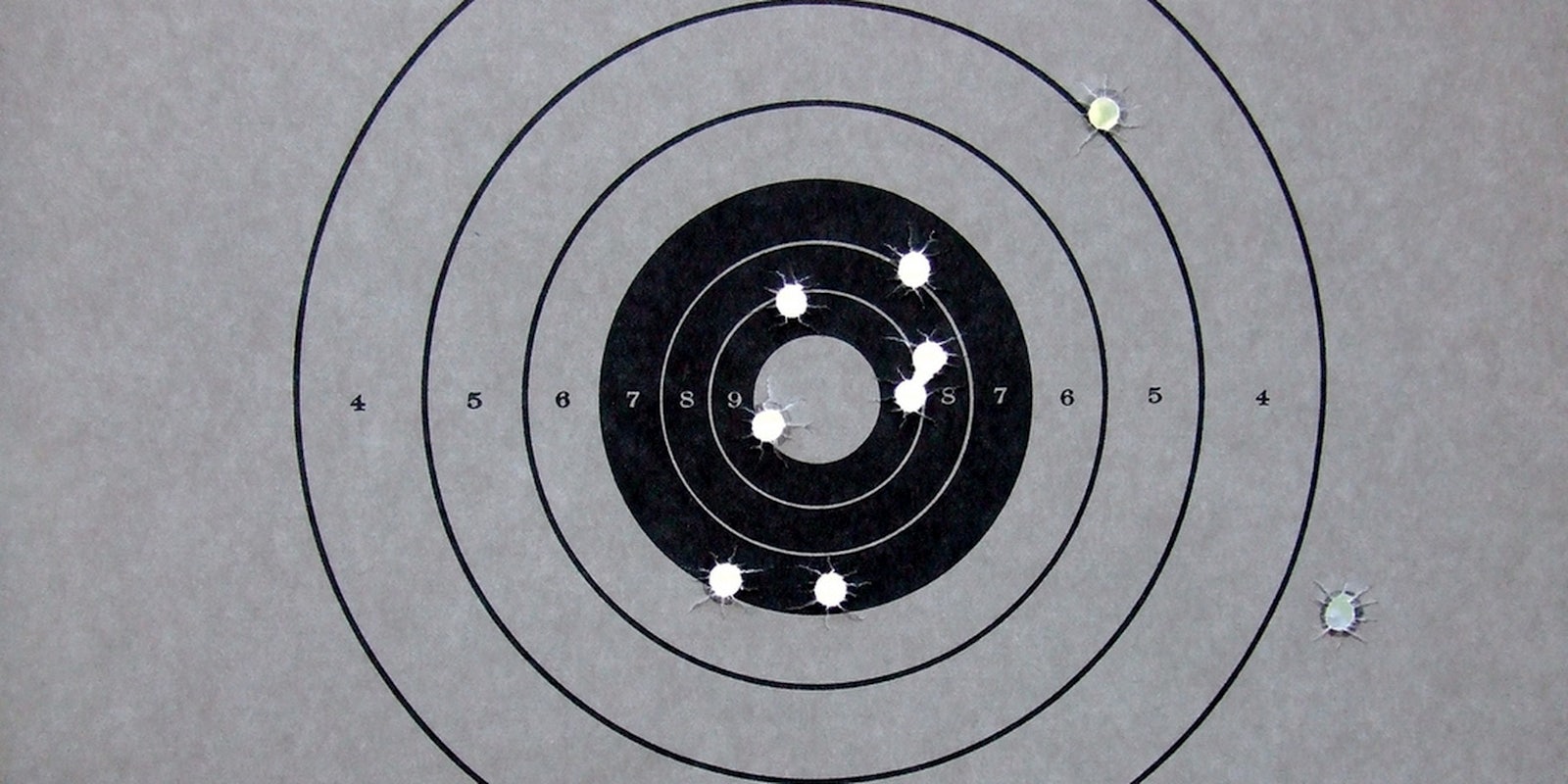

North Miami Beach police recently scrambled to pass a new ban on officers using pictures of civilians as target practice. Whether or not to ban the practice apparently prompted heated debate (though why this wasn’t a no-brainer is baffling), but it was permanently banned after Army Sergeant Valerie Deant came across photos of her own brother among the images used for police target practice. Since the use of the targets was exposed, there has been much outcry, including a campaign in which members of the clergy beseeched police officers to #UseMeInstead, tweeting photographs of themselves in their clerical clothing with messages like “Astonished @myNMBPolice use photos for targets. You do know you’re supposed to uphold the law, right? #UseMeInstead.”

This confirms what we already know about the way too many police in this country feel about black lives: They don’t matter.

The police have insisted that they’ve done nothing wrong, dismissing accusations of racism and contending that “minority officers” were among the police who used the photos as target practice. I guess even officers of the law aren’t above using the “my black friend says it’s OK” line.

But all these justifications aside, this serves to further confirm what we already know about the way too many police in this country feel about black lives: They don’t matter.

#BlackLivesMatter has been the target of many a troll, both online and off, and has been a central concept in the protests that have soldiered on since Officer Darren Wilson killed unarmed black teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. The tone-deaf counter-slogan #AllLivesMatter has been taken up by those who are (for whatever reason) unwilling to acknowledge the specific struggle of black Americans for humanity. As Judith Butler writes for the New York Times:

When we are taking about racism, and anti-black racism in the United States, we have to remember that under slavery black lives were considered only a fraction of a human life, so the prevailing way of valuing lives assumed that some lives mattered more, were more human, more worthy, more deserving of life and freedom, where freedom meant minimally the freedom to move and thrive without being subjected to coercive force.

But when and where did black lives ever really get free of coercive force? One reason the chant ‘Black Lives Matter’ is so important is that it states the obvious but the obvious has not yet been historically realized. So it is a statement of outrage and a demand for equality, for the right to live free of constraint, but also a chant that links the history of slavery, of debt peonage, segregation, and a prison system geared toward the containment, neutralization and degradation of black lives, but also a police system that more and more easily and often can take away a black life in a flash all because some officer perceives a threat.

I expect the #AllLivesMatter insisters will rise up again as the police of North Miami Beach assert that their shooting range targets include whites as well. But even if this is true, we must stop and remember something very important: Generalizations about white people do not get white people killed, nor does it prompt their mass incarceration. If you’re black in America, stereotypes literally kill.

If you’re black in America, stereotypes literally kill.

Black faces as shooting range targets—some with bullet holes through their foreheads and eyes—stings particularly painfully when, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, a white police officer used deadly force against a black person almost two times a week between 2005-2012. Police officers like Darren Wilson and wannabes like George Zimmerman often use the “I feared for my life” defense when attempting to justify the shooting and killing of unarmed black kids. We all remember Zimmerman—a trained MMA fighter—claiming that 17-year old Trayvon Martin overpowered him, forcing Zimmerman to use his weapon, and more recently, Darren Wilson—6’4” and 210 pounds—testified that he “felt like a five-year-old holding Hulk Hogan” in regards to his encounter with Michael Brown, calling Brown a “demon” and an “it.” Wilson’s testimony especially exposes something particularly disturbing about the way white people (even police) perceive black bodies—as dangerous, evil, inhuman—and what that means for the safety of black lives.

Research backs this up. In a study carried out by the University of California, research showed that dehumanization of black people led to increased violence (trigger warning for racist imagery):

[Police officers] who compared blacks to apes were seen as having a higher level of dehumanization. Researchers compared … officers’ personal records against their levels of dehumanization towards blacks. They found that officers who had higher levels of dehumanization towards blacks were more likely of having a history of using force against black children in custody, than those who did not dehumanize blacks. Use of force was defined for the purposes of the study as instances of an officer using a takedown or wristlock; kicking or punching; striking with a blunt instrument using a police dog, restraints or hobbling; or using tear gas, electric shock or killing. Surprisingly, only dehumanization was found to increase a police officer’s use of force against blacks. Both conscious and unconscious prejudice did not have any link to the likelihood of police officers using violent force against black children in custody.

Other studies show that civilians and police officers alike are less likely to view black children as innocent, and more likely to perceive black children as older than they are. Indeed, the police officer who shot and killed 12-year old Tamir Rice in Ohio claimed that he believed Rice to be 20 years old. If you’ve seen photos of Tamir Rice, it’s plain to see that it wasn’t the boy’s features that painted this picture of age and maturity; rather, it was the officer’s bias, the same bias that led him to kill Rice for carrying a BB gun, despite being in an open-carry state.

This week’s headline story of award-winning New York Times columnist Charles Blow’s son—a student at Yale—being accosted by police with drawn guns further illustrates the heartbreaking truth that respectability politics won’t save black lives: Just as wearing a suit did not keep Martin Luther King, Jr. from being assassinated, being a student at Yale does not protect black Americans from being harassed and assaulted.

A study revealed that cars are twice as likely not to yield for black pedestrians crossing in a clearly marked crosswalk.

Just last week, 62-year-old black grandfather and legal gun owner Clarence Daniels was shopping at Walmart when he was tackled, restrained, and put in a chokehold by three white men who saw his legally concealed firearm and suspected him of being a criminal—while he shopped for coffee creamer. Even pedestrians crossing the street are subject to racial bias: A study revealed that cars are twice as likely not to yield for black pedestrians crossing in a clearly marked crosswalk. Respectability is worthless—student, grandfather, law-abiding citizen—when there is active (and violent) racial bias.

The thing is, the North Miami Beach police aren’t the only ones using black faces as target practice. Fear of blackness is reinforced by mass media, in which white killers are portrayed more sympathetically than black victims; in which black men are continually portrayed as violent, one-dimensional gangsters; and in which black women are still vastly underrepresented in roles outside servants or dangerous, angry “ghetto girls.” It’s why when white people commit a crime but try to pin it on someone else they often choose a black scapegoat—and why they’re so often believed. We’re part of a culture that demonizes and vilifies black people as young as 10 years old.

Actor Jesse Williams has taken to Twitter and television to speak about police brutality and the way it targets black Americans, extending the conversation into the representation of minorities in media and the harm it does when those representations are dehumanizing:

There is certainly a double standard of Whiteness and a bit of an ownership mentality in this country that rears its ugly head when we get into crime or incidents that happen that involve Brown people. Victims of these shootings are immediately vilified on screen and in the media and the online networks, trying to justify putting these boys on trial for their own murder and they are always found guilty of their own murder. And we don’t feel that that’s what happens when white people shoot up schools or theaters. They are immediately just trying to be explained, get to the bottom of it, and interview people around them. Find out what happened. It feels imbalanced, because it is imbalanced. There is a disproportionate representation of low income Black folks in media. … All these things create an imbalance.

We should remember this demonization of black people—whether young or old, male or female—when police take the lives of unarmed civilians: The police, like all of us, have been born and bred on a media culture that feeds us the myth of White Heroes and Black Thugs. With testimonies like that of George Zimmerman and Darren Wilson, Americans are persuaded to believe that it’s scary being a cop (or a neighborhood watchman) and scary being face-to-face with black men. But what are we supposed to believe when police officers are caught using pictures of black men as target practice in the shooting range? That doesn’t sound like fear: It sounds like hate. It sounds like the ideological construction of an enemy. The North Miami Beach officers have also claimed to have photos of Osama bin Laden in the range as a target. Is this how officers are molding their vision of the civilians they are sworn to protect? By equating them with terrorists?

That doesn’t sound like fear: It sounds like hate.

A recent study found that police officers come out of the police academy already having a bias toward use of force, and that there is alarming correlation between race and perceived threat. But what of police who thrill themselves with this perception of threat? Literally training their eye in the shooting range to see a black face and shoot? Is it really fear triggering the gun, or is it the result of a well-practiced drill?

Like in the Implicit Association Test, in which the test taker must quickly choose whether to apply “bad” and “good” words to black or white people (pain, joy, horrible, pleasure) in the blink of an eye, in which all our prejudices are tested, perhaps police like those in North Miami Beach are underestimating what they teach their own brains when they tape up pictures of black boys to gun down. What it comes down to is that we are supposed to believe police officers’ fear because we are supposed to believe that people with black skin are to be feared. We are sold the officers’ fear and convinced to ignore the fear of being black in America, born with a target painted on one’s face.

We are sold the officers’ fear and convinced to ignore the fear of being black in America, born with a target painted on one’s face.

You’re reading this, and perhaps you’re asking yourself, “Who is we?” “We” is certainly white people: We whose thoughts of crime and danger are triggered at the mere sight of a black man, and we who are more likely to advocate for punitive laws if the population being punished is black. However, that “we” is not limited to white people: The message that black folks are “bad” and deserve what they get is swallowed by black children, who even now 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education, when presented with a black doll and a white doll and asked to indicate which doll is “bad,” choose the black doll. Jesse Williams said, “Violence takes; it steals immeasurably.”

He’s right. Using black faces as target practice not only sets the stage for the further loss—no, theft—of black life, but it steals something else too: humanity. When we say #BlackLivesMatter, we can’t only be referring to the right to safety from state-sanctioned murder. We must also mean safety of the spirit. Allowed to cross the street. Free to buy coffee creamer. Free to be a student. Free to be children. We must also mean that black lives deserve to be whole, healthy, and human.

Black lives matter. We must say it until our throats are hoarse. The alternative is what? Silence? When we’re talking about the killing of human beings, silence is consent. Silence is unacceptable.

Photo via bitmask/Flickr (CC BY-S.A. 2.0)