Try to define color. How would you describe the color of the sky on a clear, beautiful day to someone who’s completely colorblind?

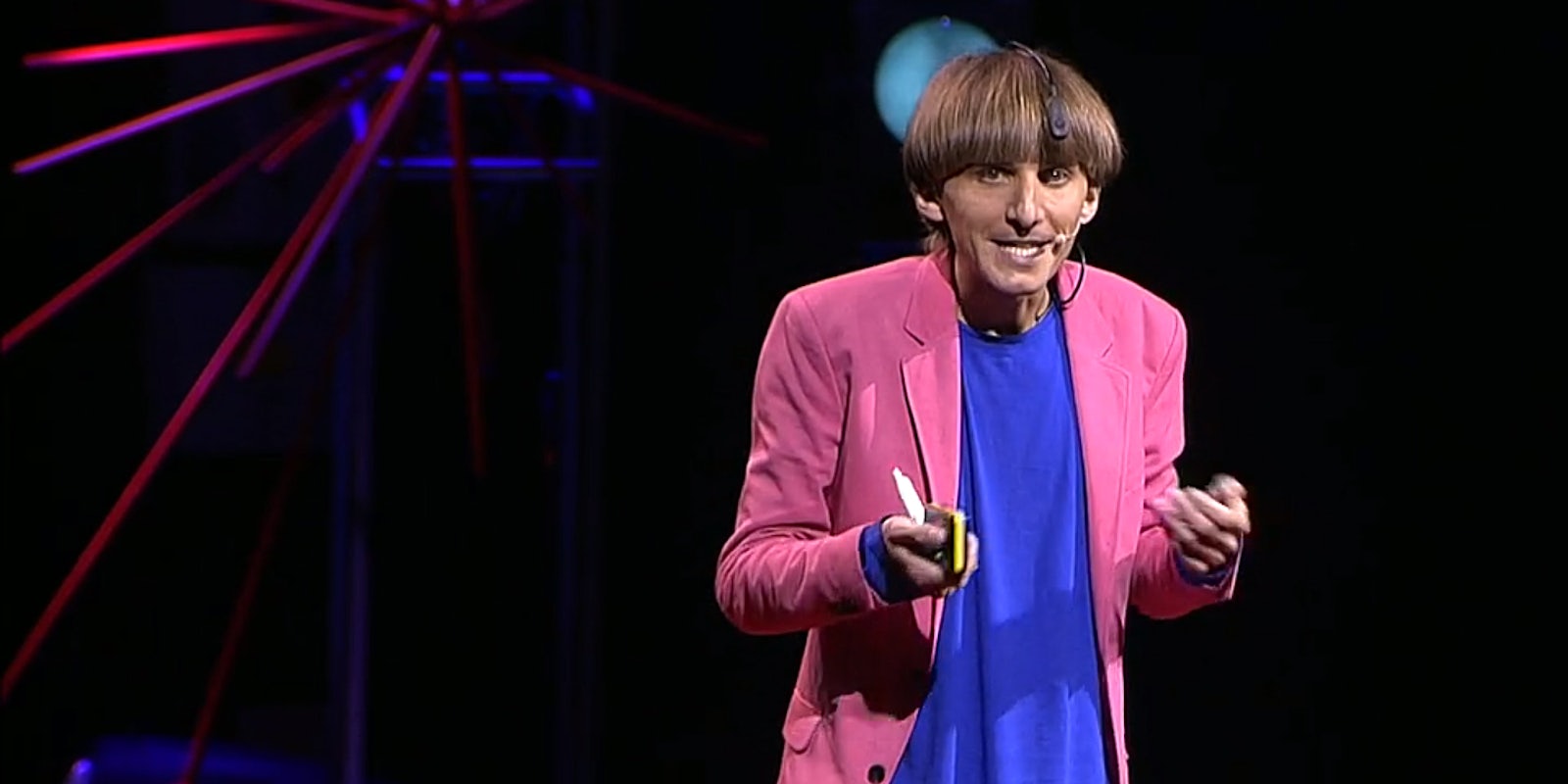

For Neil Harbisson’s family and friends, this was an everyday problem. Harbisson was born with synesthesia, meaning he can only see in black and white. “I come from a grayscale world,” he said in a TED talk in 2012.

While he was able to discern different shades of gray to understand the nuance of color—he knew that grass was “green,” bees were “yellow” and “black,” and so on—it wasn’t until years later when he attended a talk about cybernetics in college that he that he realized how cybernetic technology could enhance the way he sees—or rather, hears—the world.

Neil Harbisson is the world’s first cyborg. Surgically attached to the back of his skull is an antenna that he and a friend developed called the eyeborg. The bendable metal rod is equipped with a sensor that picks up on light frequencies and transmits them into his brain so that Harbisson hears the colors. Now an advocate of cybernetics and cyborg rights, Harbisson has dedicated his life to helping run the Cyborg Foundation, which he cofounded with his childhood friend, Moon Ribas, in 2010. The foundation aims to raise awareness about cybernetic technology and advocate for cyborg rights.

With help from his friend, computer scientist Adam Montandon, the two developed the eyeborg in 2003, an antenna attached to the back of Harbisson’s skull. Each color is prescribed a certain pitch. In between each color are more than frequencies that register more specific colors. Harbisson can hear more than 300 colors and has expanded his range to register infrared and ultraviolet lights.

Since becoming a cyborg, Harbisson’s world has hugely changed. He says it took him about five weeks to become used to the constant noise in his head, which now doesn’t phase him. During his TED talk, Harbisson explained how he chooses his clothing and meals based on what sounds good. “Before I dressed in a way that it looks good. Now I dress in a way that it sounds good,” he said of his personal fashion. He also does things like describing the pitch of Justin Bieber’s “Baby” as a color.

The antenna has revolutionized his world, and it’s a power he wants to share with others.

One way he’s already done that is through the Eyeborg app. By pointing a phone at an object, landscape, or pretty much anything, the app registers the colors and transmits sounds, just as the antenna that Harbisson wears does. The app is available for Android devices with an iOS version on the way.

It’s not so much that he wants to add to a market off accessory-like wearables that rely on user input, but rather enhance the existing senses that humans already have. For instance, being able to “hear” the strength of harmful ultravoilet rays on a given day could help people determine how much time to spend outside.

After deciding he wanted to implant the device permanently, he had to find a doctor willing to do the procedure. That doctor, Harbisson says, prefers to remain anonymous.

The Cyborg Foundation doesn’t just focus on “hearing” color. Another project, the 360-degree sensory extension, consists of a device attached to the back of the head. It vibrates when someone is approaching from behind, effectively extending our sight beyond the capabilities of peripheral vision. The speedborg is a device that vibrates at different intensities based on the speed of movements in front of the wearer. Versions of the device have been developed to attach to hands and to earlobes.

Harbisson told the Daily Dot that the foundation works with several universities around the world interested in helping advance cyborg technology. Through open-source coding, the technologies are easily accessible to anyone interested in seeing how it works.

The foundation also advocates for cyborg rights. Harbisson’s own journey to becoming a cyborg was a challenge. After deciding he wanted to implant the device permanently, he had to find a doctor willing to do the procedure. That doctor, Harbisson says, prefers to remain anonymous.

The most challenging road block is the ethics of the procedure, Harbisson says. Since becoming a cyborg is not a medical treatment, officials and lawmakers argue that the procedure is arguable unnecessary and creates a liability for doctors.

His own struggle with getting a passport allowed Harbisson to see that something needed to be done to educate the public about cyborgs. His case is unique, and there are not many other cyborgs in the world, but he believes that there’s no reason for them to be treated differently than any other person.

The Cyborg Foundation plans to open a new office in New York City in 2015. The move to the United States seemed like a natural progression for the foundation, Harbisson said. The foundation got its start in Barcelona before opening a second center in London. But in America, there seems to be a wider acceptance toward Harbisson’s interests. Harbisson said he feels more comfortable walking the streets of New York than he does in Europe, as his antenna seems not to phase people he passes on the street. Everyone minds their own business, he said, but he also feels that Americans are open to the evolving manner in which technology plays a role in everyday life.

With the move to America, Harbisson also hopes that the Cyborg Foundation will tap into the network of researchers at universities across the nation as well as their resources.

Like the foundation, Harbisson’s own eyeborg is a constant work in progress. The capabilities of the lens on the device has gotten stronger, and said in an interview with Not Impossible Now that he’d like to one day have lens that can be submerged into water, which he currently can’t do.

With the wearable market growing and researchers looking for ways to blur the lines between the human body and technology, the Harbisson’s work with the Cyborg Foundation is only beginning.

Neil Harbisson/TED