BY JANE DOE

On Oct. 1, Vindu Goel wrote for the New York Times blog that Facebook was to “Ease Policies on Using Real Names for Accounts.” On Oct. 16, I woke up to find my Facebook account deleted.

I have had a Facebook since about 2007 or 2008. Other than when I was a kid and was afraid my parents would find out about my account (causing me to use an alias for a little while), my profile always bore my legal name. A week or so ago, however, I changed my display name to “Arc Angel.”

I did this because, in the past few months, due to my increased output in critical writing and stance on controversial issues, I have gotten a taste of what well-established advocates are known to receive: namely, abuse. There have been plans to troll and trolling efforts against my personal social media accounts and those of a survivor lit curation I co-run, Empath Lit; I have become the subject of smear campaigns; my likeness has been invoked in ways that I did not consent to; and I have received bullying messages, both from strangers and from past abusers. I realize that, with greater visibility, this will only be exacerbated, and changing my display name came with the hope that I could preemptively protect myself.

I did this, secondarily, because I am transgender, and, like many trans people, I am beginning to feel a disconnection from my birth name. I have been wrongly criticized—mostly by cisgender people—that I should expect misgendering because of my “female” name. I was content with my given name for a while, and I will likely continue to publish under it, but presenting myself by my legal name was aggravating my dysphoria.

I actually tried numerous times to change my Facebook name to a more androgynous and anonymous name that makes use of my legal name/initial and should be permissible under Facebook’s policy (as it accepts some informalities, like nicknames), but the minute change was continually rejected.

When Facebook’s chief product officer, Chris Cox, supposedly addressed the controversial policy over two weeks ago, he said:

Our policy has never been to require everyone on Facebook to use their legal name. The spirit of our policy is that everyone on Facebook uses the authentic name they use in real life. For Sister Roma, that’s Sister Roma. For Lil Miss Hot Mess, that’s Lil Miss Hot Mess. Part of what’s been so difficult about this conversation is that we support both of these individuals, and so many others affected by this, completely and utterly in how they use Facebook.

Accordingly, the language of Facebook’s name policy has changed from “legal” or “real” to “authentic.” If Facebook accepts naming as something so personal, why, then, have they—completely without warning, despite the fact that I have had no other “infractions” in my seven or so years of maintaining this account—disabled my profile and demand to be shown a government ID as the sole option for restoration? Why, if, as Cox writes in his post, Facebook values the “LGBT community,” have only the accounts of cisgender drag performers, using stage names (e.g. Sister Roma or Lil Miss Hot Mess, the only “LGBT” figures named in Cox’s post) been restored?

This is especially germane considering that, as Nadia Kayyali points out in “Privacy, Identity, and Facebook,” trans women (like Saudi Arabian user Leena, who is embroiled in her own ordeal with Facebook) “make up 72 percent of the victims of anti-LGBTQ homicide,” and yet none are acknowledged here.

And why, if Facebook is admittedly set on being a “powerful force for good,” does this company consistently fail the marginalized? The fact of the matter is, this “authentic” name policy—at least the mode by which it is enforced—serves to expose victims as readily as abusers. As Kayyali argued:

[W]hat’s really absurd about the policy is this: it isn’t even designed very well to do what it’s supposed to. Facebook’s enforcement team isn’t scouring the site looking for people who don’t comply with the policy… The only thing the policy really does is allow people to anonymously target others, by reporting them… [T]he real burden of the policy ends up falling on communities that have already been unfairly burdened, by discrimination, violence, and political repression.

Unsurprisingly, I know many people, both remotely and personally, for whom this situation is completely terrifying. This is precisely how innocent, and especially at-risk users—like trans people, sex workers, survivors, and activists—can be targeted, doxed, or silenced. This is precisely how a page advertising “Rapewave”—which, to my knowledge, has been reported as abusive many times over—can be left to stand, while my profile, part of a growing platform for survivor advocacy media, is deleted without warning. This is how an organization like Gender Identity Watch—one that spouts TERF politics, while seeking to dox trans women—is allowed, but trans women users have their accounts disabled for “inauthenticity.”

Virtually any survey of Facebook’s pages, groups, or user profiles begets something (most commonly racist or sexist content) that would qualify for deletion—and yet Facebook does not occupy itself, as Kayyali notes, with scouring what it hosts or checking in with suspicious users. For being so staunchly against “bullying, trolling, [threats of] violence, scams, hate speech, and more,” Cox et al. sure let a lot of things go.

As relayed in the Goel article, Cox has stated, in consideration of controversy, that the site is “already underway building better tools for authenticating the Sister Romas of the world.” Unfortunately for me, I am not a “Sister Roma,” and it seems my identity is not “Sister Roma”-like enough for Facebook’s standard of authenticity. This also does not bode well for the countless other marginal people who rely on social media for support and are not necessarily cisgender, or white, or successful.

Additionally, it is offensive to compare the names trans people use for themselves, or a protective pseudonym an at-risk person adopts, to something like an external stage persona or brand. Maybe if “Arc Angel” or “Angel Boy” had been my drag name, and not just the self-proclaimed crux of my expression of transness and reclamation of trauma, I would’ve gotten off with a warning.

Sister Roma herself—the performer whose likeness Facebook seems to equate with inclusivity—actually disagrees with the company’s myopic response as well and has worked extensively to secure the rights of all affected Facebook users, beyond the drag community. When reached for comment, she wrote the following to me in an email:

While I appreciate Facebook’s acknowledgement that their policy has allowed the drag community to be unfairly targeted, I do feel like they are failing to address the much larger global impact of this unfair policy. My fellow #MyNameIs protestors and I have always emphasized the dangerous implications of the current policy to many facets of Facebook society, including trans men and women, political activists, survivors of domestic violence, [and] bullied youth; the list goes on and on.

There are a million people who use chosen and protective names on Facebook for a million valid reasons. On Columbus Day, a group of Native Americans were reported and their accounts were suspended. Enforcing this policy as it now stands will only continue to blow up in their face. Facebook assures us that they are working on developing backend software that will classify accounts as being authentic (i.e. not fake accounts set up for trolling, spamming, or grooming, among other things) that will greatly reduce the incidence of false reporting.

Meanwhile, we are working to restore accounts on a one-on-one basis and keeping pressure on Facebook to deliver on their promises. Unfortunately, this takes time, and as profiles continue to be targeted and suspended, it’s becoming quite clear that time is running out.

Whatever amendment Facebook has made to their policy smacks of soft exploitation—that is, catering redress to the most vocal and visible of minorities, whether they seek favoritism or not, and accommodating conflicts only when they become too obvious to ignore. This is what guides Facebook to offer any number of options for “gender” on a profile, branding themselves as inclusive, while simultaneously rejecting the “authenticity” of individual trans or otherwise marginal identities.

Facebook not only has rejected the submission of my government-issued state ID once already and ignored the extenuating context I supplied to them, stating that the information was inadequate, locking me out of my account (though I will appeal this process until I am barred), but they also, when I attempted to start over with an alternative profile, disabled it within the day. To reiterate: despite the fact that I have complied with their abrupt and imposing requirements, Facebook continues to deny me the rights to privacy and identity that they openly afford to users of more visible and normative demographics.

Are we not all entitled to our “authenticities?” Evidently, despite Chris Cox’s optimism, Facebook doesn’t agree.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to enhance the privacy of the author.

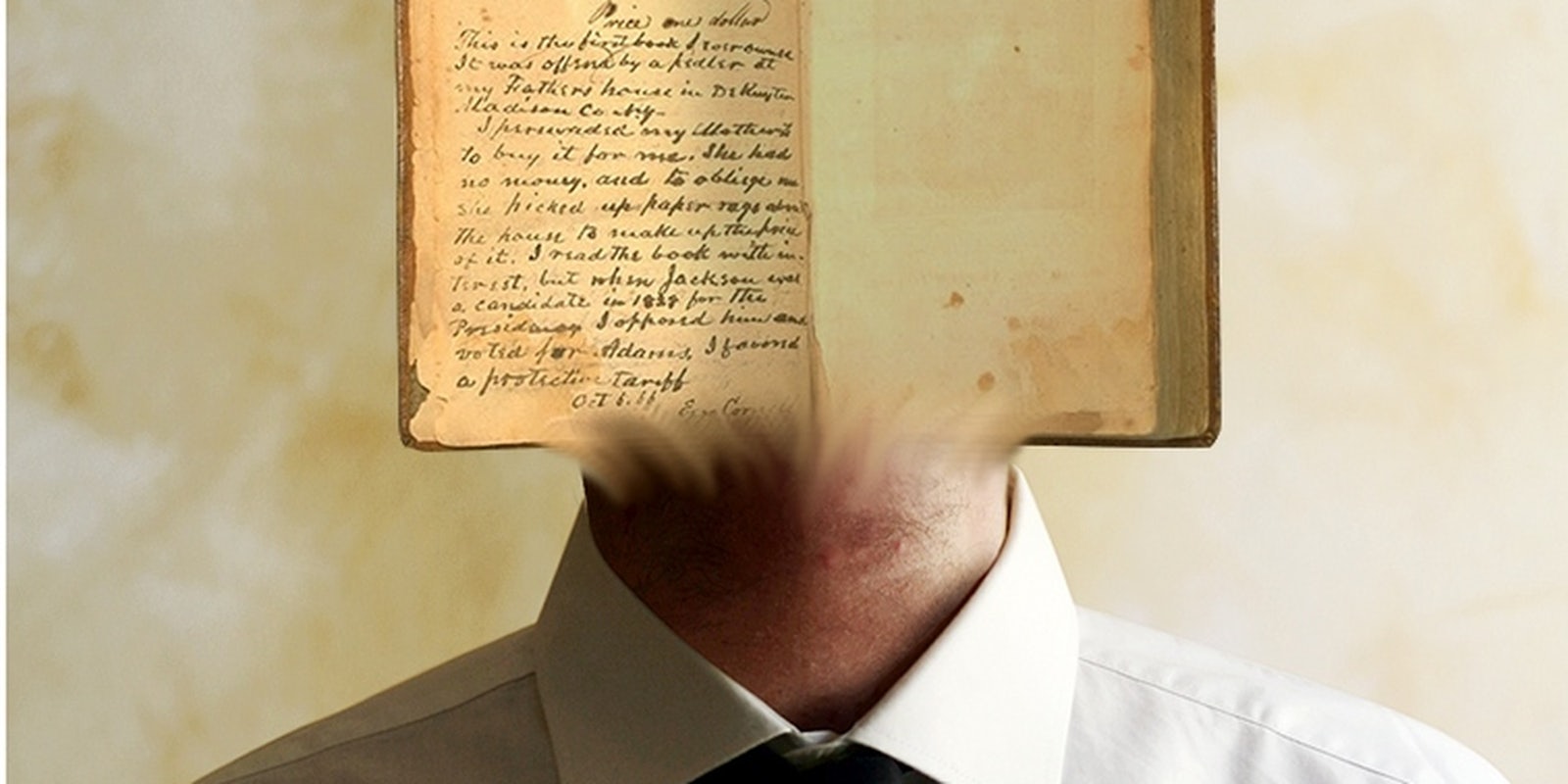

Photo via _Max-B/Flickr (CC BY S.A.-2.0)