We live in a world where people just want to see a teenage girl get hit in the head with a shovel. People also want to see Disney princesses adorned in the latest flavor of the month, animals doing atypical things, and other such content that we typically call “viral.”

The term’s origins in relation to Internet content are difficult to trace. Perhaps it developed in the mid-late 2000s Internet boom that featured such content as Chocolate Rain, David After Dentist, Charlie Bit My Finger, Leave Britney Alone, The End of the World, and others. By 2009, “viral” had entered the mainstream lexicon as a word meaning highly shared and trafficked.

But words are wind. While the sententious disquisitions about virality and musings about SEO strategy are modern constructs, pieces of content that circulate around society are not. In the past, speeches, videos, and other oddities could become as viral as possible given their time period’s infrastructure.

Even though the word “viral” wasn’t present in its current incarnation, the effects of virality were. Viral in 1990 meant a newspaper cover, a segment on television either on a news or entertainment show, and countless water-cooler discussions at offices across the nation. In 2000, it meant being circulated in AOL forwards and posted on forums and usenet groups.

Regardless of time period, all viral things shared something in common: they were all departures from the mundane and the expected. They were so ridiculous, or joyous, or funny, or otherwise elicited such strong emotions that they had to be shared. In the era before BuzzFeed and Upworthy, virality was the exception, not the rule.

Alas, viral content has become a lucrative business. It didn’t take long for companies to realize our yearning for the atypical could be exploited for financial gain. Web culture, and the very concept of virality along with it, has been undergoing digital gentrification ever since.

Let’s look back to September 2013. A girl put on her iPod and started shaking her ass in rhythmic motions—twerking, as it’s called. She did a handstand and twerked while using the door to her apartment as a fulcrum. Disaster struck moments later. Her roommate opened the door, sending the twerker plummeting onto a coffee table cluttered with candles. The twerker’s yoga pants caught fire. She screamed. The video ended. A mega-viral sensation was born.

And a week later it was killed.

“The Worst Twerk Fail EVER” was naught but commercial chicanery. After the video achieved millions of views on YouTube and coverage all over the Internet, the Jimmy Kimmel show revealed it had all been a hoax. The show’s channel uploaded an extended video in which Kimmel himself put out the fire, making sure to bear his snarkiest “made you click” grin.

This past March, a video of strangers kissing for the first time wowed the web. The video displayed raw human emotion and sexuality in gritty black and white. It also displayed how to get a maximum return on investment for advertisers. That’s right, it was an ad for Wren, an L.A.-based clothing boutique. The video only cost about $1,000 to make. To date, it has received over 80 million viewers (approximately 10 times the population of NYC, to put that number into perspective).

Fast forward to April 2014. In a rare moment of live-television spontaneity, Ellen DeGeneres grabbed a bunch of other celebrities at the Oscars and took a selfie. This fun, lighthearted moment of mega millionaires indulging a typically teenage, bourgeoisie behavior swiftly became the most retweeted tweet of all time.

However, there’s no such thing as a jovial, spur of the moment idea when brands rear their disgusting, bloated heads. The Oscar selfie was a corporate ruse developed by Samsung, arguably the most pervasive instance of product placement in human history. The advertising firm responsible for the idea behind the photo values the selfie at approximately one billion dollars.

Perhaps duplicity is expected from such markets, but even something as niche as “Weird Twitter” isn’t free from falsehoods. Famed and beloved weird Twitter account @Horse_ebooks—a supposed spambot that unintentionally waxed philosophic—was a fake. It was the brainchild of a not so nice advertising mogul. The goal: shilling an interactive video game.

If something is viral in modern times, it’s often either a hoax, an advertisement, or—in the case of the Internet’s “viral” lists and articles—the result of a carefully crafted process.

There’s proof of this, as The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson argued in an examination of the stark future of Internet writing. He concluded that social media and the influx of analytical tools were leading to a homogenization of content.

“Why should the death of homepages give rise to the news that’s more about readers?” Thompson asked in response to the New York Times‘ home page traffic dropping by 80 million viewers in the last two years. “Because homepages reflect the values of institutions, and Facebook and Twitter reflect the interest of individual readers. These digital grazers have shown again and again that they aren’t interested in hard news, but rather entertainment, self-help, awe, and outrage dressed up at news.”

Thomson continued his assessment on what the cult of virality meant for the Internet:

Digitally native publishers are pretty good at pumping this kind of stuff out. Hence quizzes, hence animals, hence 51 Photos That Show Women Fighting Sexism Awesomely. Even serious publishing companies know that self-help and entertainment often outperform outstanding reporting.

Second, we should expect—and have already seen—an expedited clustering effect around news tropes, and this clustering is making news organizations more like each other. This goes back to technlogy. The better publishers can see what audiences are reading, the more they will be inclined to quickly serve up duplicates of the most popular stuff. This is why we have not one BuzzFeed quiz (whose popularity in the pages of a 1950s magazine would have been mysterious) but rather 17,000 quizzes in a matter of weeks from BuzzFeed, Slate, and other publishers. Each quiz’s Facebook like count, numbering in the tens of thousands, broadcasts to other publishers: I’m popular, make more of me! Even within hard news stories, we see clustering around headline tropes (“You Won’t Believe…”; “…in 1 Graph”; “X-Number Things You Y-Verb”) across many different sites that should ostensibly be serving different audiences. When you know what works, you do it again and again.

It would be absurd of me to argue that publishers never copied each other before Facebook and analytics software like Chartbeat. But today, the audience feedback loop enabled by these companies isn’t a month, or a week. We’re reading a real-time stream of audience reaction, and when we see what you like, we’re giving it to you again and again. A side-effect of this rapid- fire clustering is that media watchers become cynical of formulas (e.g. BuzzFeed quizzes; Upworthy headlines; Vox explainers) much faster than most readers even catch onto the fact that there is a formula to get sick of.

Thompson is on the right track. Just look at the Internet’s top 20 viral stories of 2013. More than half are gimmicky lists designed specifically to trend on social media. This has become standard practice. Obviously, websites want big traffic because it translates to big money. But are sharebait stories engineered by smarmy content creators in conjunction with Facebook algorithms truly viral in the traditional sense of the word?

The same question can be asked about the aforementioned hoaxes. Do these pieces of our culture truly encapsulate what virality once stood for?

Viral used to mean something novel, unusual, or outright crazy. Now viral means routine and fabricated. Modern viral content has become the antithesis of volatility. It’s just the same lists with the same images bearing the same sentiments: Remember Nickelodeon? OMG I’m 30 and therefore ancient. Jennifer Lawrence and Beyonce are so cool.

Viral in 2014 is simply a constant stream of homogenized, generic, BuzzFeed-style bullshit with the occasional gem mixed in with the turds. But once that gem is discovered, the Internet’s viral colon will be shitting out brand-sponsored duplicates within hours.

And if it’s not a list with pictures ripped from Reddit (or outright stolen from a professional), an underwhelming video with an obnoxious headline, or a data-mining quiz, then it’s another stunt brainstormed by a late night talk show intern or a marketer with a shit-eating grin.

In some ways perhaps there’s no word more apt for this kind of content than “viral.” Quizzes, videos, and lists have all become a brand-fueled pox that plagues the Internet and our senses day after day, all while we sit back, oblivious to the farce taking place, and click the Like button.

Knowing that nearly everything viral in the current age is fake—the same tired tropes trotted out day after day—perhaps we should develop a new term for the few things that are real, the few things left that encapsulate the sense of lightning being captured in a bottle the Internet rarely brings to our screens anymore.

Matt Saccaro has contrbuted to Salon, Thought Catalog, Medium, and BuzzFeed. He’s the author of the eBook, Sex, Lies, and Scantrons, as well as an eBook about U.S. diplomatic history.

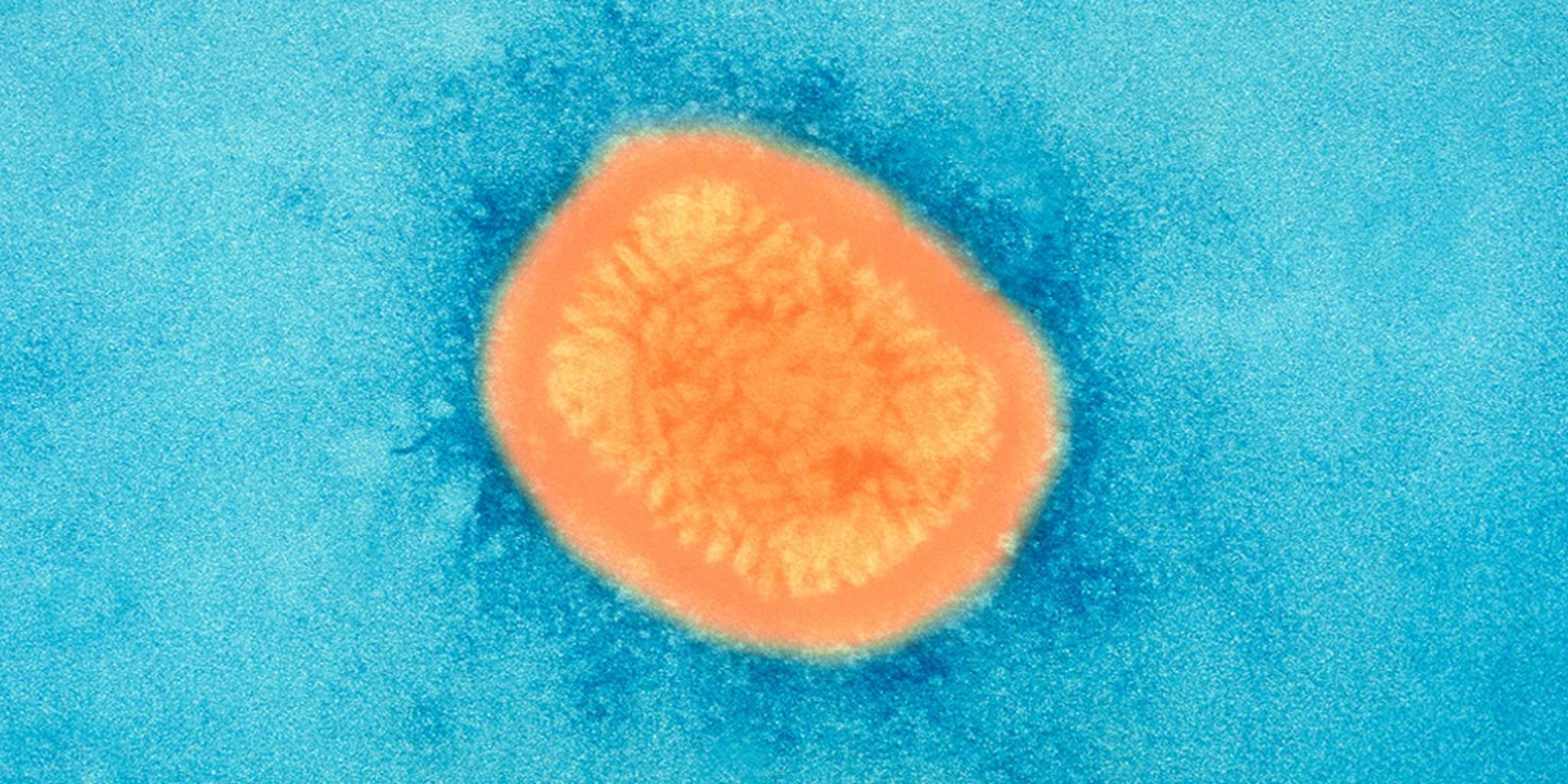

Photo via Sanofi Pasteur/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)