A cache of unknown stories by Mark Twain has been unearthed, but not in a mouldering crate in an attic or a tin box in an old barn and not overnight—but after years of searching. This cache was found and brought together in large part by sifting through the now-ubiquitous digital archives of Western newspapers.

Advancing on the work of scholars that came before them, Bob Hirst, editor of University of California, Berkeley’s Mark Twain Papers and Project, and his team, have found stories and articles that Twain wrote in the mid-1860s, ostensibly as a journalist for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise. From October 1865 until March 1866, Twain was paid to churn out 2,000 words a day, five or six days a week, from San Francisco for $100 per month.

Much of his output was lost in several fires at the Territorial Enterprise and some was reconstructed by searching the paper archives of other regional papers that carried the pieces, as well as several scholarly publications and a Twain scrapbook. But by searching the now common digital archives of regional newspapers and academic and cultural institutions, Hirst and his crew found a host of additional articles, driving the number of San Francisco stories by Twain up to 117 pieces, many complete but some excerpts and fragments.

According to Richard Bucci, the editor of the upcoming University of California Press-revised scholarly edition of the Territorial Enterprise letters, Mark Twain’s Writings: San Francisco 1865-1866, the new book will contain about 65,000 words of the correspondence. Despite doubling the number of Territorial Enterprise letters, Bucci told the Daily Dot he estimates that the collection is still only about 25 percent of the original total. So there is a lot of Twain writing out there still to find, if it is not irretrievably destroyed.

Of the 117 pieces, Bucci said 20 percent of the work was revealed via online searches. But at least as interesting to Bucci as the pieces found online was where they were found.

“What was exciting was how his writing carried around the world. You have to realize, he was a young writer. He didn’t have a book out. But his writing spread across the English-speaking world, with newspapers in the U.K., Australia, and Canada reprinting these works.”

Under the leadership of Hirst, the group, led by Bucci, poured over Brewster Kale’s Internet Archive, Google Books, Google, and Google News, and a host of full-text newspaper databases, the Library of Congress’s “Chronicling America” site, and the California Digital Newspaper Collection to find new copies of the stories.

The articles found are undeniably Twain. His friend and editor of the Territorial Enterprise, Joseph Goodman, called the stories, “among the best things he ever did.” They include one in which Martin Burke, then police chief of San Francisco, was likened to a dog chasing its tail to impress his mistress, and for which he was subsequently unsuccessfully sued by the chief’s chums. He explained that the dog had a mistress, not the chief.

“Chief Burke don’t keep a mistress,” he clarified. “On second thoughts, I only wish he did… Even if he kept a mistress, I would hardly parade it in the public prints. Nor would I object to his performing any gymnastic miracle… to afford her wholesome amusement.”

On the SFPD as a whole he said, “Wax figures, besides being far more economical, would be about as useful. Punishment of lawbreakers is, in some favored cases, almost obsolete.”

Another is a dialogue between two prospectors stranded down a shaft in Tuolumne County, and clinging to a rope, after having fallen when their line snapped, then caught, and their useless horse, Cotton, ambled off in “profound meditation.” One miner comments to the other, “Johnny, I’ve not lived as I ought to have lived. Damn that infernal horse! But Johnny, if we are saved I mean to be a good man and a Christian.”

The, shall we say, surprising detail of the miners’ conversation (a level of fingerprint detail any journalist can attest is a bit difficult to get at the best of times) provides a bridge between Twain’s straight reportage and his imagination and presages the use of that harmony and tension in future novels like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.

At the time these stories were written Twain was fighting tooth and nail against his natural inclination toward humor. Everyone knew comedy was for those whose spirit is too decadent for a nice epic or tragedy. Right? The ladies know what I’m talking about.

However, comedy and satire can have a pointed end, and Twain used that point to poke at those responsible for brutality against the city’s Chinese population and the graft of the police department.

However, this was the time period in which Twain wrote some of the most recognizable stories of his career, stories that established him as a diabolical observer of both the worst and the best in the human animal, stories like The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County and inspired his novel Roughing It.

He was also in debt and hitting the sauce with desperate enthusiasm. His distress was such that he wrote his brother during this time that he was considering suicide.

It was also the time when he met fellow writers, like Bret Harte, and America’s first standup comic, Artemus Ward, who connected Twain to the first American bohemians, who met in the Manhattan basement saloon of Charles Pfaff’. This group included the poet Walt Whitman America’s premier drug adventurer, Fitz Hugh Ludlow, and Henry Clapp Jr., whose publication, the Saturday Press, gave Twain entre to East Coast literary society a continent away.

“These letters give us a new look at the kind of talent that he had,” Hirst told the Daily Dot. “It’s much more obvious how talented he is than if you pick up, for instance, Huckleberry Finn. You take a lot for granted, as a result of its being around for so long and not being taught very well in school. But the letters give us a very fresh and exciting look at the kind of talent he had: highly verbal, very smart, and funny.”

Looking at Twain’s first paid writing gig also gives us a sense of how integral facts were to his fiction and fiction to his facts.

“One of the core truths of Mark Twain is he liked to get ahold of true stories and tell them in his own way,” said Hirst. “The truth is a starting point for Twain. He’s sui generis.” His writing is not the result of literary predecessors, Hirst said, but of experience at a hinge of history. “His career replicates the experience of America.”

Eventually, Twain took his gun out of his mouth and himself out of the Bay Area, and headed to Hawaii, a good alternative to both San Francisco and suicide. If there’s a difference between the two.

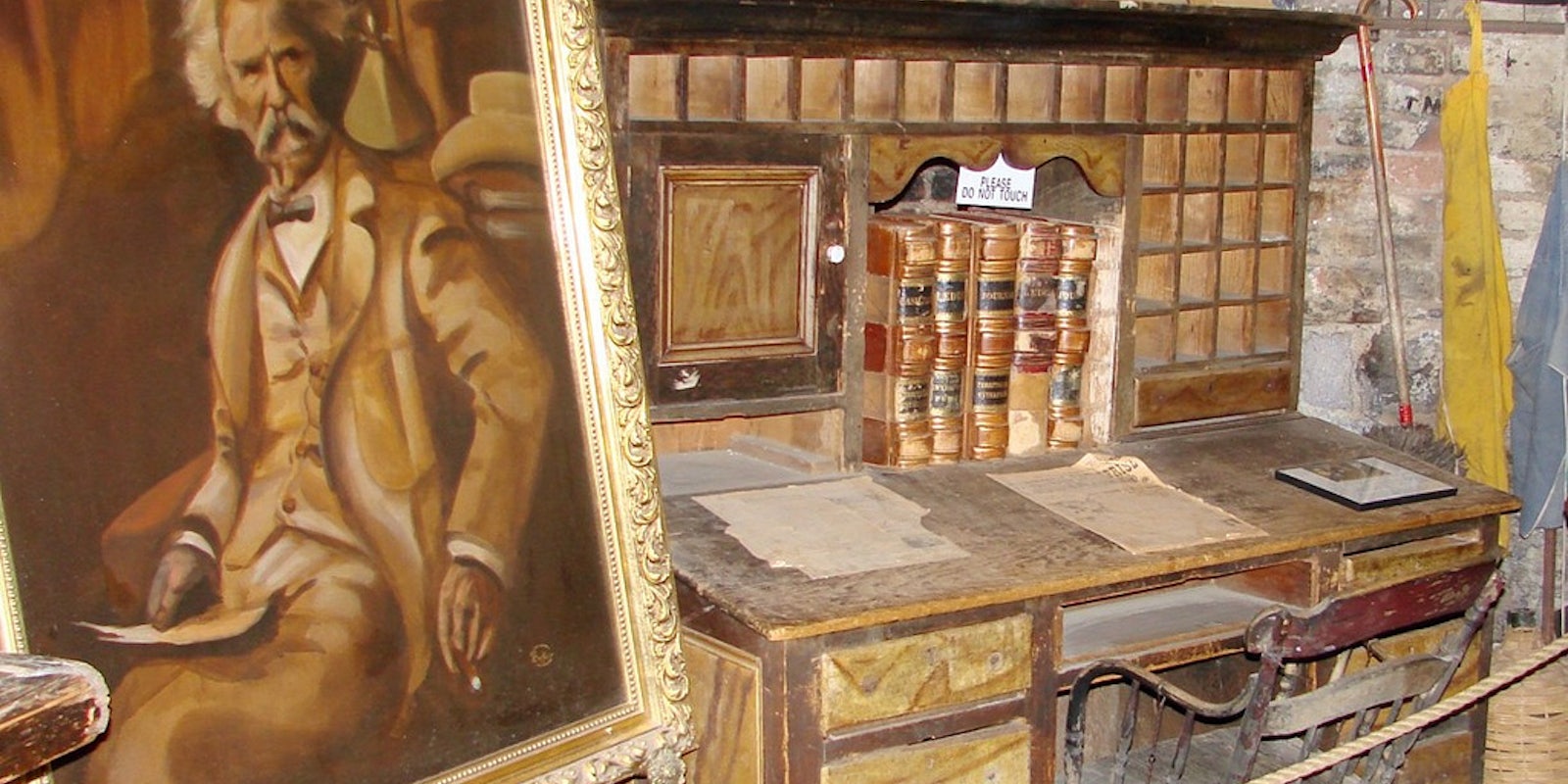

Photo via Don Graham/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)