In its prime, the ancient neighborhood of Petsburg may have had as many as 10,000 homes. And though they are now abandoned, traces of their inhabitants still hide in the ruins. “I just LOVE attention!,” a resident named Gypsy once wrote in her long-forgotten journal. Another resident named Cosmo confessed, “I don’t mean to be a bad cat, but being good is very difficult.” Names of these neighbors linger on the walls and in guestbooks. There was Fuzzy, Tinker, Nipper, Spice, Boomer, Lady Sustina, Whisky, and countless others too, now scattered, if they’re still anywhere at all.

Petsburg appears to have enjoyed a bustling commercial district during its heyday. There were shops where one could do everything from having their age in dog years calculated to adopting one of the community’s abandoned pets. The neighborhood library recorded the histories of ancient creatures, like, for instance, the Egyptian Mau (“To gaze upon this beautiful and engaging [cat] is an opportunity to view a living relic,” one historian wrote.) Meanwhile, its scientists painstakingly chronicled the stages of gerbil pregnancies (“12/23/98: Moonflash and Chequers could double as gourds! they are both expecting any time now,” a researcher observed.) Visitors traveled the neighborhood on Webrings, leaving their mark in each home’s guestbook. The local newspaper was the Petsburg Post, though no copy has survived the community’s complete collapse.

Petsburg was just one of the 40 neighborhoods that made up the metropolis of Geocities, which, in its 15 years of existence, housed some 38 million online residents. It was arguably the world’s first and last Internet city. Were it a physical place, it would have been by far the largest urban area in the world.

It was shuttered in 2009, but several archive groups and individuals have sought to preserve it on mirror sites like Reocites and Oocities, and in massive torrent files. A relic from the early days of the Internet, frozen and downloadable, the files tell the story of the city’s rise and downfall, the story of how we found our place online.

Geocities homepage for Egyptian Mau in Petsburg neighborhood. Screengrab via Reocities

Geocities began in 1994, advertising an enticing 15 megabytes of free space to any homesteader looking to make their place on the Web. The World Wide Web was only a few years old when this digital Northwest Ordinance was issued, and so its users, often referred to as netizens, were necessarily having their first interactions with the Internet, learning to make a place for themselves in the newly discovered online world. Millions of netizens with little to no experience or understanding of how a webpage “should” look utilized the site’s built-in development tools to create clapboard homes spattered with stray GIFs, looping MIDI files, and busy backgrounds. It was the Internet’s Wild West.

Geocities homepage of “Davelicious Dave Feinman” in Sunset Strip neighborhood. Screengrab via Reocities

It is easy to dismiss these pages as a sort of outsider art. But outside of what? There was no such thing as a personal page before Geocities. And, in almost every meaningful sense of that word, there is no equivalent today. Consider a page from the Heartland neighborhood, where one resident wrote, “Hi! My name is Sherry, my husband is Richard. We have three children, Colleen, Alicia and James and we are out here in the desert of southern California.” Further down on the page is a link to “Richard’s Original Bedtime Stories”: “Once upon a time there was a mad scientist, and this mad scientist had a laboratory. In his lab the scientist had a shelf and on the shelf was a jar. In that jar was a pickle and in the pickle was DNA. This DNA was different, it was dinosaur DNA…”

Where today do families publish their homemade bedtime stories about giant pickles? Sites like these have simply disappeared.

Where today do families publish their homemade bedtime stories about giant pickles? Sites like these have simply disappeared.

Geocities was bought by Yahoo in 1999, during the height of its popularity. Then along came Myspace in 2003, Facebook in 2004, and Twitter in 2006. And by 2009, Petsburg, Heartland, and the rest of Geocities had been shuttered. The world had chosen the pre-fab aesthetics of social networks over the 15-megabyte tracts of open land offered by Geocities. Jacques Mattheij, the founder of the Geocities archive site Reocities, explained this choice to me: “The Geocities environment offered more freedom for expression. Don’t like blue? Then Facebook probably isn’t for you.”

Whatever we may ultimately make of our move towards sites like Facebook, it’s almost certainly the case that, for the average netizen, it was a movement away from online literacy. Instead of slogging through the HTML editor of Geocities—and coming to terms with how these tools can be used to express oneself in a digital space—we chose the sleek, standardized layouts of Facebook and Myspace.

“There’s no way to look at the Facebook page and not know that you’re on Facebook,” Jason Scott, who worked on a Geocities preservation project with Archive Team, told me. “In fact, it’s hard to be on Facebook and even feel like people are contributing much beyond links and a paragraph of text.”

Online and before, we’ve always made these choices. The American west is littered with forgotten towns, single-economy communities that cropped up to mine gold, build railroads, or raise livestock as the country made its stubborn progress to the Pacific. Those that survived eventually lost their pioneer character.

Perhaps there is no better example than the city of San Francisco, once a wooden outpost at the edge of the world for gamblers, fishermen, and miners—and now, with Silicon Valley, arguably one of the most modern places in the world. In the language of online communities, it was a Geocities that became a Facebook. Whether these concessions we make in the face of technological progress are a good thing is difficult to say. Gold Rush-era San Francisco was a brutal, crime-ridden place where riches went as quickly as they came from the city’s mostly drunk, mostly male population. Still, when any city disappears, something is lost.

The ghost town of Bodie, Calif., once a mining community in the Sierra Nevada mountains. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith/Library of Congress

Unlike Facebook, where relationships are for the most part determined by previously established acquaintances or friendships, the organization of Geocities, and thus life online at the time, was based on the idea that one occupied a specific spot in the Internet world—quite literally, a homepage. A person moved into a particular neighborhood—be it Petsburg, Heartland, Area 51, Hollywood, or any other—and then met strangers with common interests. The residents of Petsburg, for example, knew each other not because they had met in real life first, but because they were situated in the same digital community. They read the same Petsburg Post and signed the same guestbooks. For better or worse, they were neighbors.

In a community—online or in the world—a “friend” and a “neighbor” are two very different things. In Jane Jacobs’ influential study, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, she contemplated how urban planners attempting to redesign cities with attractions like enclosed spaces and major highways have failed to understand the notion of a neighbor. In one particularly telling passage, she developed the concept of a neighbor by explaining why everyone on her block leaves their key with a man named Joe who works at the corner store. “Now why do I, and many others, select Joe as a logical custodian for keys?” she began. “[Because] we know that he combines a feeling of goodwill with a feeling of no personal responsibility about our private affairs. Joe considers it no concern of his whom we choose to permit in our places and why.” For Jacobs, battling urban planners in 1950s New York, the problem in this case is that developers attempt to institutionalize these sorts of informal, neighborly relationships. But, as she put it, “a service like this cannot be formalized.”

In the online world, Facebook regularly attempts just such formalizations. Consider the concept of “friending” another person. It gives users access to each other’s social networks, photos, educational history, and countless other perfectly organized bits of information and interests that could otherwise require years of interaction to discover. That is, on Facebook, there is only one type of relationship: friend. Because of this, one doesn’t (generally) friend people they haven’t met. And so communities on Facebook tend to reflect and preserve relationships out in the world. Who would meet a total stranger online and give that person instant access to the entirety of their private digital life? A decade of users on Facebook provide the answer: not many. As Jacobs argues, this flattening of the nuances of human relationships cannot produce a meaningful community. This has happened across most, if not all, social media platforms. And as a result, communities like Petsburg disappeared.

The loss is considerable. Even if you take exception to the argument that the streamlining and commoditizing of relationships is incompatible with the notion of community online, one fundamental difference between Facebook and Geocities still remains. As Jacobs wrote, “assume (as is often the case) that city neighbors have nothing more fundamental in common with each other than that they share a fragment of geography”—in the Geocities world, we might call that an interest or topic, like pets or blues music. “[If] they fail at managing that fragment decently, the fragment will fail. There exists no inconceivable energetic and all-wise ‘They’ to take over and substitute for localized self management.”

In other words, as soon as all the members of Petsburg no longer take an interest in each other, or in each other’s pets, the community will cease to thrive, and soon it will die. Facebook is quite a different story. If you stop using Facebook, the company will start sending you emails, telling you that your friends are doing something interesting, prompting you to participate in the community again. The company insists that “communities” form and thrive, regardless of whether they are naturally inclined to do so. Facebook, in essence, is the “They” Jacobs is referring to, and which she calls “silly and destructive.” By “destructive,” Jacobs means artificial, planned, fake, insincere. Or in the parlance of city planning: suburban.

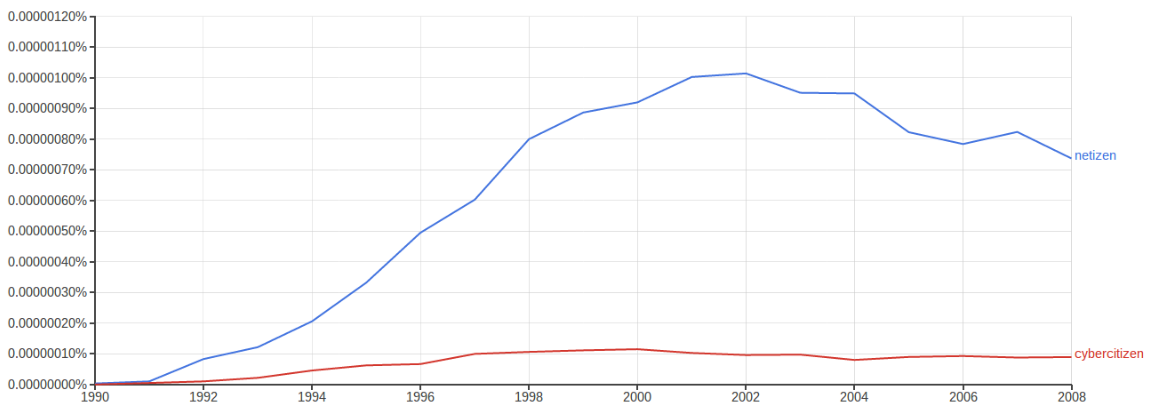

One way to make sense of the change in the way we live online is to consider how the language we use to talk about our digital selves has evolved. Take terms like cybercitizen and netizen, which each play on the metaphor that the Internet is a structured city or community. According to Google Ngrams, these words found their greatest use in the heydey of Geocities and have been in decline ever since. This happened as we began clicking friend buttons instead of writing in the guestbooks of neighborly strangers. It happened as we traded in our HTML editors for the sleek blue layouts and pre-set photo sizes of Facebook. In other words, we stopped being frontiersmen and started being consumers, conceding the role of maker in our Wild West to corporations. And build they did.

In short, we gave up our netizenship.

“The sense that you were given some space on the Internet, and allowed to do anything you wanted to in that space, it’s completely gone from these new social sites,” said Scott. “Like prisoners, or livestock, or anybody locked in institution, I am sure the residents of these new places don’t even notice the walls anymore.”

The usage of the words “netizen” and “cybercitizen” since 1990. Graph generated with Google Ngram Viewer.

What the decline of the netizen really shows, of course, is not simply that Geocities is gone, but that the entire notion of a Web community has changed. The Internet we have created is no longer in the image of the city.

In many ways, real-world cities themselves have abandoned the idea of neighborhood communities. One might reasonably ask, for example, how many new people one meets each day anymore in a place like San Francisco, the technological mecca of the world, when everyone is constantly connected to friends through their smartphones. Concede that we want these new devices ,and we must also concede that we don’t value the happenstance meeting of strangers or obligations to neighbors at the corner store as much as we once did.

In many ways, real-world cities themselves have abandoned the idea of neighborhood communities. One might reasonably ask, for example, how many new people one meets each day anymore in a place like San Francisco, the technological mecca of the world, when everyone is constantly connected to friends through their smartphones. Concede that we want these new devices ,and we must also concede that we don’t value the happenstance meeting of strangers or obligations to neighbors at the corner store as much as we once did.

In short, we didn’t simply abandon the notion of city-like communities on the Web; we abandoned the notion of city-like communities.

“There’s a period in technology where technology needs to emulate things that came before it for people to understand their place in it,” Scott said. “Sometimes this could be entertaining indeed, but it does ultimately limit what the new medium can do.”

In this sense, the archives of Geocities become not just ruins of the early Internet, but an artifact of the way we used to enjoy living among one another. Perhaps there are no more family pages telling strangers about giant pickle bedtime stories because families have stopped longing to share those things with a community of strangers. Petsburg, Heartland, and the other neighborhoods of Geocities all sprung from our notions of community before smartphones, tablets, Wi-Fi, and blogging. They reflect a bygone time before the daily newspaper migrated online, when citizens once made their daily, early-morning trek to the corner store, gathered with neighbors, shared a cup of coffee, dropped off their keys, and grumbled about the terrible weather they had to step out into just to get the morning’s headlines.

The question is, are we happy with this trade?

Illustration by Jason Reed