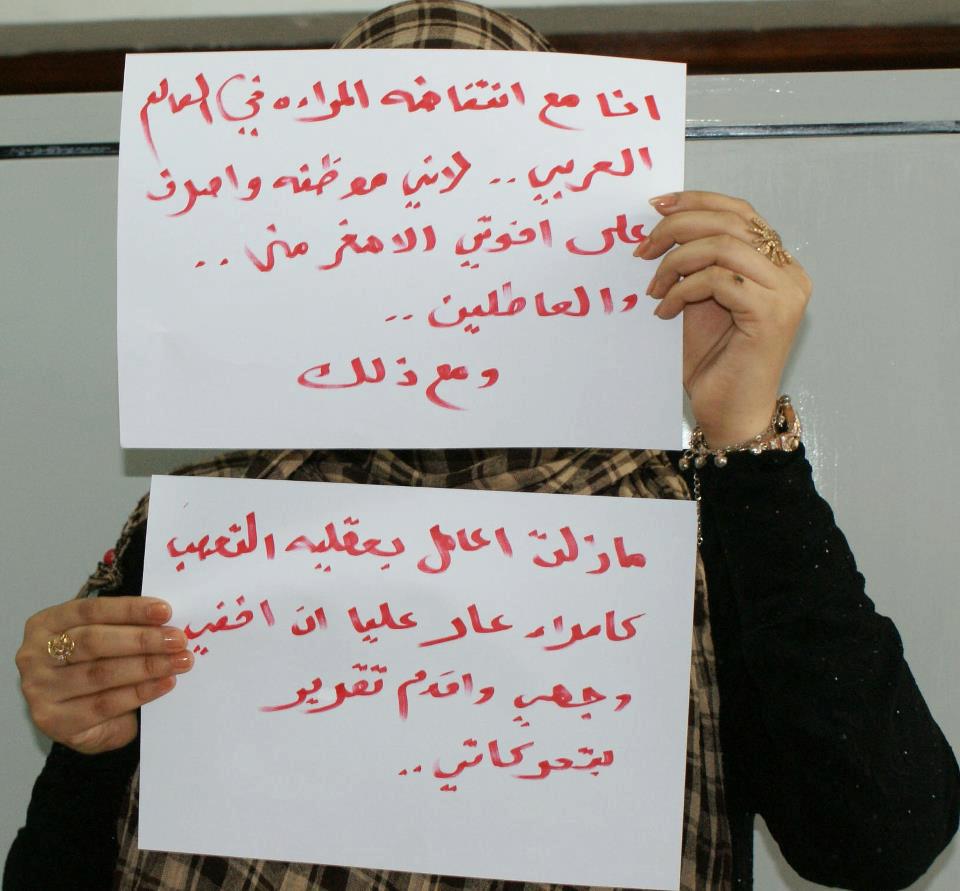

With one photo, a young woman highlighted her struggles living in Yemen’s patriarchal culture.

Wearing gold rings on both hands, Nour shields her face with two sheets of paper, with Arabic text scrawled across them in red ink. An English translation reads:

“I’m with the uprising of women in the Arab world because I am an employee and support my younger brothers and the unemployed. However, I am still treated with the mentality of intolerance. As a woman I have to hide my face and report my movements.”

The powerful image was shared on The uprising of women in the Arab world, a Facebook page that serves as a rallying post for a growing community of people pushing for stronger rights for women in the Middle East. Nour’s story is just one of hundreds shared by women and men on the site, helping spark a global conversation about life in Arab countries.

It almost goes without saying that women do not have anywhere close to the same rights as men in most Arab nations. Women who are raped are forced to marry their aggressors in several countries. Many can’t open a bank account for their children without their husbands being in attendance. Street harassment is also a common occurrence. In recent weeks, amid protests against Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi in Cairo, several women were assaulted as they attempted to voice their opinions. (One group tried to help stamp out such aggressions as they sought volunteer “bodyguards” and organized the movement through a Twitter account.)

While Twitter and Facebook have played a role in the overthrowing of governments and orchestrating widespread protests, especially in the Middle East, Yalda Younes, one of the five administrators of the Facebook page, said she started it in October 2011 because she was “pissed that even after the Arab Spring, women’s rights were not a priority.”

“We’re not five people behind this page we’re really 70,000 because the members are so active,” enthused Younes, a Paris-based a flamenco dancer and choreographer originally from Lebanon. “This gives us a lot of energy, because everyone’s putting so much into it. People you don’t know from all over, who consider it as their baby and fight for it.”

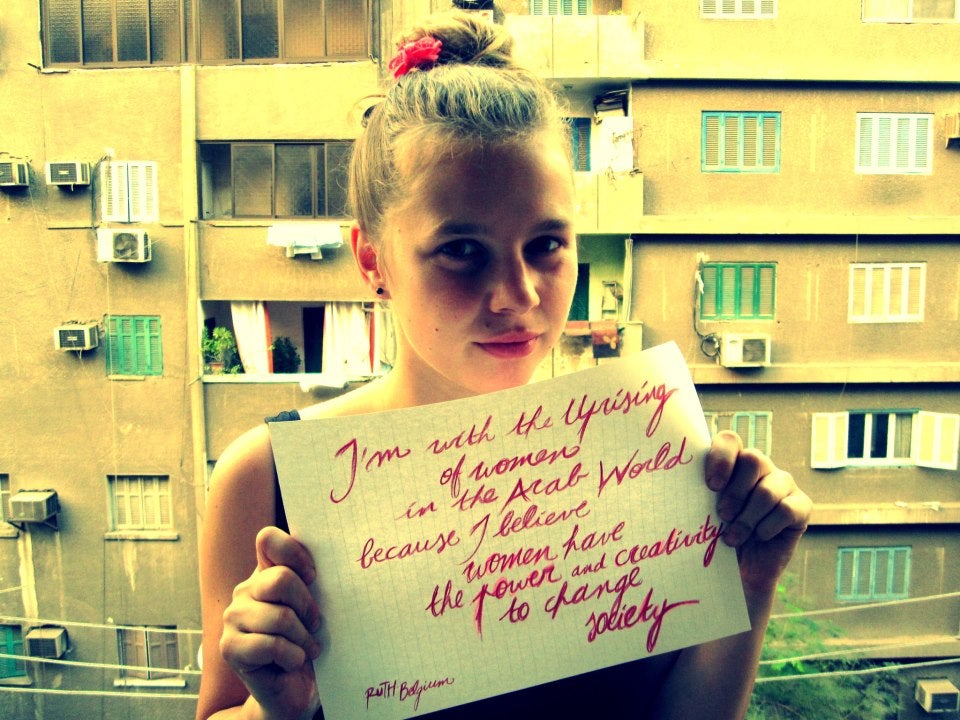

Ruth, originally from Belgium and now living in Cairo

The drive to include as many people as possible means offering versions of photos, updates, and stories in multiple languages, with followers often providing Arabic-to-English translations (or vice-versa) for every post. Submissions routinely have hundreds of likes and dozens of comments.

One campaign, in which backers of equality submitted photos of themselves holding signs pledging their support, was a pivotal success. Almost 1,000 photos were posted to the page, with Palestinians, Yemenis, and Syrians the most active in sharing their portraits.

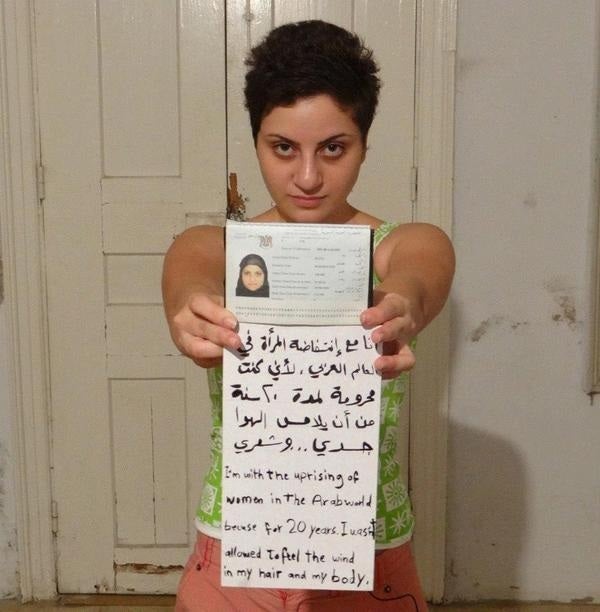

One image in particular stood out. Not for its message, which echoed hundreds before it, but because it led to temporary Facebook bans for the the page admins. The image depicted an unveiled Syrian woman named Dana Bakdounes (shown above), holding a sign and a passport photo. (It was the passport page and the apparent sharing of someone else’s personal information that brought the ban.)

The incident sparked some controversy. Bakdounes received a death threat over the photo, but she told the BBC “everything has changed for me since I took my veil off” in August 2011. Following the photo, she said she was happy to receive many messages of support from “girls wearing the veil.”

Facebook offers a degree of physical safety for those who want to discuss the issue of women’s rights with extremists on a rational battlefield. Yet, given the sensitive nature of the subject matter, admins have to carefully curate the content so that sexually provocative and potentially inflammatory images don’t derail the greater conversation taking place.

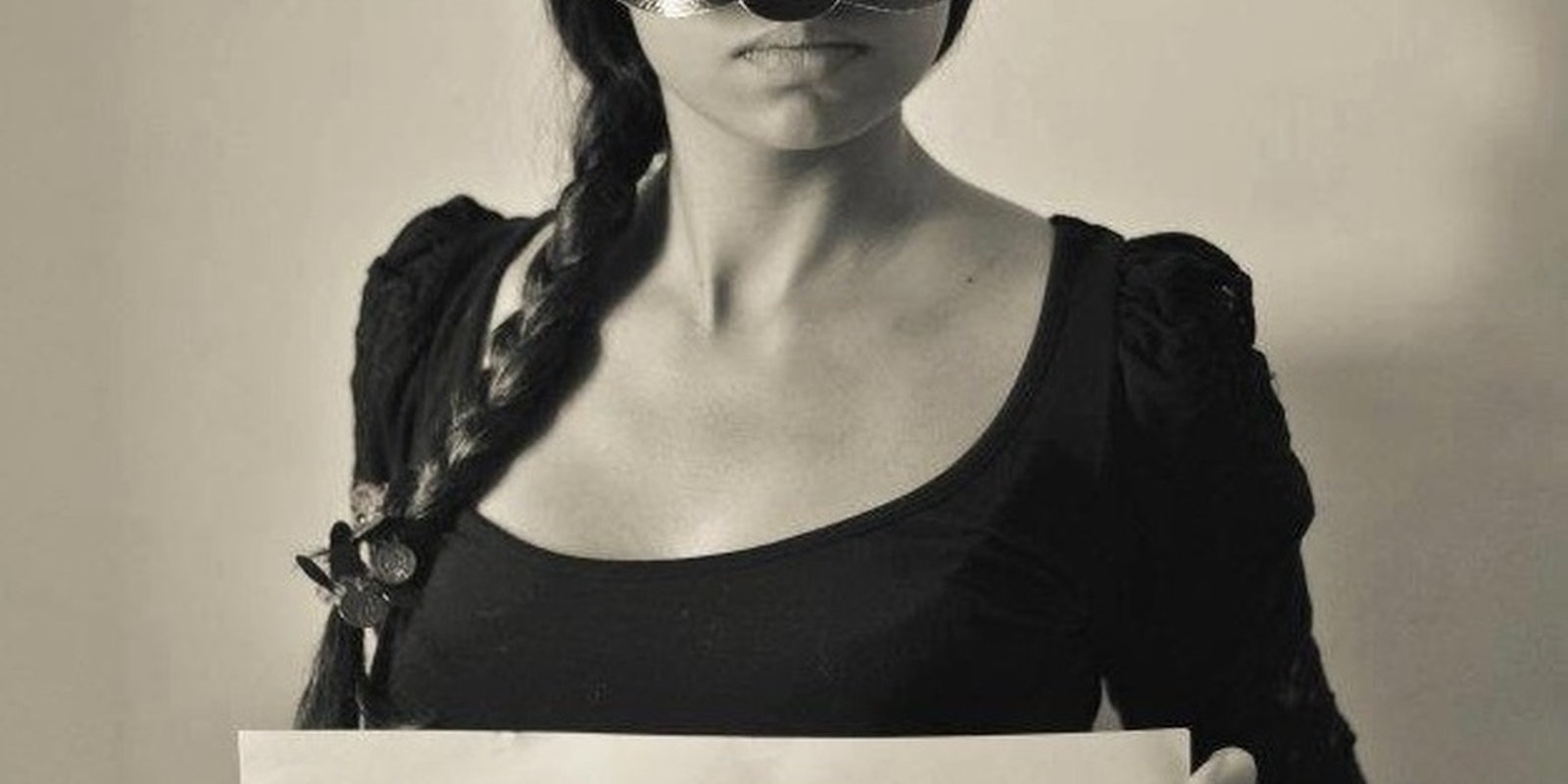

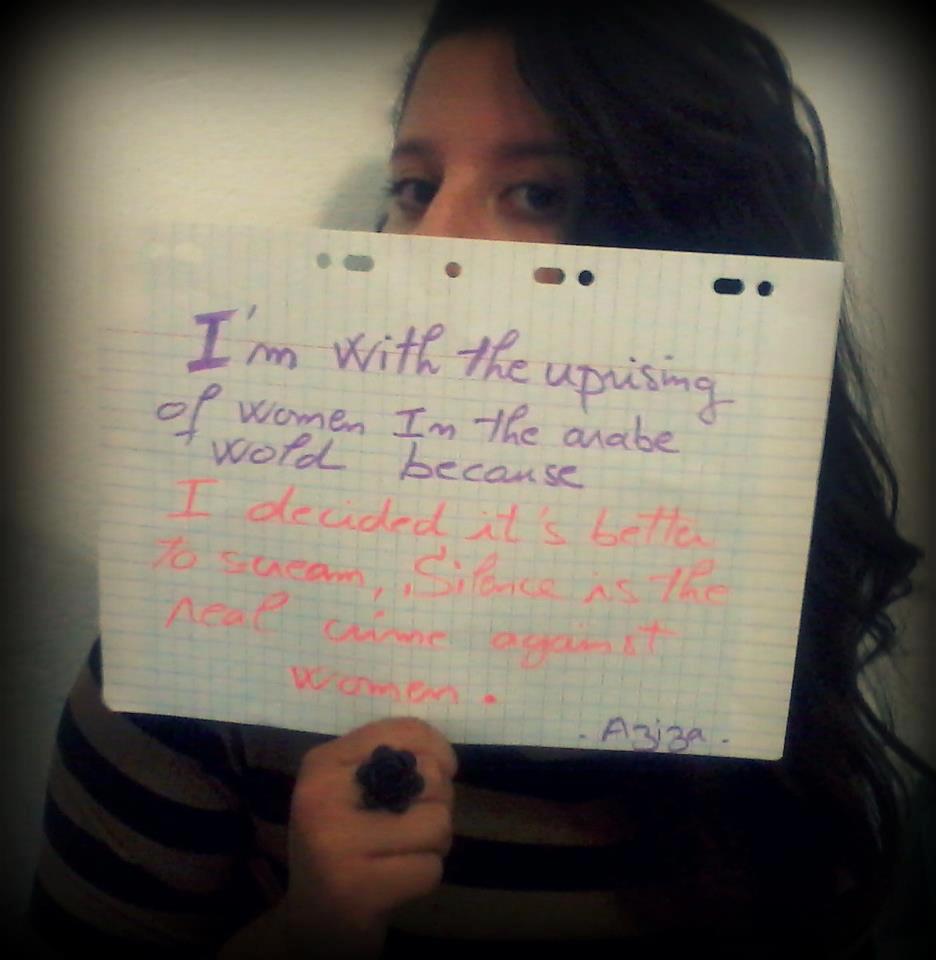

Aziza, from Tunisia

Younes noted that there’s also problem with Western residents who participate in the discussions, since many assume women who are veiled are obliged to be so. Those commenters want to free those women from such constraints, whether they want to be liberated or not. This, of course, is an issue in France, where Younes lives and the veil is banned in public places.

“I should be able to walk down the street disguised in whatever I want and whatever veil I want without being judged,” she said. “It’s very clear that the page is a secular space that defends the right of a woman to show her body if she wants and to unveil, but also to wear her veil without being judged as or only seen as a veiled woman.”

That’s why the uprising of women in the Arab world page finds such strength in first-person accounts. It gives supporters the opportunity to expresses themselves in their own words, without censorship or stereotypes.

Recently, Nada Thakeb wrote how she and her sister were assaulted amid a crowd of at least 30 men. Deema told of being molested by her uncle as her mother made her feel as though she was the guilty party. Ghina, from Lebanon, said she is unable to ask her husband for help around the home since “it will hurt his ego and he will make a bad reaction.”

These stories, a few of dozens of tales of abuse, provide a stark look at a tough existence endured by many women.

“Every one of us has a story you hide under your pillow because you’re ashamed of it or because society makes you feel that you’re the one who’s guilty and not the aggressor,” Younes said.

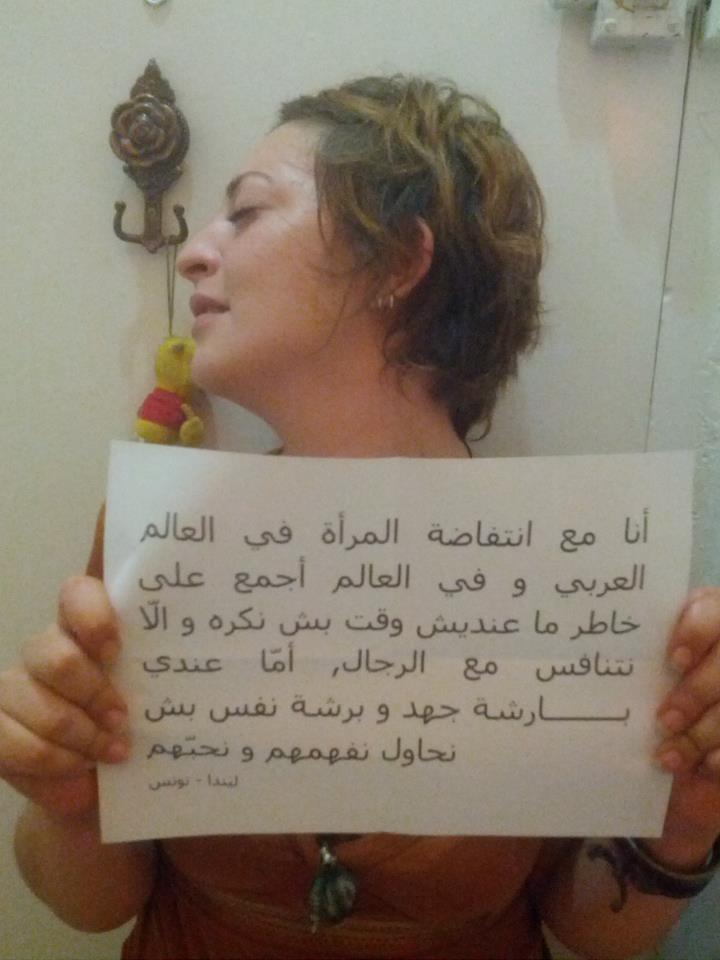

Linda, from Tunisia: “I’m with the uprising of women in the Arab world because I have no time to hate men and compete with them, but I have a lot of time, much more strength and a long breath to understand and love them.”

The page has brought tangible change for at least three women who shared their experiences of being raped. One said her mother told her not to say anything, because it would cause the family a scandal. Another was raped by her father for 17 years, and her mother said she was to blame. Younes said the women claimed their “life has changed after the campaign.”

The page gave the women a much needed outlet and support system to start the healing process, helping them reconcile with their bodies and to start believing that they deserve happiness again.

“This alone makes it all worth it,” Younes said.

Photos via The Uprising of Women in the Arab World/Facebook