Comedy is one of my big loves. I love it for the belly-aching, tears-rolling-down my face laughter it induces. I love it for the escape it provides from a particularly stressful day, week, or even year. But I also love it for its depth. At its best, I believe comedy is a tool for facilitating connection and heightening awareness that can lead to social change. I believe comedy is powerful stuff.

As a comedian, a writer, and a person of mixed heritage, I read Jazmine Hughes “How Many White People Does It Take to Ruin a Good Joke?” on New Republic with vested interest. I was excited that Hughes (who is also a contributor at the Daily Dot) was opening a dialogue about comedy, privilege, and self-awareness. I’ve been to open mics and cringed at jokes that lacked awareness, and I’ve watched some of my heroes give shows that made my heart soar with hope that comedy can lead to deep, meaningful understandings across race, class, and gender lines.

I was perplexed, however, by Hughes’ bottom line, which is this: White people should not make jokes about white people. According to Hughes, when they do, they’re usually unfunny and they reinforce white privilege. In effect, white people who choose to mock white people are crashing the party, and once they do, the party is over.

But what most white-people jokes have in common is that they are not about white people per se. Instead, they are about inequalities between whites and other races. “What is the scariest thing about a white person in prison?” a comedian asks. “You know he did it.” Har har! Except you only got the punchline because you’re aware of the problem of prejudicial prosecutions. In sum: “LOL, RACISM.”

In rarer cases where white people are the actual target, the joke tends to zoom in on a certain sector of the population—hippies, rednecks, anyone who is both white and poor—and rests on observations about socioeconomic circumstances, not the disadvantages posed merely by having a certain color skin. So when a white person tells any white-people joke, the humor can go from subverting whites’ status to rubbing it in. The jokes themselves aren’t necessarily less funny; it’s just that the bitter pill goes down easier when not delivered by someone benefiting from the privilege they’re trying to lampoon.

It’s true that the specific examples Hughes shares are off-putting. Hughes references several jokes found on Twitter and Tumblr that begin with “White people be like…” Although Hughes feels differently, these jokes are frequently made by people of color, in the comedic spirit of “punching up”—they take the people on top down a few notches and offer comedic relief from the ugliness of our social reality. As Hughes points out, however, these jokes are a bit more troubling when made by white people who want to “get in” on the fun.

Hughes argues that when white people chime in on Twitter, Tumblr, or other forms of social media, they’re co-opting a joke from a non-white culture and “gentrifying” racial humor. I would absolutely agree. If they’re using that specific language, “white people be like” they most definitely are.

A white person adopting black vernacular to make an observation about how silly white people are is akin to trying to fist-bump a black friend, or calling him “brother” to “in” yourself. The white joke-teller is letting the larger audience know that he or she “gets” what it’s like to see white people from a black person’s point of view.

This notion is presumptuous and the reality of it is impossible. A white person cannot know or report on this experience because a white person cannot experience it. Hughes wisely remarks that something is off when white people try to be “cool” by mocking white people from this assumed perspective.

Her broader argument, however, that white people cannot and should not make fun of white people (unless, of course, they happen to be Louis C.K.) leaves much to be discussed. The idea that a white person cannot share in the laughter, and cannot point out their own role in an unjust system, limits the possibility of meaningful dialogue. When we limit opportunities for dialogue, we limit opportunities for mutual understanding and at the very worst, we may be closing off the very communication lines necessary for meaningful social change.

While there are absolutely too many white people who still don’t understand the mechanics of privilege, the fact that mainstream white people finally want to be a part of the conversation is a good thing.

Hughes cites a particularly insightful joke from Louis C.K. in which he highlights his own access to privilege as an exceptional anomaly, when the reality is that there is a long history of professional comedians, of diverse backgrounds, who have laughed about race—and white privilege in particular—with remarkable success.

George Carlin, for example, predates Louis C.K. by decades with his cutting criticism of white people trying to latch on to black culture: “White people got no business playing the blues at all, under any circumstances, ever, ever, ever. What the fuck do white people have to be blue about? Banana Republic ran out of khakis? The espresso machine is jammed? Hootie and the Blowfish are breaking up? White people ought to understand their job is to give people the blues, not to get them.” Jokes like this pique social awareness, but what makes them particularly subversive is that they invite both the privileged and the oppressed to share in the laughter.

Hughes also cites Eddie Murphy’s unforgettable 1984 Saturday Night Live sketch “White Like Me,” in which he donned white face and discovered the elaborate depths of white privilege. But she fails to recognize that he did so with the support of white allies and a white audience, which is part of what made the sketch so memorable and so exciting. It’s not that the joke belongs to white people, it’s that when a diverse audience laughs together we build trust, intimacy, and room for a space to air grievances without threat or fear of retaliation. These opportunities are rare, and the capacity of comedians to access them is valuable for our society as a whole.

Even in academic spheres, comedy is gaining recognition as a tool for challenging stereotypes and facilitating the deeper thinking and awareness necessary to foster social change. In “Thinking Twice: Uses of Comedy to Challenge Islamophobic Stereotypes,” Zara Maria Zimbardo advocates for the use of comedy in the undergraduate classroom as a pre-curriculum for “sophisticated facilitators who are immersed in antioppression curriculum and antiracism work in particular, [who frequently] ‘hit a wall’ when it comes to Islamophobia.”

Zimbardo quotes historian of humor Joseph Boskin, who observes, “Just as humor has been used as a weapon of insult and intimidation by dominant groups, so it has been used as a weapon for resistance and retaliation by minorities.” If the culture of power has chosen to participate in the joke, is that a sign of danger or progress? Does that tell us that the people in power are trying to maintain power, or does that tell us that they are listening and engaged?

Comedy is subversive and powerful, and it’s at its most powerful when it is consumed by a diverse audience.

Comedy is subversive and powerful, and it’s at its most powerful when it is consumed by a diverse audience. When an oppressed group laughs in private, comedy provides relief and may empower and embolden the oppressed, but jokes become even more impactful when the culture of power is alert, listening, and open to a dialogue. After all, Zimbardo’s paper is not about how to get Muslim students to realize they are oppressed. The oppressed already know all too well the reality of these injustices. The aim here is to get the people who are on top, those who have nothing to lose, to make themselves vulnerable enough so that a change in awareness occurs and so that real growth may take place.

In an effort to trace the origins of white-on-white jokes, Hughes mentions the blog turned book, Stuff White People Like, a comprehensive list of things white people adore written with an anthropolgical tone. Stuff White People Like was funny because of its specifics (#51 is Living by the Water), but I doubt anyone would point to it as an impetus for social change. At the very least, it signified the willingness of white liberals to laugh at the misgivings of other white liberals who, while well-meaning, fail to recognize their privilege and their imperfections.

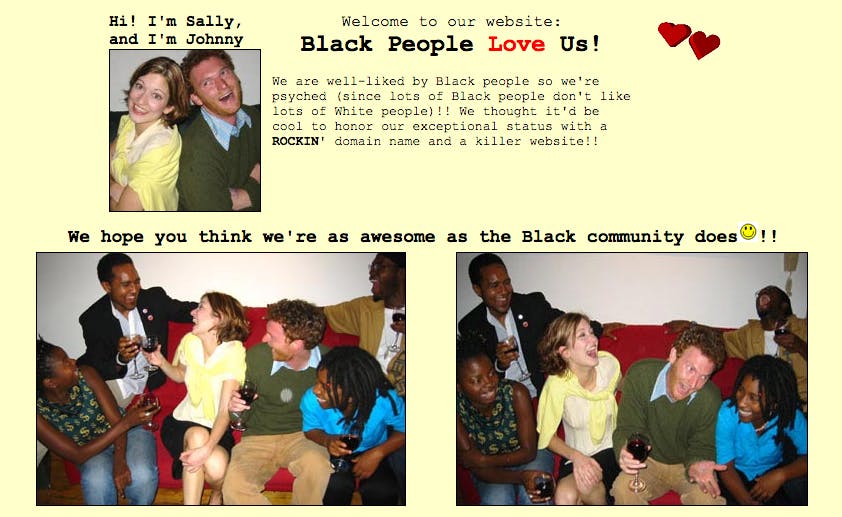

Hughes points to the blog as an “ur-text” for “white-on-white racial humor” but it was actually preceded by “Black People Love Us,” a terrifically conceived, and far more socially-aware site, created by siblings Chelsea “One of the Greats” Peretti and Jonah Peretti (the Founder of BuzzFeed) . The site portrays a fictional white couple, Sally and Johnny, and features their many misguided attempts to relate to their black “friends.”

The site cleverly pokes fun at self-appointed allies by revealing how easily and how often they reinforce stereotypes and reassert their dominance over oppressed groups. In celebrating their “friendships”, Sally and Johnny seem to be perpetually congratulating themselves. “We did it, we’re terrific,” they seem to say. “We’ve really beaten racism! Can you believe how fantastic we are?” Meanwhile, the pictured black friends cast various degrees of side-eye indicating the full awareness of the site’s creators that the joke is on the glib white liberal “champions of progress” embodied by Sally and Johnny.

Another example of on-the-mark white-on-white humor is the interminably irreverent Stephen Colbert. In recent years, Colbert has perfected the art of attacking the privileged white male, by casting himself as an oppressed, downtrodden conservative in need of allies. As the host of Comedy Central’s The Colbert Report, he satirically advocated for the rights of the white male, and even wrote a “Guide to White Male Oppression” for men’s magazine Esquire. In it, he recounts the history of male oppression, which climaxes with this delightfully absurdist remark: “Then came one of the darkest chapters in American history: the Space Race, when our government launched a sinister conspiracy whose sole purpose was to shoot all white men into space.”

Colbert’s perfection of satire takes white-on-white humor to the very limit by highlighting the absurdity of privilege. He is brilliantly self-aware, subversive, and cutting. Is he co-opting a joke? Or is he creatively contributing to a larger, more important dialogue?

If we’re going to effect real social change through comedy we should absolutely cast a critical eye on racially-charged jokes. In her article, Hughes quotes comedian and improviser Keisha Zollar of the Upright Citizen’s Brigade theater, whose screen credits include Orange is the New Black and Broad City, to explore the larger theme of whether white people are capable of responsibly mocking other white people.

All of which is to say that the teller of white-people jokes bears a special responsibility. White-people jokes don’t punch up; at best, they punch sideways, but usually, they punch down. This doesn’t mean that white people can never tell them. But I do believe that anyone who tells a white-person joke really has to understand what they’re doing. “Jokes have power to be tools to dismantle oppression, to prove racism, but also to reinforce racism and privilege,” says Keisha Zollar, an African American comedian with the Upright Citizens Brigade. “Is the comedian telling the joke aware of that power?”

Zollar has made it her personal mission to engage people from diverse backgrounds in conversations about race and privilege. Her ongoing project and live performance An Uncomfortable Conversation About Race is a unique social justice experiment incorporating comedic game show sketches like “The Newly Friends Game” and “Reverse Racism Jeopardy,” round table discussions, and even a personal one-on-one dialogue with her white husband while in bed, in front of a live audience.

I attended the first installment of the show in December, and was struck by the warmth and candor of the event. One exchange between Zollar and fellow comedian Megan Sass exemplified the complications of participating in an “uncomfortable” dialogue.

Sass stated that she felt uncomfortable using the hashtag #blacklivesmatter because she did not want to speak for black people not having experienced any of the suffering related to the hashtag firsthand. Zollar urged Sass to be a part of the conversation because she felt people needed to speak across lines of race and privilege for real change to occur. But Zollar never spoke from a place of imperatives. Instead, she really listened to Sass and heard her out. In this way, Zollar didn’t tell Sass how to be an ally, she showed her.

When I asked Zollar about her vision for the project, and her reasoning behind bringing so many diverse voices to the discussion she told me, “Everybody knows how to talk comfortably about race. What I care about is a slight discomfort where growth can happen—being open to being wrong.”

Zollar hopes that, armed with humor, people of diverse backgrounds can muster the courage to get uncomfortable and achieve true change and growth. She also has a refreshingly goofy take on what social justice might look like.

Why does social justice have to be so serious all the time? I feel like everybody needs to put on a suit and tie when they talk about race [and] the comedian in me is like, hey, no, because race and conversations about race can’t just belong to the academics, to one sphere. It has to belong everywhere. I laugh at myself all the time—I’m a ridiculous meat suit and in my mind. … I’m an existentialist, nihilistic Oprah and what I want to deliver instead of you’ve got a car, you’ve got a car, is you’re gonna die, you’re gonna die, so let’s stop being awful to each other.

This is an exciting time for comedy and an urgent one for our society. With all of the recent unrest and injustice following the deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and the subsequent judicial decisions not to hold their killers accountable, our society is aching and crying out for change. Change can be frightening, overwhelming, and unwieldy, and what better ally than humor to help us through it?

The most recent example of the kind of humor that speaks to this dialogue came on last week’s episode of the famously irreverent Broad City. Ilana (Ilana Glazer) and her mother (Susie Essman) are arrested by the police when it mistakenly appears they are hawking knockoff bags on a city street corner. The mother-daughter duo incessantly berate the officers from the back of their police car. To put it mildly, they are on their worst behavior. The two hurl barely decipherable insults, culminating in Ilana’s mother snarling, “Boy prostitutes!” When the officers do finally release them, Ilana scoffs, “I guess we’re being let off easy because we’re extremely white.” Her mother adds, “Yeah, that’s the prison industrial complex for you.”

Indeed, comedy can raise awareness, deepen connections, and forge alliances. So if we want to dismantle the hegemony, we may need to start by laughing at it, together.

Photo via flippey/Flickr (CC BY-N.D. 2.0)