The Office of National Intelligence has declassified a secret court ruling that reveals the legal underpinnings of the National Security Agency’s controversial email metadata collection program.

As documents leaked by former intelligence contractor Edward Snowden previously showed, the NSA’s tracking of where and when Americans’ sent emails dates back to the Bush administration. The spying continued until 2011.

During that time, the email monitoring program was overseen by the secretive Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which was created in 1978 to regulate the government’s surveillance practices.

On Monday night, in an effort to foster a more transparent image in the wake of Snowden’s damaging leaks, the Office of National Intelligence released the FISC’s 87-page ruling in 2004 on the legality of the program.

The court wrote that the program marked a “much broader type of collection than other pen register/trap and trace applications,” a holdover term from a time when pen registers were used to tap telegraph lines. In modern times it is used to refer to the collection of metadata (such as call times or email destinations) in cases where the content of communications is not held.

Apparently, after the government initially submitted its request to conduct email surveillance, the court found “First Amendment issues presented by the application.” What those issues were exactly isn’t clear.

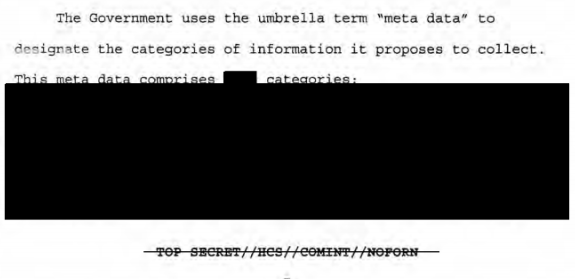

The court seems to have considered what information could be learned from the data when collected and analyzed in certain “categories.” The ruling limits what categories of data can be collected in what appears to be an attempt to limit what analysts can learn by processing the information.

The descriptions of categories were witheld.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the document is the redactions themselves. A good portion of the opinion is spent on defining what metadata is and how it is collected. While the document clearly confirms no “content” was collected, the actual definition of what constitutes metadata is completely blacked out:

The redaction continues for the next two pages, followed shortly after by the line “but this isolated fact does not provide ‘information concerning the substance, purport, or meaning of the email.’” What that fact is, like the government’s definition of metadata, remains secret.

Photo by Mihai Bojin/Flickr