From the presumed creators of “Obama: Muslim Lizard” and “Prometheus: Satisfying Film” comes this whopper of a conspiracy theory: Stevie Wonder is a big old faker.

Last Thursday, Deadspin writer Greg Howard decided to wade into the deep end of the pool and make the case that Stevie Wonder has been pulling the wool over our eyes for the past six decades by pretending his didn’t work. Culling together the esteemed work of WordPress blogger Bold Symmetry and sports personality Bomani Jones alongside his own research, Howard blows open potentially the biggest story this side of angry cat terrorizes family of four.

That’s not to say that these three are the only ones to have ever floated the thought into the public sphere. There’s also former NBA player Darryl Dawkins, whose nickname “Chocolate Thunder” was coined by Wonder, despite supposedly never having seen the seven-foot tall behemoth known for shattering the backboard on his dunks. How interesting.

In all fairness, Howard, Jones and pretty much any Wonder “truther” have their tongues firmly in cheek here. But it does leave behind a question with less innocuous implications: Why is Stevie Wonder not being blind all this time so funny?

There’s, of course, the simple fact that humor generally relies on subversion. What was thought up is in fact down, black is white, and a set of stairs actually a set of bees. That one of the most well-known blind people in the world turns out not to be sightless is worth a chuckle or two.

But there’s something more to it. Stevie Wonder isn’t just a blind person, he’s one of the most gifted individuals to exist in the world, a 22-time Grammy winner who is responsible for some of the most enduring contributions to the era of modern music, as well as having a long career in political activism. That he was able to do all this while never having experienced concepts like color seems almost otherworldly and humbling. And it defies our expectations of blind people.

According to the 2011 Disability Status Report authored by William Erickson, Camilla Lee, and Sarah Schrader, only 36.8 percent of those with a visual disability are currently employed, their median income lower than those of non-disabled people. While there’s certainly limitations that could prevent a blind and/or otherwise disabled person from holding onto a job, much of the difficulty with employment comes from the misaligned perceptions potential employers hold towards the blind. They’ve thought of as less punctual and less intelligent, even as the percentage of those who have obtained at least some college experience is only a shade below those without impairment.

Though there’s a wide continuum of disability, from the mental to the physical, so often the disabled are conflated onto one giant conveyor belt of incompetence. Many are the anecdotes of a blind person being yelled at as if they were hard of hearing, or being assumed to have speech difficulties. These stereotypes come packed alongside the paradoxical expectations of the disabled as fonts of inspiration. They’re lauded for their bravery yet seen incapable of the simplest tasks, more objects to be admired or pitied than fully realized people. And to break away from those easily filed away conceptions is to inspire confusion.

One of the bits of “evidence” tossed out by Howard is Wonder’s frequent presence at basketball games, front and center, sunglasses and all. Leaving aside the very obvious screengrabs of a headset which Wonder presumably uses to keep track of the game (or the fact that the front row seats are both for him and his children), the joke is that it’s suspicious by its very nature that he could enjoy the sport every bit as well as a sighted man could.

The same goes for Wonder at one point wanting to take part in Dancing with the Stars. Or that he could play pranks on people when he was younger, despite having his condition nearly since birth. The joke (and to reiterate, no one here is making a serious case) only works because blind people shouldn’t be able to enjoy sports or goof around like us normals can. Ergo, Stevie’s a fakie. Ha-ha.

It also speaks to the reality that disabled people are often forced to prove their disability to the world, lest we revoke away our obligatory sympathy.

Earlier this September, singer-songwriter Kanye West berated two members of the audience for not standing up during his performance, despite being told they were disabled. Only after having his staff visually check for a wheelchair did Kanye finally continue on with the show.

In August, George Takei (of Star Trek and Internet fame) passed along an already popular meme on his Twitter account mocking a wheelchair-bound woman who was shown standing up as she reached for a bottle of liquor. Plenty of others who carry less visible disabilities are used to death stares as they dare to saunter into a handicapped parking space or advocate for better building accessibility without appearing nearly immobile. Like Wonder, the image of a disabled person not being as helpless as we caricatured them out to be is a source of suspicion and derision.

To be clear, I’m not trying to pick on the Wonder truthers, who unlike the previous examples, aren’t coming from any place of malice. And Howard’s article is hilarious in presenting its building blocks of proof, even if they’re as solid as my little nephew’s Playdoh set.

For instance, Dawkins’s supposed belief that Wonder isn’t blind is taken from a tongue-in-cheek chat with the TMZ crew this summer. In an earlier interview in 2011, Dawkins offhandedly mentions that it was Wonder’s assistant who first pointed him out to the singer, aptly describing him and his booming dunks to Stevie. (And yes, I seriously spent time researching and debunking that claim.)

But humor doesn’t come in a vacuum. The reason why we giggle at the possibility of Stevie Wonder getting a fast one on us is because it almost makes more sense than a person being able to craft such beautiful, invocative music without the gift of sight. We find it hard to believe that a blind man could be so visionary, and while that’s absolutely a credit to Wonder’s long, prosperous career, it also betrays our assumptions of disability.

That’s an uncomfortable truth to realize, sure. But it’s definitely better than being a sheeple beholden to the interests of Big Lenscrafters.

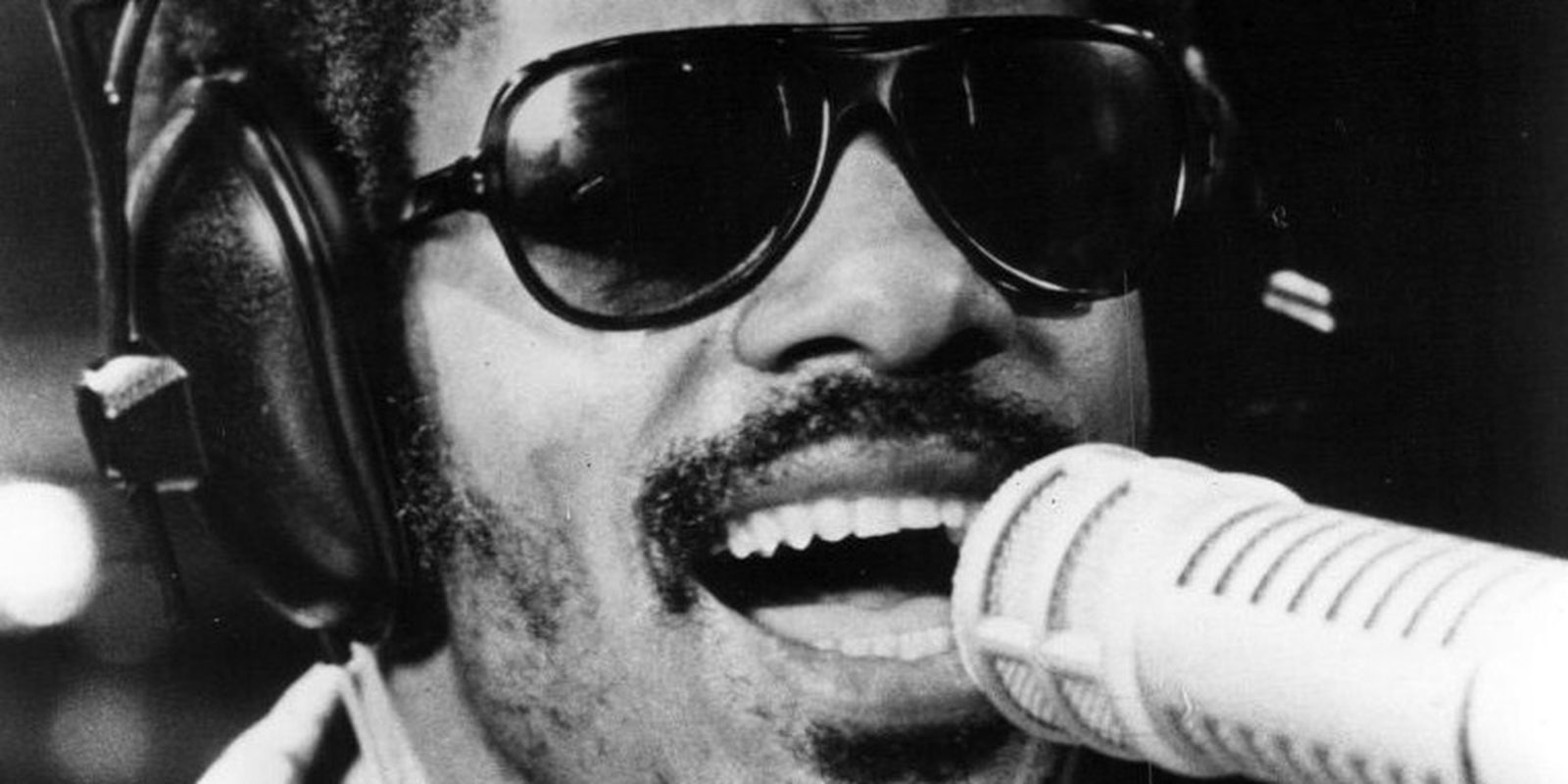

Photo via We hope/Wikimedia Commons