BY BARTEES COX

Editor’s note: On Thursday, the House Judiciary Committee will discuss Section 512 of the Digital Millenium Copyright Act (DMCA), 1998, the law that dictates how the U.S. treats copyright on the Internet. Section 512 is likey the DMCA’s most controversial, as it dictates how copyright owners can get their material removed from other people’s sites, though critics argue this leads to abuse.

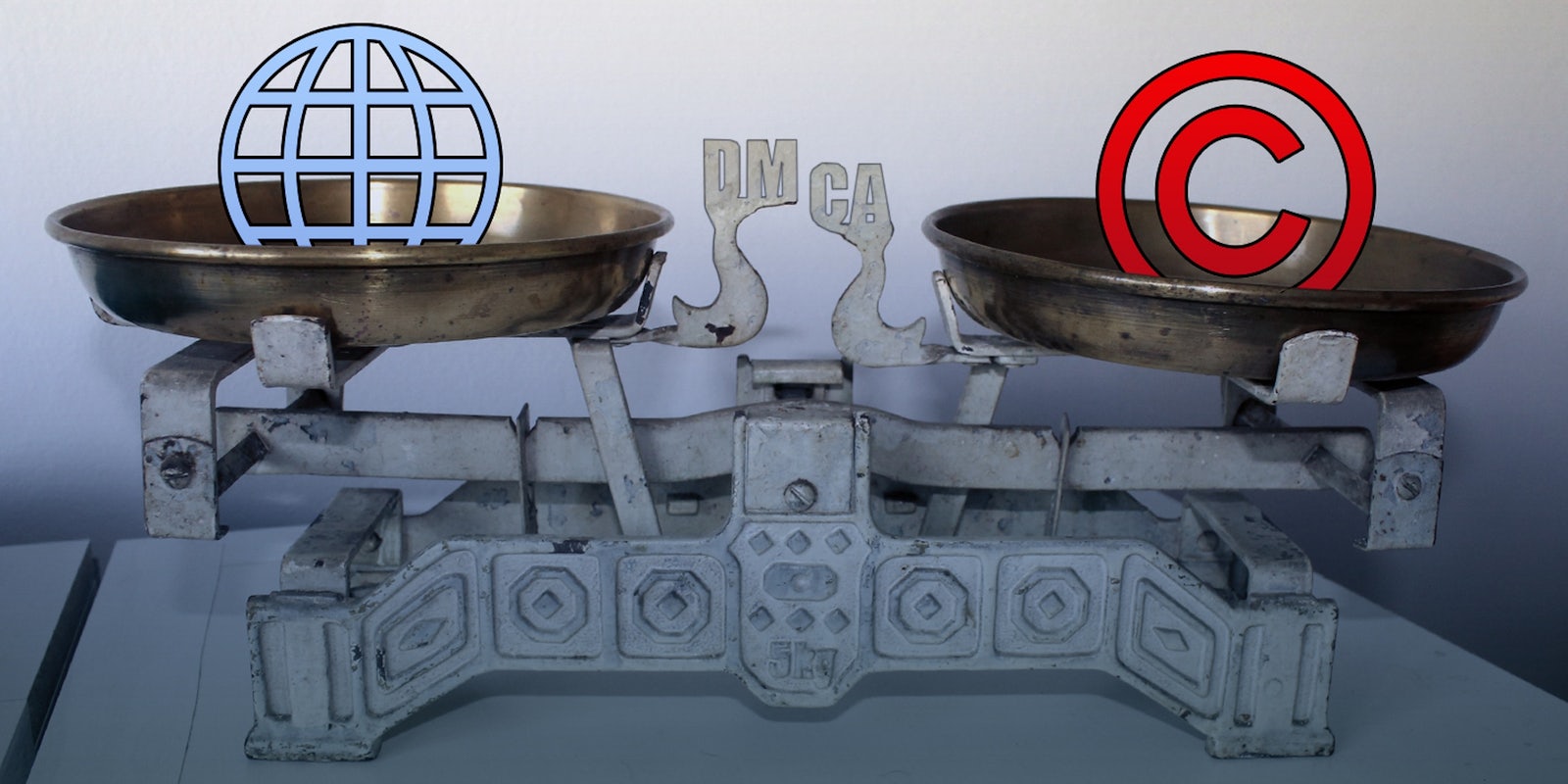

The notice-and-takedown system created by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act provides an essential safe harbor for online services to innovate. This system is the result of an intense series of negotiations between content and tech companies to balance their important competing interests. As such, it’s often hailed as a carefully constructed compromise between the two sides. However, this is not a two-sided issue. By only looking at copyright holders and online services, we neglect the interests of the most populous sector involved in copyright law: the public.

The safe harbors are a safe harbor for online services—hosts of users’ content like YouTube or Facebook. If a user of those services uploads something that infringes copyright, the host’s liability is limited so long as it acts promptly to a takedown notice from the copyright holder. Each side gets something: the copyright holder gets a rapid removal of the infringing content, and the host gets safety from a potentially costly lawsuit. But what happens to the users? Their uploads have been removed, and they’re still potentially on the hook for massive statutory damages in a lawsuit.

This is not just a case of copyright infringers getting what they deserve. Careless or overzealous takedowns have pulled the plug on videos of the Curiosity Mars rover landing, and Chrysler’s 2013 Super Bowl ad (pulled down from its own page by the NFL). More malicious takedowns have tried to squelch reporting on fraud by one researcher, or plagiarism by another. Politicians have faced the specter of frivolous takedowns, too, with the Romney campaign having an ad pulled down, and the Democratic National Convention having its livestream taken down as well. (The Center for Democracy and Technology has compiled a report on the frequent abuse of the DMCA for political purposes.)

If users want their legal content restored to the Internet, they have to go through a process that can actually be fairly burdensome, especially for someone who has not done anything illegal. For example, the DMCA takedown system requires them to provide an address at which they could receive a potential lawsuit, and doesn’t even guarantee a speedy resolution to the dispute.

As flawed and lengthy as it is, users only get the advantage of the DMCA process if the takedown was sent as an official DMCA notice. In many of the above cases, the content wasn’t removed because of the legal process, but because content hosts are trying to meet copyright holders’ demands to go above and beyond what the law requires for the safe harbor. When that happens, hosts aren’t required to pay attention to a user’s protestations of innocence, and the content stays suppressed.

These “above and beyond” efforts can result in hosts overreacting to takedown notices, like one host removing millions of blogs when there was an alleged infringement on one of them, or another taking Adam Smith’s public domain Wealth of Nations off of its site in fear of copyright liability.

Frequently, these errors happen not just because of human overzealousness or malice, but because of the use of automated content identification systems, which will ignore things that would be clear to a human—like the fact that the content was uploaded by an authorized source, or was a fair use.

All of these problems represent, at worst, a system that significantly disadvantages users, and, at best, a law that, if it tries too hard to prevent all uploads, will lead to a system even less likely to treat the public fairly.

Some copyright holders have mentioned that the safe harbors do an imperfect job of keeping infringing content off the Web once it’s been taken down. But no system of laws can lead to perfect enforcement. The practical objective of the DMCA was never to eliminate infringement from the web, just as the practical objective of speed limits is not to ensure that no vehicle ever travels above 60 mph, or for copyright laws to ensure that photocopiers or VCRs could never possibly be abused.

Instead, it was meant as a compromise to the interests of content creators and content platforms. But as policymakers take a fresh look at it, they should be careful to ensure that it doesn’t leave the public out in the cold any more than it does already. If anything, the most necessary changes are those that would protect users from the abuses of the law that have cropped up over the years, by making it easier for users to have legitimate content reinstated promptly and making sure that penalties for bogus takedowns are effective.

The giants of the content and technology industries have worked out a careful balance between their two sides of the issue; we need to make sure that consumers’ rights are balanced against these industry interests as well.

Bartees Cox is the director of public relations at Public Knowledge, a D.C.-based advocacy nonprofit that works for user-friendly online copyright reform.

Photo by Da4Sal/Flickr. | Remix by Jason Reed (CC BY 2.0)