When I got a story pitch saying that a certain hotshot orthopedic surgeon had decided to livetweet his surgery, frankly, I thought: He’s insane.

It’s unethical, right? Is he going to stop paying attention to the patient and turn to his Twitter feed—while he’s operating?

How would that even work, medically? Does he put the instruments down first? Re-sterilize after tweeting? Have a nurse hold the phone up for him to dictate?

Is this a tipping point? For God’s sake, do we really have to tweet everything?

You already know I’m an ardent social media fan. I love sharing my own foibles online. I even wrote about my own knee surgery, inviting a photographer into the bloody scene (I don’t think he’s forgiven me yet). So it’s not like I’m opposed to putting stuff out there. But isn’t this going too far?

Of course, I was a little emotional when I got this pitch—it hit home with a punch. When I received it, I was sitting in my mother’s hospital room as she was recovering from some pretty major back surgery.

So it felt personal. The last thing in the world that I’d want would be my mom’s surgeon making some mistake because he was focused more on a clever hashtag than he was on his scalpel.

I immediately started asking the doctors and nurses and other healthcare professionals who were coming in and out of the room what they thought. When I told one nurse, who was standing at the computer filling in my mother’s chart, her eyes grew big. “That’s totally unethical,” she said. That was pretty much the universal response.

So when I got on the phone with Dr. Derek Ochiai, the orthopedic hip arthroscopic surgeon and sports medicine expert, in Arlington Virginia, I came armed with pointed questions.

First of all, why did he decide to live tweet the surgery?

“I thought it would be a way of educating in a real-time way medical students and basically anyone who wanted to learn about hip surgery,” he told me.

“I also thought it might be a way to mentor younger students—to get them interested and excited about orthopedics as a possible career path.”

OK, sounds reasonable so far; Ochiai wanted to show people what it was like to be a surgeon who has to make decisions once he opens up a body.

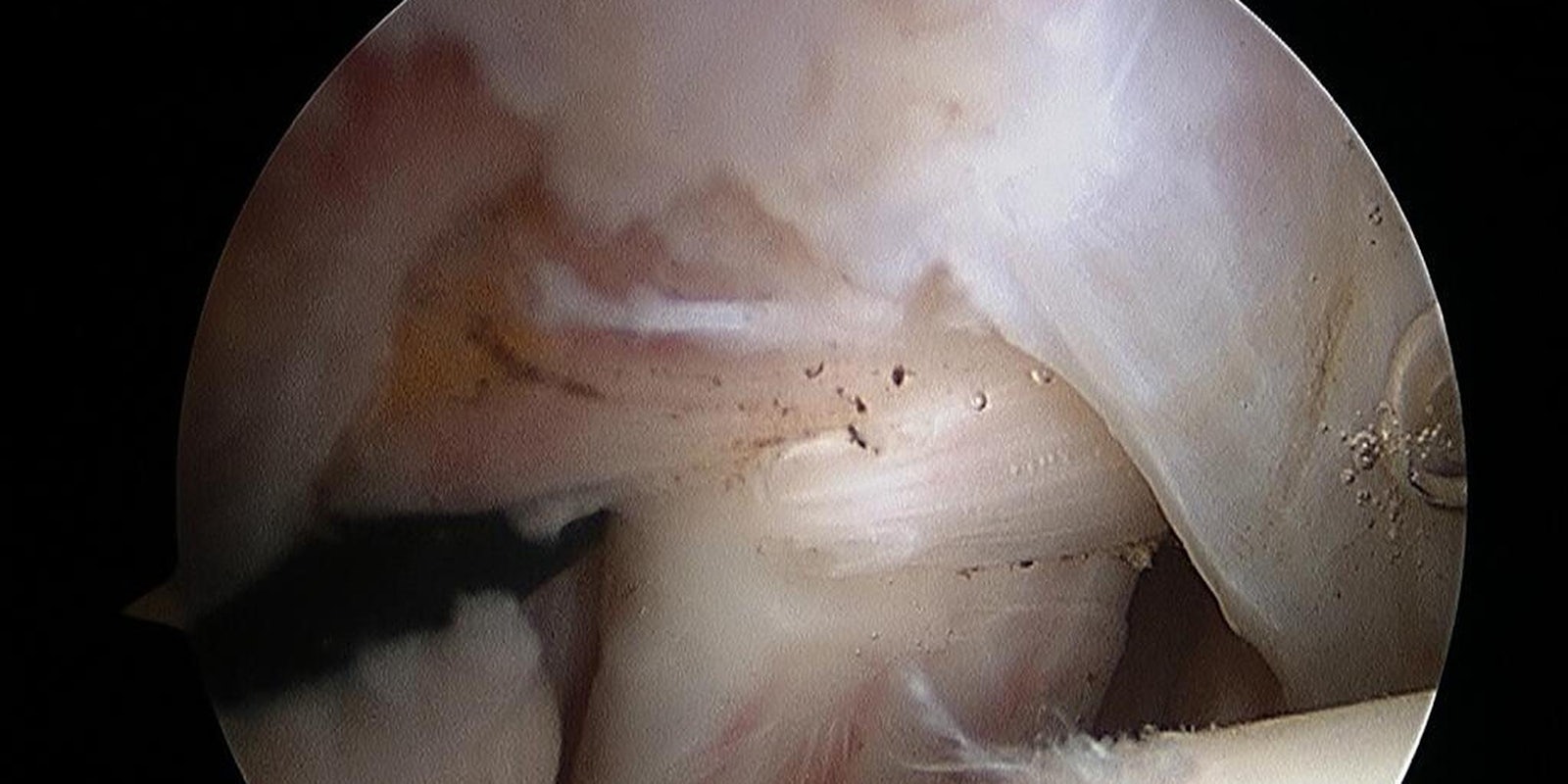

I’ve had several knee arthroscopies myself, so I knew he’s right about how real-time surgery goes: X-rays and MRIs only tell you so much. The surgeons really don’t know what they’ve got in front of them until they take a peek at the actual surface of your bones. It’s pretty interesting stuff.

It could be the future of medicine, Ochiai pointed out. Surgeons already show each other videos of their surgeries; usually they are narrated and shown on a private orthopedic surgery channel. But the videos are posted after the surgery. This surgery was real time. You see what the surgeon saw, when he saw it. And if the surgeon made a bad decision, you’d see that too.

All good points, I thought. And actually, kind of brave. How would you like it if the world stood over your shoulder and watched you as you did your job?

But still—the privacy violations! And seriously, livetweeting actual surgery? Isn’t it going a bit too far? I couldn’t help myself.

“I have to confess,” I told the doctor, starting my line of questioning about the inherent problems with livetweeting, “one of my reactions was, ‘Wait a second. So the surgeon’s going to be paying attention to Twitter? So was that a concern at all, you know that you’re going to be paying..’”

“Well,” he said, cutting off the rest of my sentence (mercifully), “It’s a cadaver lab. So it’s a teaching lab.”

Ooooooooooooooh. Facepalm. I missed that one, very key word in the pitch (remember, my mom was in the hospital, so cut me some slack). A dead person. Well, that clearly does change things. Dead people don’t need anesthesia. If they’ve donated their bodies to science, they don’t need to approve the surgery. Most of the cadaver doesn’t even need to be there—just the hip.

So all those niggling questions? Gone.

And now that I wasn’t outraged anymore, I thought about it even more.

My mom has a lot of friends. I mean like an entire fan club of friends. What if they’d all been able to get live updates, too? As it was I was their main proxy: sending live text updates to them and family members and anyone else who wanted to know how it was going.

Wouldn’t they all have appreciated being updated by the surgeon directly, maybe almost as much as I had? Maybe more?

And that’s not even thinking about the young kid who could learn about spines and become a better surgeon because of this.

How would I have felt if the surgeon worked it out with the nurses and obviously the patient? What if he had tweeted out a picture of her spine and another surgeon in Australia chimed in and saw something her surgeon didn’t? Online collaboration can save lives—solving rare medical mysteries, and advancing research.

It’s an interesting idea. The more I think about it, the more I think it’s inevitable. Of course this will be the future of medicine. It’s the future of everything else, right?

I asked Ochiai what he thought about taking it to that level, engaging in sharing while conducting live surgery—on live people.

There is, he said, “potential for real-time interactive forms while things are going on.”

With medical education being as expensive as it is, online learning is becoming increasingly important part of education, Ochiai said. It could prove to be very useful indeed.

Ochiai doesn’t have any immediate plans to livetweet operations on live people, but he wouldn’t rule it out either.

And I suppose after thinking about it, I wouldn’t rule it out myself.

Janet Kornblum writes about social networking, humans, medicine and just about everything else. Look her up sometime.

Image from Derek Ochiai/Twitter