I like to play this game on Tinder where I look at a profile for just a few seconds and react with my initial feelings—left “no,” right yes.” I call this “The Beyoncé Game” (because…to the left, to the left). Recently, I was playing this game and got more bored than usual. So I decided I should switch it up and maybe try messaging people for a change. Start actually seeing who all these Mr. Rights were that I had compiled over the months.

As I went through I began to see a trend: All of the men looked the same. They were all white with brown hair. They all had facial hair, and they all ranged from mid-to-late 20s. And in all actuality, they could have been brothers. At first I thought it was humorous. Wow, I must have a type, I thought to myself. But suddenly, I realized something: There were no people of color. As a black person I immediately asked myself: Wait, am I racist?

Racism is a hot button topic in numerous realms ranging from social to political, religious to entertainment. However, the one area where racism seems to get a pass is when it comes to love and attraction. Many people argue that who we like is completely out of our control, simply labeling it as a “preference.”

During conversations around love and race, preference is the one card thrown fastest on the table whenever people are asked why they only date people of one race compared to another. Whenever I am personally engaged in this conversation and preference is used as an excuse when people say “I don’t like [insert race/ethnicity],” I usually ask: “So you’ve met every person of that race/ethnicity and you know you don’t like any of them?”

In his new book, Dataclysm: Who We Are (When We Think No One’s Looking), OkCupid co-founder and data scientist Christian Rudder takes a more in-depth look into the world of online dating. When the topic of race and dating comes up, he states that, “When you’re looking at how two American strangers behave in a romantic context, race is the ultimate confounding factor.”

This statement is in large part based on race and attraction data they started collecting in 2009 until now, where they found black people and Asian men are consistently the least desired on the site. They also found that black women were the least likely to be messaged, and white users were more likely to be messaged or responded to.

Rudder also took the conversation around race and dating onto the OkCupid blog, OKTrends, to answer some questions that come out when people read their findings. When Rudder answered the question: “Are you saying that because I prefer to date [whatever race], I’m a racist?” he surprisingly says “no,” because even he leans on the side of preference and believes that our attraction on an individual level is not a choice.

When reading this, I was shocked.

I couldn’t understand how such a huge trend could be written off so quickly with: “This is no one’s fault; we have no responsibility around racial relations when it comes to dating, even though people are openly making decisions with race on their mind.” As a person who experiences racism, or at least varying treatment from people due to my race, on a daily basis, I’ve learned that nothing is truly out of our responsibility when it comes to one another. Especially with love and attraction.

In 2006, New York University neurologist David Amodio and his colleague Patricia Devine conducted a study with over 150 white college students. During the first part of the study, Amodio and Devine asked participants to categorize words as either pleasant or unpleasant, and mental or athletic.

Before the task began, the students were shown black or white faces. The results showed that these students were faster at categorizing unpleasant and physical words when shown a black face and were faster at categorizing pleasant and mental words when shown white faces. Their results showed that even the most liberal minded people associate “black” with “bad.” The test used to explore these results is commonly referred to as an Implicit Association Test (IAT).

The IAT was introduced in academic literature in 1998 and is a measure commonly used in social psychology to detect the power of one’s automatic associations with objects and images, like we see in Amodio and Devine’s work. The IAT has been used in over 200 published studies, all of which showed how implicit bias affects behaviors in important ways.

If you take an IAT, you may notice a familiar feeling. The test feels like being on Tinder.

The basis of an IAT is to show the participant an image or object and ask them to associate it with a word. Through those pairings, scientists can begin to see how the unconscious brain files things away.

When evaluating people who consider themselve to be unbiased—claiming for example, not to discriminate on the basis of gender—the IAT often proves otherwise by revealing our deep, subconscious attitudes. And the test consistently shows us that bias, especially when it comes to bias linked to identities and groups, is something that is ingrained in all of our brains.

While Tinder has not been used for academic purposes in the ways that IATs have been, it would not be too farfetched to look at Tinder like an IAT. It does the same thing, showing us an image and forcing us make a decision based on first impressions, but with different goals. The IAT is used for science, while Tinder is used for love—or at least the participation within a romantic social sphere.

But let’s take a second and consider the possibility that how we inherently use Tinder, especially if you use a method like mine, not only shows us who we prefer. Instead, it shows us that our preferences are based not in something we can’t control—but in something we can, if we try to. My continual swiping to the right on tall, bearded white men isn’t just some preference, but something that is very much rooted in living in a world that tells me that white is beautiful, and black is not.

During an interview earlier this year on his implicit bias work, Amodio told Mother Jones that “the human mind is extremely adept at control and regulation, and the fact that we have these biases should really be seen as an opportunity for us to be aware and do something about them.”

I agree with Amodio. Just because we have a preference or an implicit bias towards something, it doesn’t mean we must act on it. We have the ability to change, if we really want to.

It’s just up to you if you want to start swiping right.

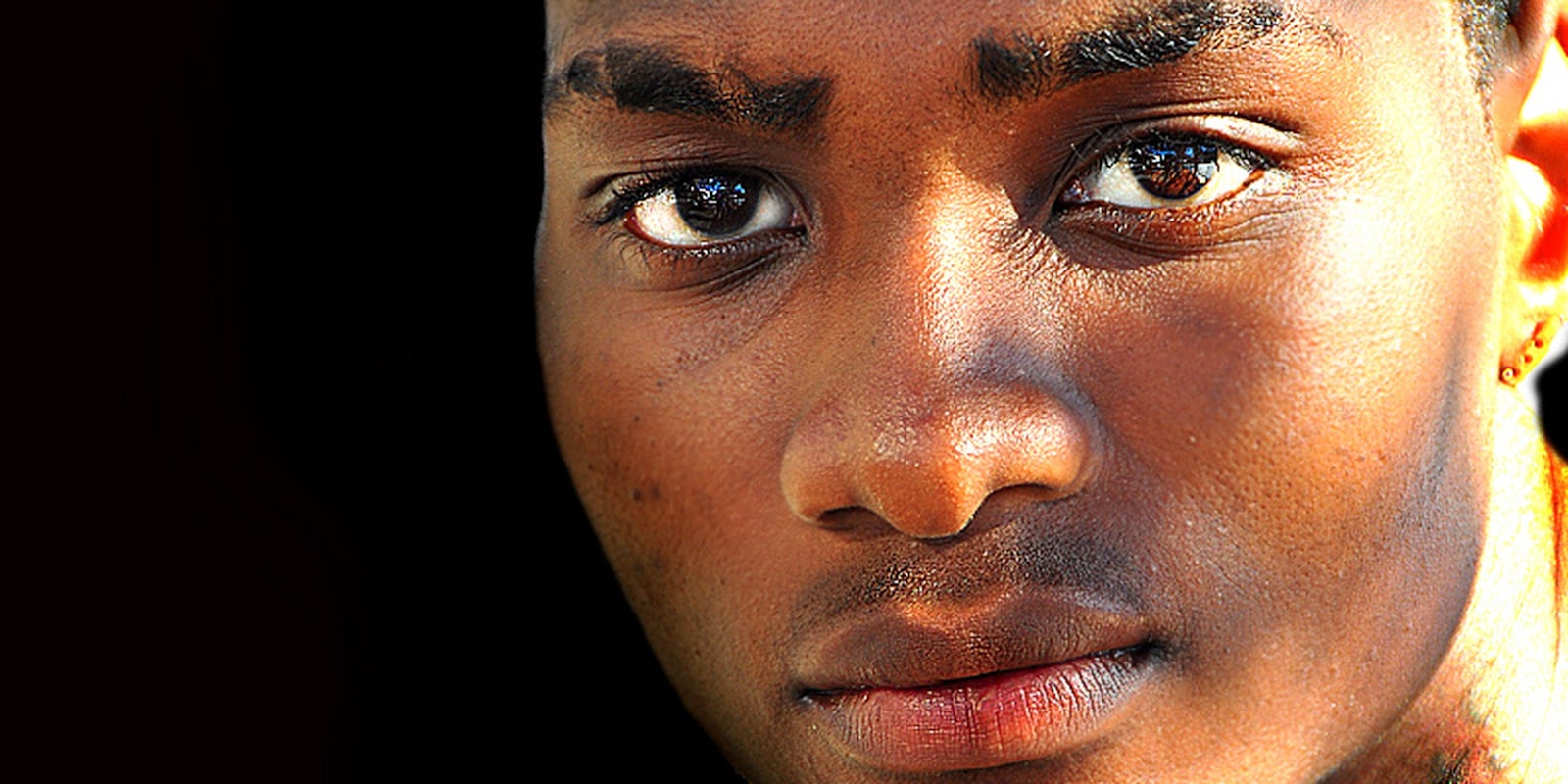

Photo via David Robert Bliwas/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)