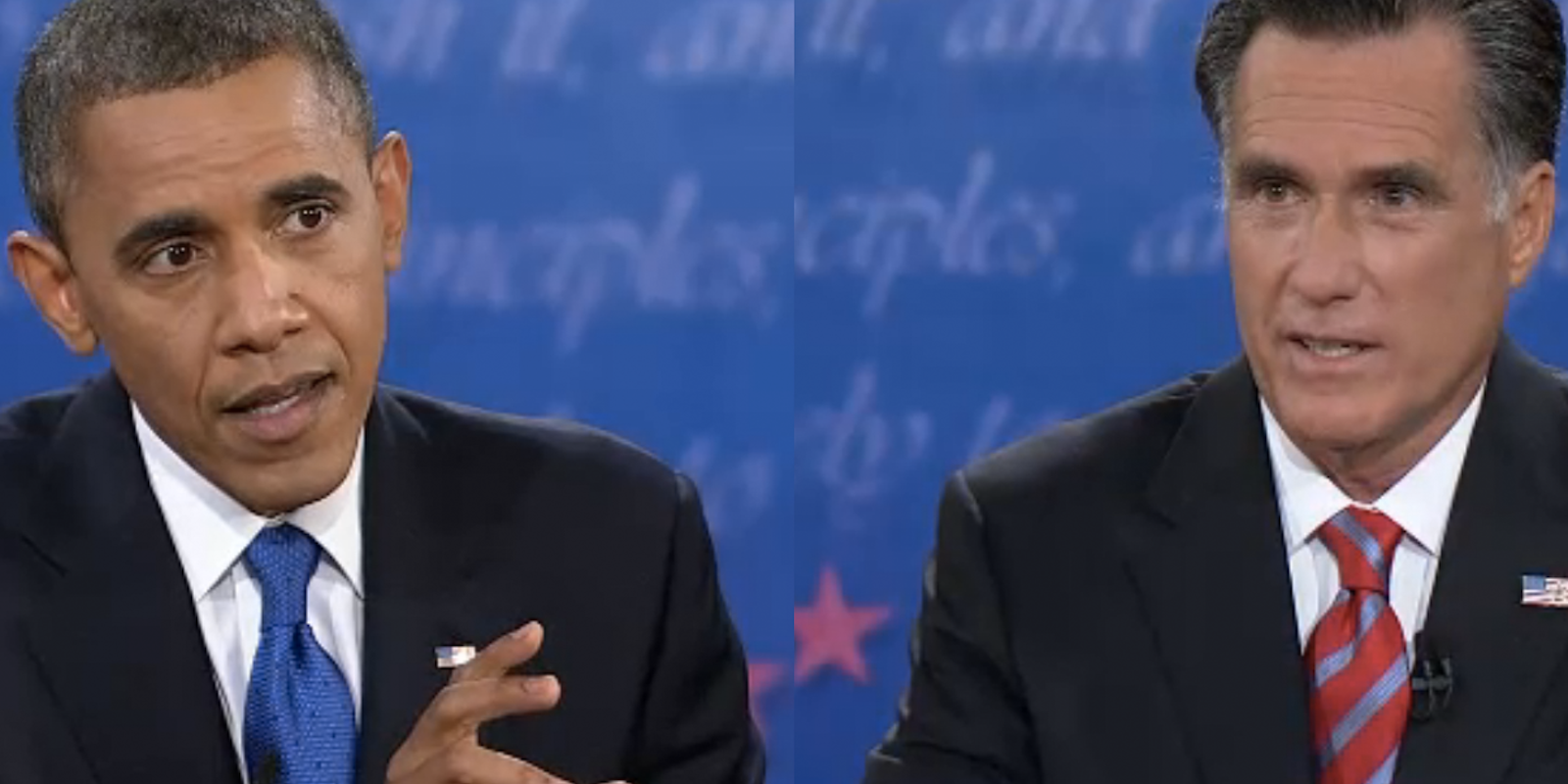

President Barack Obama and former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney have spent four-and-a-half hours in televised debates—and hundreds of millions of dollars in campaign ads—to convince you that each has the better position on all sorts of issues. One topic the candidates have refused to bring up (though not for lack of activists’ trying), however, is if and how they plan to protect Internet freedom.

Make no mistake—Internet freedom is a political issue, albeit not a partisan one. One needs to look no further than the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and Protect IP Act (PIPA), sister bills brought to Congress in January that many experts thought could mean the end of the Internet as we know it.

Those bills were defeated only after the Internet “went on strike” Jan. 18, and members of Congress were swamped with calls from concerned citizens. SOPA and PIPA weren’t one party’s purview, either. They were authored by a Republican and a Democrat, respectively, and their most outspoken critics in Congress were a Republican and a Democrat, respectively.

So how do Obama and Romney stand on the two biggest threats to Internet freedom in America today—overzealous copyright enforcement and cybersecurity? Here’s what we know.

Open Internet versus copyright lobbyists

Copyright enforcement and Internet freedom aren’t necessarily exclusive terms, but groups that fight for one often end up opposing the other. And both Obama and Romney walk a delicate line between the two.

SOPA and PIPA, for example, were both born of intense lobbying from industry groups, like those representing the music and film industries, that want to protect copyright at nearly cost. Those bills were meant to stamp out Web pirates, even if doing so meant that any site that contained any offensive link, no matter who posted it, could be taken down. And these lobbyists expect their money to give them a say in such laws: Chris Dodd, the head of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), infamously threatened to cut contributions to politicians who didn’t support SOPA.

Both Romney and Obama took strong stances against those bills as they neared their votes in Congress and may have combined to sway momentum against them. “Besides the protest,” Trevor Timm, a representative of Electronic Frontier Foundation, told the Daily Dot, “both candidates together were actually the reason that the bill was killed.”

Then competing in the Republican primaries, Romney was one of the first candidates (in addition to Ron Paul, an outsider to conventional Republicans but a cult hero on the Internet), to oppose SOPA. At least as far back as December, Romney made an argument not dissimilar from the one heard on the Internet 2012 bus—that SOPA, as a threat to the Internet, was thus a threat to small businesses, and therefore, a threat to the economy.

Obama, for his part, released a statement that, while not mentioning SOPA or PIPA by name, condemned copyright laws that resembled them—though he did offer concessions to the entertainment industry that lobbied for them:

“Let us be clear online piracy is a real problem that harms the American economy, and threatens jobs for significant numbers of middle class workers.”

“The statement [named] all of the specific protections he would need to see in a copyrighted bill, none of which were in SOPA,” Timm said. “[Obama’s and Romney’s] comments together really doomed SOPA as much as the protest did. In that respect they were both helpful to Internet freedom.”

Before you start thinking too highly of these two men’s willingness to stand up to the copyright lobby to protect the Internet, note those are just two bills. The opposite, so far, has been the case with the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a multinational trade agreement that could dictate online copyright law for all participating countries. The TPP, activists say, is a threat to the Internet, and U.S. copyright lobbyists have similarly played a role in the TPP’s continual development. Ambassador Ron Kirk, who represents the U.S. in TPP negotiations, was directly appointed by Obama. Romney reportedly supports the TPP so much, he wants to “fast track” it and move on to more, broader trade agreements.

Both candidates receive significant campaign contributions from the entertainment industry. In 2011 alone, according to figures disclosed by opensecrets.org, the combined music, movie, and television industries gave more money to those candidates than to anyone else in their respective parties. Obama received significantly more, though: $2,602936 to $226,535.

On the issue of cybersecurity

Seemingly every politician is concerned is the U.S.’s reportedly weak cybersecurity, stressing that the country is particularly vulnerable to online attacks and needs a new law to address it. What such a law would look like falls roughly along party lines.

Democrats want to encourage companies to individually adopt stricter, nationally mandated standards. Republicans want to increase “information-sharing,” meaning that private companies can bypass privacy laws when they’re being hacked and let government agencies, like the Department of Homeland Security, view their systems. The Democrats’ bill, the Cybersecurity Act of 2012 (CSA), was defeated in the Senate in August. A Republican-backed information-sharing bill, the Cyber Intelligence Security Protection Act (CISPA), passed the House in April.

Obama’s stance on this is clear—kind of. He long supported CSA and flat-out promised to veto CISPA if it ever passed the Senate. CISPA, it should be noted, is “a privacy nightmare,” Timm said, since it would allow “companies hand over large swaths” of people’s private information “to the government, without a warrant.”

When the CSA was defeated, Obama got to work on drafting an executive order based on that bill, noting that Congress, entering its lame duck session, clearly wasn’t going to pass any cybersecurity measure anytime soon. Though the exact content of his order hasn’t been revealed, the latest report on it indicates that it makes a clear compromise: CISPA-like provisions for “critical infrastructure,” presumably like electric grids and power plants, and no information-sharing for the rest of the Internet.

Romney, by contrast, has been largely mum on cybersecurity in public appearances. (His campaign, as did Obama’s, ignored multiple requests for comment for this article.) However, his official platform does address the topic, noting that while “President Obama has taken some positive steps to confront” cyberattacks, “private-sector theft” is a priority that he would address.

Why is this important? Because whether a politician wants cybersecurity simply to protect from terrorist attack, versus wanting a bill that protects infrastructure and private businesses, is probably whether they support a bill like the CSA or one like CISPA. The CSA was voted down in the Senate after it was condemned by the Chamber of Commerce, a lobbying group supporting business interests.

“It was pretty clear that a lot of Republicans voted against the CSA because they wanted more of those information-sharing provisions,” Timm said, noting that would be good for a lot of businesses, because they government could immediately help them out when they’re hacked, but bad for privacy.

A source with intimate knowledge of CISPA’s creation told the Daily Dot that a part of that bill’s urgency came from Chinese hackers’ practice of stealing valuable trade secrets. But offering government help to private businesses that are being hacked will probably be largely outside of the CSA’s reach. That’s the price of keeping the government from being able to sift through, for instance, Facebook’s’ files.

In the third presidential debate, Romney seemed to confirm that he thinks the U.S.’s need for cybersecurity is related to industry, and by extension would prefer a bill like CISPA. In his sole cybersecurity-related statement, he said that Chinese hackers are “stealing our intellectual property, […] our technology, hacking into our computers.”

Your privacy

For his part, Obama created what he called a “Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights,” designed to regulate how companies can track your online activity. But it’s still in the hands of the Senate’s Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee, tasked with tweaking it and introducing it as a bill. Romney’s plan, on the other hand, simply doesn’t mention online privacy. “Mitt Romney hasn’t really said anything yet,” Timm confirmed.

However, Obama does have a glaring hole in his privacy record: renewing the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), which gives government agencies vast powers to watch over citizens’ online activity, such as when they send emails, without a warrant. FISA is now used to track online activity but was originally written to dictate how the FBI could wiretap someone’s phone. Obama even campaigned on reforming FISA in 2008.

As recently as his Oct. 18 appearance on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, though, Obama insisted that when FISA was renewed, those who worked on the bill “built a legal structure and safeguards in place” to protect privacy. But that simply isn’t true, Timm wrote at on the EFF’s website:

“To the contrary, there’s no indication that the still-active warrantless wiretapping program—which includes a warrantless dragnet on millions of innocent Americans’ communications—has significantly changed from the day Obama took office.”

Romney did formally endorse FISA in 2007, when then-President George W. Bush renewed it.

So who’s better for the Internet?

The EFF doesn’t endorse a candidate for office and couldn’t even if it wanted to. Since it’s a 501(3)(c) nonprofit, that’s illegal.

But even if he could, it’s tough to answer. “There’s a whole host of issues we just don’t know the answers to,” Timm says.

We don’t know what Obama’s executive order will say or if Romney has any plans at all to protect user privacy. We don’t know if either candidate is even aware of activists’ concerns with the TPP. Neither candidate has signed the Declaration of Internet Freedom, a document consisting of five simple, clear principles of what constitutes a free Internet. (Only five members of Congress have signed it since its creation in July.)

Clearly, neither candidate is perfect, but as evidenced by SOPA, both will take heed if an Internet-threatening law becomes an issue dear to enough Americans.

So do you prefer the devil you know? Better yet: Do you know either of these two at all?

Correction: A previous version of this story mistakenly quoted Trevor Timm as referring to FISA as “older than the world wide web itself.” Timm was actually referring to the Electronic Communications Privacy Act. We regret the error.

Screengrab from third presidential debate via AOL