When he announced his campaign back in May, few thought Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) could possibly challenge an established insider like former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. But Sanders has steadily crept upward, in terms of both support and recognizability, raising large amounts of money and even making it to the cover of the very mainstream Time magazine.

The Sanders campaign should be justifiably proud of this attention and support, but it still falls short in one area—which will, if unresolved, prove to be a major stumbling block in the months ahead: his appeal to African-Americans. In August, Black Lives Matter activists interrupted his appearance at Netroots Nation, and that began a cavalcade of news coverage focused on what many have claimed are his problems with race.

But for all the attention paid to race in this presidential campaign, race is, in fact, being largely ignored in terms of any kind of substantive discussion about the issues. The intensity of the conversations, whether its in people’s social media networks or media coverage, combines with the explicit and constant reminders of violence against Black lives in particular. All of this makes it look like we are having an intense public conversation about “Race in America.”

In fact, all of this masks the fact that we’re actually evading the more crucial questions, like the links between race and economic inequality. In the process, we’re forgetting to ask the hard questions about policy decisions made by candidates. For all the chatter about race, we’re no closer to being frank and honest, because that would require frankness and honesty.

Take the race between Sanders and Clinton, for example, who are poised for their first big debate tonight on CNN. It’s Sanders’ record on race that has been much discussed, especially after #BlackLivesMatter began protesting him. But while Bernie Sanders may be an unknown quantity when it comes to race relations, we actually know Hillary’s record on the matter is terrible. None of this is likely to be addressed in the upcoming debate.

For all the chatter about race, we’re no closer to being frank and honest, because that would require frankness and honesty.

A recent Gallup poll shows Clinton’s favorability rating among African Americans at 80 percent, while Sanders’ is at 23 percent. The poll also showed that only a third of Black adults surveyed felt they were familiar enough with Sanders to have an opinion; Clinton, on the other hand, after literally decades on the national stage, was familiar to a whopping 92 percent.

Nevertheless, Hillary Clinton has an abysmal record—that is, if you consider a record on race on actual policy grounds and not just the question of visibility. Clinton’s legislative impact on people of color has been devastating, directly increasing the numbers of the disenfranchised and the economically vulnerable.

Despite this, there has—thus far—been little attention paid to her actual record. Clinton was, with her husband, effectively a co-president. This has never been a secret, with the two of them early on boasting that theirs was a two-for-one deal for the country. As such, she also bears responsibility for legislation like the North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA), welfare reform, immigration reform, and the omnibus crime bill. All of these were enacted around the same time in the mid-’90s.

Cumulatively, all of these measures devastated local economies in the Americas and beyond, causing severe hardships for poor people, particularly African Americans and women.

Research indicates that welfare reform cements racial bias toward African Americans, who are more likely to cycle back onto welfare because of the widespread lack of job infrastructure in predominantly African-American neighborhoods; research shows poor economies disproportionately affect people of color. Those workers are also discriminated against when referred to for education and training, the stated aims of so-called “welfare reform.”

The effects of welfare reform have been both devastating and long-lasting. In an October 2015 piece for Harper’s, Virginia Sole-Smith points out that “[f]or every hundred families with children that are living in poverty, 68 were able to access cash assistance before Bill Clinton’s welfare reform. By 2013, that number had fallen to 26.”

Clinton was, with her husband, effectively a co-president. This has never been a secret, with the two of them early on boasting that theirs was a two-for-one deal for the country.

Immigration reform served to create a large pool of documented and undocumented immigrants whose access to basic social services were severely slashed, making it harder for them to regain their economic footholds. It also created provisions like the “Three Strikes” laws, which increased the scope and size of the prison-industrial complex. Not only did a University of California study find that the Three Strikes law “failed to reduce crime,” it also lengthened the amount of time inmates spend in prison while increasing the overall prison population.

Clinton’s immigration reform also changed the law so that people who overstayed their visas in the U.S would now be banned from re-entry should they leave and try to return—for periods ranging from three to 10 years. This directly led to a significant number of the over 12 million undocumented in the country—given no choices and faced with being blocked from the lives they built here—staying on, reluctant to risk being barred from re-entry.

The fact that their social service benefits have been severely cut—immigration reform required hospitals to determine immigration status before treating people in non-emergency cases, for example, and denied food stamps to both undocumented and documented immigrants—has meant a worsening of their economic conditions. For the most part, immigrants most affected by the changes have been from places like Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Clinton’s record on all this has not escaped notice because people of color willfully ignore it but because the larger cultural, political, and media discourse is so preoccupied with the wrong questions. Chris Hayes, the host of MSNBC’s All In with Chris Hayes, recently asked Sanders to grade himself “on building the kind of multiracial coalition that is necessary to succeed [in] the Democratic primary deep into this contest.”

This is, of course, in one sense a fairly typical horse-race question—the kind common among journalists in electoral seasons—but it also reflects a more widespread missing of the bigger picture. It’s unclear what is meant by a “multiracial coalition,” other than some broad body of people consisting in equal measure of African-Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and others. But what, exactly, might such a coalition set about doing? What might its stated objectives? None of that is established.

The problem with such inquiries is that they boil down to matters of representation over policy. Policy is considered “wonky” and not something “average” people need to concern themselves with. As a result, prevailing conversations about electoral candidates on matters like race and inequality are too focused on whether or not their campaigns reflect enough diversity, making it impossible to have the harder and more necessary conversations about how their policies actually affect the disenfranchised.

When Black Lives Matter finally got its chance to interrogate and push Clinton on her past record, they failed miserably, asking her instead how it all made her feel and doing nothing to extract from her a sense of how and if she could be different. That allowed her to evade any real responsibility for the ongoing economic devastation wrought by her policies. Sanders does at least have statements on his website which take a more more nuanced view of the intersection of race and inequality but, again, these are being ignored.

Instead, we become obsessed and are even led away by internal factors in conversations which have nothing to do with the central questions at hand.

Consider, for instance, Sandra Bland’s horrific death in jail. For weeks, social media users became obsessed with whether she had hanged herself, had been killed by police, or whether or not photos of her mug shots were evidence that she was actually dead at the time they were taken. Suddenly, everyone was a mortician or a forensic expert. But what mattered at the end of the day was that a Black woman was pulled over by a white cop for smoking in her car—and that she was either killed or compelled to take her own life because of it. That itself speaks volumes to the effects of race and racism in the U.S.

But what, exactly, might such a coalition set about doing? What might its stated objectives? None of that is established.

Consider also the continuing questioning over whether police kill more black or white people. Neither scenario—one in white people are killed more often or another in which more black people are killed—should distract us from fact that there is, clearly, a problem with the gunning down of civilians by heavily armed police. Contrary to what some insist, there is a racial disparity, but it’s a complicated one: In terms of race, victims are roughly half white and half minority, but two-thirds of unarmed victims were Black or Hispanic, and Blacks are killed at three times the rate of whites or other minorities.

What we see, if we look closely enough at factors like, say, what neighborhoods these homicides tend to occur in, we would see more closely the relationship between racial, economic, and police violence.

But none of that makes for sexy chatter or the kinds of arguments that increasingly drive political conversations in the media. Instead, we’re left with meaningless and cliched questions about “multiracial coalitions,” even though—when it comes to America’s most pressing problems—that means absolutely nothing.

Yasmin Nair is a freelance writer, activist, academic, and commentator, the co-founder of the radical queer editorial collective Against Equality, and a member of the Chicago-based group Gender JUST. Follow her on Twitter.

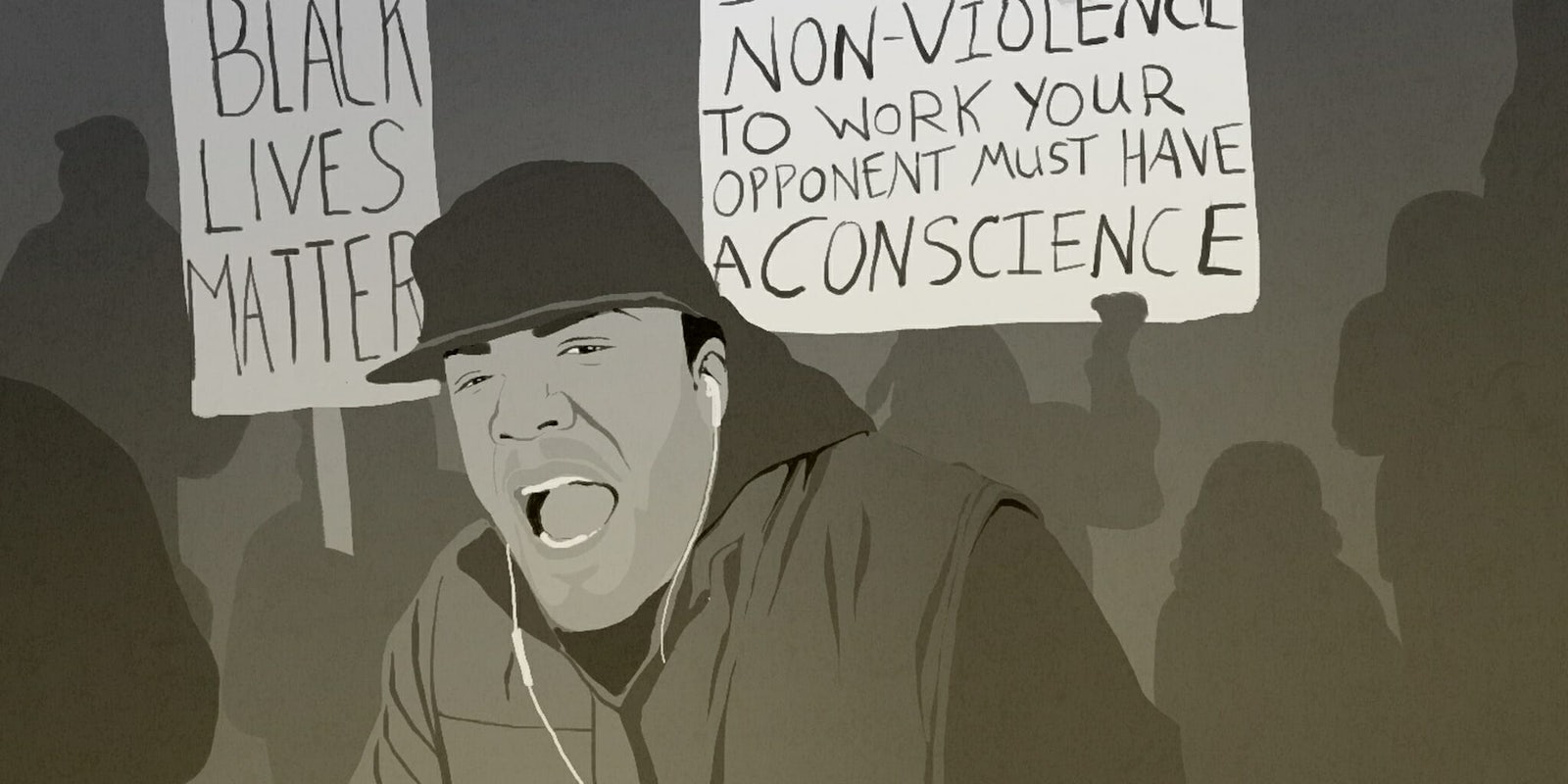

Illustration by Max Fleishman