knows for sure what happens to us when we die, and this unknown brings a fear with it. Perhaps by taking control over what happens to our digital selves in the afterlife, we’re enjoying just a tiny bit of comfort. And maybe even trying to convince ourselves that some sort of immortality is possible.

Photo via Mark/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed