The concept behind gamification is relatively simple. Just take techniques developed in the world of video games and apply them to the world of education—from points and leaderboards to killing monsters and saving princesses.

At this year’s South By Southwest conference, there are no less than 20 panels that deal with gamification or game-based learning by name, with panels like “Games in the Classroom,” “Gaming Theory: The New Look of Math Class,” and “Minecraft Your Classroom.”

‟A common theme among all the different branches of SXSW is ‛engagement,’” explained Greg Rosenbaum, one of the producers of the portion of the festival specifically focused on education. “Engagement with music, with technology, with the environment. So focusing on games, which by their very nature engage necessarily engage with players, seemed like a natural fit.”

The growth in both size and maturity of the educational games industry extends well beyond the sprawl of SXSW, though. Educational gaming is expected to swell to over $2.3 billion in revenue by 2017.

However, as game producers see dollar signs and educators see a way to finally get fourth graders legitimately excited to learn their multiplication tables, there’s a growing legion of skeptics who fear this rush to transform education into a video arcade may be nothing more than a distraction.

From Pong to algebra

In 1969, Nolan Bushnell founded a company called Syzygy, which created the world’s first arcade computer game. Three years later, realizing that the name Syzygy was already being used by a hippie candle company, Bushnell changed it to Atari. Atari went on to create Pong, the first successful, mass-market video game in history, as well as launch the first generation of home video game systems. When America was first introduced to video games, Bushnell is widely considered to be the man responsible.

So when Bushnell, who is appearing on a SXSW panel on the subject, says he’s been thinking about the educational power of video games from the very beginning, he’s literally talking about the first moments anyone was thinking about video games.

So when Bushnell, who is appearing on a SXSW panel on the subject, says he’s been thinking about the educational power of video games from the very beginning, he’s literally talking about the first moments anyone was thinking about video games.

“I immediately found that video games are satisfying to kids; you can even call them addicting, because they represent a very tight, sensitive and thrilling environment,” Bushnell explained. ‟[I realized] everything that we’ve thought about traditional school subjects can be set to games.”

When Bushnell left Atari in the late 1970s, one of the first things he did was create TimberTech Computer Camp. Nestled in the woods just south of Silicon Valley, TimberTech was a place where kids used computers as learning tools on a daily basis.

A serial entrepreneur who has founded nearly two dozen companies over the course of his lifetime, Bushnell quickly got distracted by other pursuits. (He founded Chuck E. Cheese for starters.) However, about five years ago, he came back to to educational gaming with a company he founded BrainRush. True to form, he said it was only last year when he really got deep into it.

Brainrush

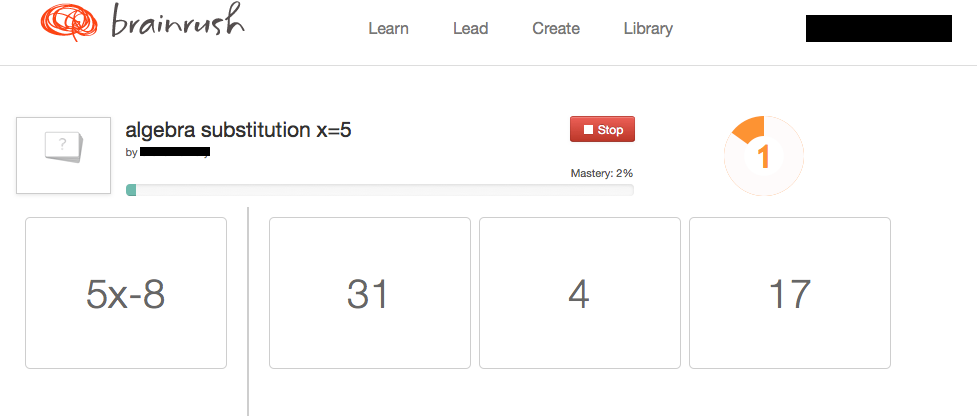

BrainRush is what Bushnell calls ‟an adaptive learning platform” that can be applied to a virtually any subject through a set of game-like templates. In practice, BrainRush plays like a series of timed flash cards that earn their users ‟genius points” for successful completion of each round. Bushnell notes that some 1,300 educators have uploaded lessons to the BrainRush platform—at a rate of between 50 and 100 per day—on subjects ranging from basic Spanish to music theory. He calls it “a mixture of Zynga and Wikipedia.”

BrainRush uses a bevy of techniques derived to research into the psychology of how people learn, such as requiring players to input some kind of response every three to five seconds and questions that change in difficulty based on how players are doing. Bushnell boasts that teaching something using the BrainRush platform can lead to a tenfold boost in the retention rate of information over pen-and-paper flashcards.

What Bushnell is doing with BrainRush is the core of gamification. It’s the direct application of elements of video games to traditional educational practices. It has all the hallmarks of what Gabe Turow, a doctoral candidate at Columbia Teacher’s College focusing on educational gaming, points to as being necessary for an education game. Turner believes educational games need to give players immediate feedback on how they’re doing at all times, with rewards (such as points or badges) to encourage forward progress, and to make failure acceptable by giving players infinite lives without significant punishments for wrong answers.

What Bushnell is doing with BrainRush is the core of gamification. It’s the direct application of elements of video games to traditional educational practices. It has all the hallmarks of what Gabe Turow, a doctoral candidate at Columbia Teacher’s College focusing on educational gaming, points to as being necessary for an education game. Turner believes educational games need to give players immediate feedback on how they’re doing at all times, with rewards (such as points or badges) to encourage forward progress, and to make failure acceptable by giving players infinite lives without significant punishments for wrong answers.

Even so, what Bushnell is doing with BrainRush is only one side of the educational gaming coin. On the other, is someone like Gary Goldberger, the CEO of a company called FableVision that takes a very different approach.

One of FabeVision’s most notable recent efforts is a game called Lure of the Labyrinth. Created in conjunction with MIT’s Education Arcade and the Maryland Department of Education, the concept behind Lure of the Labyrinth was to create a game that could replace a middle school math textbook. In the game, players have to delve into a foreboding dungeon and save their kidnapped pet by solving math puzzles that have been carefully crafted to fall into alignment with Common Core standards. The game, which is freely available online, has been played by more than a quarter-million middle school students.

Lure of the Labyrinth

“Lure of the Labyrinth is less about drilling content into kids heads as it is about creating an engaging experience teaching the underlying fundamentals of mathematics,” Goldberger insisted. “The game mechanics and the core dynamic of game should be the thing that teaches math rather than just giving out points and badges for doing torturous drill-and-kill repetition.”

What in the world happened to Carmen Sandiego?

To anyone who came of age in the 1990s, the concept of educational gaming isn’t anything particularly novel. ‟Edutainment” games like Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego and The Oregon Trail were ubiquitous on home PCs and in school computer labs. But, by the end of the decade, the industry had imploded. To put it in terms anyone who spent hours playing Oregon Trail can understand: Edutainment lost all of its oxen in an attempt to ford a river and then died of dysentery.

GIF via Imgur

A 2012 report on the subject from Sesame Workshop’s Joan Ganz Cooney Center explains how this failure still reverberates. ‟Today, publishers tend to stay away from the word ‛educational’ in the consumer video game space. In fact, one would be hard pressed to find a recent mainstream success story of a big budget video game in the consumer space that was designed, developed, and marketed as educational,” the report reads.

Recent popular games like Little Big Planet, The Sims, and Minecraft all have substantial educational value, but none of them exist in an explicitly educational sphere.

In telling the story of the fall of edutainment, the report points the finger at industry consolidation. Over the course of the decade, a firm called the Learning Company gobbled up a litany of its competitors and become so successful that, at one point in the late 1990s, it had the second-highest revenues of any consumer software company in the world—behind only Microsoft. Sensing a golden opportunity, Mattel bought the Learning Company for $3.8 billion in 1999.

The deal was a disaster—mainly because it coincided with a fundamental change in the way educational software made its way to customers. Initially, most software for kids was sold through speciality stores like Babbage’s and Software Etc. However, with the rise of big box stores like Walmart, the primary distribution channel shifted. Smaller gaming companies found it nearly impossible to get their games in stores. Bigger players, like the company subsequently branded as Mattel Interactive, were ‟forced to slow innovation in an effort to keep prices down and maintain shelf space. … Although product was moving, publishers weren’t able to make enough money at these lower price points to invest in innovation, either in content or in format.”

Games that were initially retailing for $40 were suddenly marked down to $10 and quality declined precipitously. Consumers were trained to think of educational games as cheap, second-rate products and sales tanked. To this day, Mattel’s purchase of the Learning Company is considered by some to be one of the most ill-advised acquisitions in modern business history.

The moral of this story is that securing sustainable distribution channels is essential for the comeback of educational games to make sense economically. In this respect, the people producing educational games face a stiff headwind.

One of the biggest trends in gaming right now is toward simple, casual games that can be played on mobile devices. On one hand, that’s a great thing for educational game makers because it means every kid walking around with a smartphone in his or her pocket now has an easy-to-use portal to learning math. “You can’t get a kid off of an iPad.” said Goldberger, ‟We can use that to educate.”

One of the biggest trends in gaming right now is toward simple, casual games that can be played on mobile devices. On one hand, that’s a great thing for educational game makers because it means every kid walking around with a smartphone in his or her pocket now has an easy-to-use portal to learning math. “You can’t get a kid off of an iPad.” said Goldberger, ‟We can use that to educate.”

At the same time, this distribution mechanism presents the danger of once again falling into the quality trap. Since getting a game into the app store is far easier than getting it into a Walmart, the barriers to entry are low. The economics of the ecosystem tend to reward developers who can make games that are fast, cheap and briefly very addicting before users inevitably move on to the next trifle. This system works great for games where the only goal is to guide a frustratingly difficult-to-control bird through an endless series of pipes. When crafting a game designed to teach young learners how to solve algebra equations effectively—something that likely requires a significant amount of pedagogical research—treating the development of educational games the same way as ones designed solely for entertainment suddenly becomes fairly problematic.

The economics behind creating games to be used in school classrooms may be even more challenging.

‟The problem with getting a piece of software used in school is that adoption is slow,” Goldberger explained. ‟There’s bureaucracy; there’s convincing teachers that this program is something good for their classroom. You have to wait around for at least five years to make your money back [on an educational classroom game].”

Larger software publishers can get around this by subsidizing a product’s short-term loses on the assumption that a game will make its money back when adoption occurs further down the road. Small developers, on the other hand, don’t have that option—effectively closing the little guys out of the process.

One option would be to urge school districts around the country to make it easier for teachers to adopt new games in their classrooms. Jordan Shapiro, a psychology professor at Temple University who has written extensively about educational games, argues this would be a mistake.

‟There are a lot of games in the app store that are really invasive when it comes to privacy; a lot of them don’t belong in schools for precisely that reason,” he insisted. “The last thing we need is to remove the slow-moving vetting process. Debates about educational quality should be slow-moving.”

Instead, Shapiro asserts, government intervention is necessary. ‟There’s no system right now that allows tiny developers to get games into the classroom because of high startup costs and long window for investment recovery,” he said. ‟We need to have government investment into this independent educational game pipeline.”

Leveling up or dumbing down?

Despite the roadblocks, there’s more energy behind the idea that video games are an invaluable learning tool than ever before. The reason for this shift is largely generational. The people who grew up with Mario Kart learned everything they know about geography from chasing Carmen Sandiego are now becoming teachers, school administrators, and game developers themselves. Much of the stigma once associated with gaming has since fallen by the wayside.

This widespread, intimate, lifelong familiarly with the way video games work isn’t just having effects on education. Gamification is having a major effect on a whole host of different fields from retail to human resources.

“One reason for the prevalence of gamified educational experiences is that gamification is so hot right now that its easy to get capital to back projects that have the word ‘gamified’ in their pitch,” Shapiro explained.

However, gamification does have its skeptics.

Dr. E. Michelle Ramsey, a professor of communications at Penn State, worries that gamification has the potential to give students the wrong message about the hard, often grueling, work required to gain an education.

‟When we define learning as best served by active engagement and then summarily exclude anything that doesn’t engage students in playing ‘games’ linked to course content, we teach our future leaders that education can only be useful/worth their time if it’s entertaining,” she said.

‟What happens when students who have been inundated with ‛education that’s always fun’ have to deal with college courses where, in many cases, faculty haven’t bought into the gamification of education?” Ramsey continued. ‟Perhaps even more importantly, what happens when they enter the work world? Are their bosses going to work hard to ensure that work is ‛fun’? That meetings are ‛fun’?”

Even some advocates of the power of educational games have concerns about the potential negative consequences of simply adding game mechanics to everything. “I think gamification is misguided. It’s an exercise in political spinning to keep education exactly the same,” Shapiro said. ‟I don’t see in what fantasy world badges are any different than grades. I don’t see how leveling-up is any different than moving from one grade level to the next.”

‟Kids don’t play games to level-up, they do it explore the game’s world,” he added. “Does anyone actually care about getting a high score in Mario Brothers? No. The only real reward is beating the game.”

Instead, Shapiro said that the focus should be about embedding the subject developers are trying to teach into the very fabric of the game itself—something that the best game makers today are doing exceptionally well. He pointed to Dragon Box, a game that boasts “it secretly teaches algebra to your children,” as a great example.

‟At the end of the day, [a game’s educational potential] is only as good as the game itself,” Turow concurred. “These are pieces of art that are just as complicated as music or movies or paintings—probably more so. If you just drop game mechanics onto something without really thinking about it, you’re going to bring in all of the bad parts of video games without also bringing in their added benefit.”

Photo by Corey Leopold/Flickr | Remix by Jason Reed (CC BY-SA 2.0)