The biggest European wars of the 21st century haven’t raged on the rolling hills of Northern France or the glooming forests of the Ardennes. They’ve played out on a hard drive in a cold server room somewhere in the United States.

That’s where the alternate universe of eRepublik whirs in constant digital existence, a massively popular multiplayer game that’s like a mutant version of Facebook gene-spliced with The Sims and classic military strategy game Risk. Life on eRepublik moves in temporal hyper-drive: Every week is a year in game time. Players are virtual citizens—working, voting, and waging war for nation states. Intercontinental wars are common. Democracy structures civil life.

Released in 2007, the game continues to enthrall more than a quarter-million people, largely in Europe. But it may leave behind a greater legacy than the sustained energy suck of those busy servers.

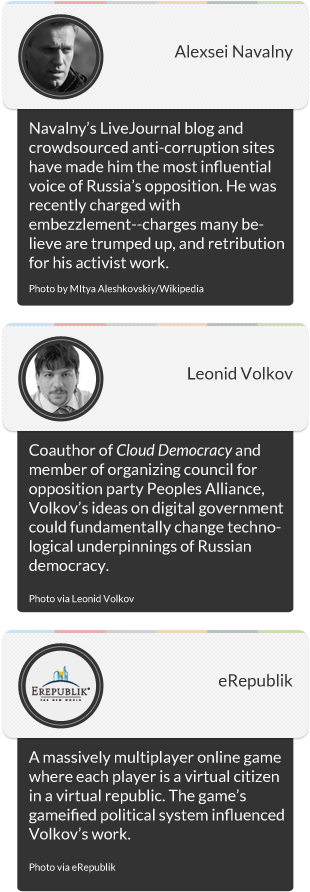

If city councilman, programming expert, and Vladimir Putin-foe Leonid Volkov has his way, it will have helped shape the future of Russian democracy.

—

Volkov and others did not come to eRepublik as Internet novices. They are part of a growing cadre of Web-savvy intellectuals and political reformers currently on the rise in Russia. On Aug. 1, a collection of these opposition leaders took part in what Volkov called “kind of a trend nowadays.” They made a political party.

Born of the massive anti-Putin protests that rocked Moscow in March, the newly minted People’s Alliance may be the best chance for Russia’s opposition to wrest control of the Russian parliament. Founders include core members of activist leader Alexsei Navalny’s inner circle, as well as 31-year-old Volkov—a city councilman from distant Yekaterinburg, a city of 1.3 million in Russia’s sparsely populated Ural Federal District.

Navalny, Volkov, and their ilk are using the Internet to change the game, breaking out of the stranglehold of Russian big media and altering Russia’s political landscape from the wild frontiers of the Internet.

The most famous of Russia’s Web rabble-rousers is Navalny, the 36-year-old lawyer and anti-corruption crusader whose LiveJournal blog has made him the voice and figurative head of the opposition. Volkov calls him the probable “next president of Russia.”

While Navalny’s constant online nagging has made him a thorn in the side of Putin’s United Russia Party, his Web-based projects have yielded far greater influence by exposing corruption and increasing political transparency. The biggest, Rospil, uses crowdsourcing to track public funds, asking the simple question: “Where did the money go?” The group claims to have stopped more than $250 million in questionable public procurements since it was founded. Recent examples include more than $220,000 tabled for “Facebook advertising” and a $93,000 car for a regional courthouse.

The project’s long-term influence, however, will likely be more psychological than financial. Combined, Navalny’s crowdsourced transparency initiatives provide a constant, naked reminder of graft and corruption in an ostensible democracy that to many looks more and more like an autocracy every day. Navalny, for instance, was hit with what many believe are trumped up charges of embezzlement that are intended to silence him.

Volkov, who calls Navalny a “friend,” possesses little of his contempoary’s charismatic power over the opposition. But, informed by a unique background in politics and the Internet, he’s brimming with big ideas. A star student in the computer sciences, Volkov attended Ural State University, where he joined a competitive programming team that took the bronze medal at the 2001 International Collegiate Programming Contest in Vancouver. He graduated with a Ph.D. in mathematics and physics, then joined IT firm SKB Kontour, a company Volkov compared to TurboTax in the U.S.

In 2009, Volkov ran for and won a seat on Yekaterinburg’s city council. Soon he’d sold his shares in SKB Kontour and launched a tech incubator. Meanwhile, he became fast friends with his political consultant Fyodor Krasheninnikov, and the two got sucked into the web technology that would bring all their other Internet-inspired efforts to a head: eRepublik.

Volkov played a farmer; Krasheninnikov took the role of virtual newspaper publisher.

According to eRepublik CEO Alexis Bonte, the game’s politics are “inspired [by] a mix of the democratic systems you would see in normal countries except we have tried to simplify it and make it as direct as possible.”

You can see eRepublik’s political system in some of Volkov’s online political work. His crowdsourcing site, DalSlovo.ru, keeps track of broken (or kept) political promises—a function also found in eRepublik’s political system.

Indeed, beyond these individual projects, the game was the perfect final tincture for the technological and political brew that had been fomenting in Volkov’s mind.

Volkov said his biggest lesson from eRepublik was that democracy could be gamified—a trendy term in tech circles that’s been touted as the solution for everything from financial services to extreme sports. Gamification generally refers to adding game elements (scoring, leaderboards) to pursuits that have nothing to do with games (or fun).

Together Volkov and Krasheninnikov published their treatise on gamified government, Cloud Democracy, in 2011 (available here, in Russian), which may be the most logical structural manifesto for an opposition whose proliferation has been largely dependent on the Internet.

They called for a radical restructuring of democratic governments from the bottom up.

“We believe,” the book began, “that we witness the new era in the history of mankind—the era of limitless direct communications, which would enable the existence of fair, transparent, and just political system.”

At its core Cloud Democracy is about “participation,” according to Volkov. And at its most basic level, that means implementing a purely electronic voting system. Volkov sees this as a direct salve for the deleterious cronyism and centralization of power that typifies Putin’s Russia. It’s also about increasing transparency, about making a huge variety of government metrics available through a centralized online hub.

There are wilder ideas, too.

Volkov and Krasheninnikov suggest a live political trust gauge to provide a constant check on politicians, to make sure no one breaks promises or becomes too cozy in a multi-year terms. After public opinion polls dropped beneath a certain threshold, politicians would get booted from office. Volkov suggested 25 percent.

The feature Volkov would most like to see implemented in a hypothetical People’s Alliance government is what he calls “delegation of votes to experts.” In the same way that you can follow a person on Twitter or like them on Facebook, in a theoretical cloud democracy you could delegate your vote to someone you feel has more expertise on certain legislation. Don’t feel confident on IT matters? Entrust your vote to Volkov, and he’ll vote for you.

You can watch some of Cloud Democracy’s ideas being tested live at Democracy2, a social political platform featuring forums and live voting, which Volkov has opened to the public. The book’s also inspired an active forum—and critics.

GlobalVoices’s Russia correspondent, Kevin Rothrock, has noted that, despite Cloud Democracy’s “great expectations … it perhaps suffers from the elitism that perennially cripples Russia’s democratic reformists.”

He continued:

“In Volkov’s book, for instance, he advocates introducing a voter eligibility ‘filter’ to deny the franchise to any citizens incapable of passing a test on constitutional rights. He writes openly about recruiting ‘active citizens’ into ‘the elite of a new society.’”

There are big hurdles for the People’s Alliance, too.

Putin’s United Russia Party suffered setbacks in the December 2011 parliamentary elections, but it still took 50 percent of the vote and continues to exert huge influence over the electorate and Russia’s major media companies. Putin himself took in a whopping (albeit contested) 64 percent in the presidential elections in March.

And officially, the People’s Alliance doesn’t exist yet. It has six months to convene a founding congress and another six months to set up 42 regional branches before it can officially form as a party.

The group already suffers from internal squabbles as well. Rothrock noted that “rows with Internet-skeptics and eGov-idealists” have been a major feature of the People’s Alliance—all before it’s even officially formed. (Indeed, Volkov is just one of many opposition voices. There’s no guarantee his Cloud Democracy ideals will end up running the party).

And Navalny—the face of the opposition movement—has yet to join the People’s Alliance, limiting his involvement to promotional blog posts.

Still, the party is playing the game smartly. It’s trying to build up support radially, using the opposition’s tried and true method of crowdsourcing to fundraise. It’s also setting its sights on local—rather than federal—elections. Volkov said the first target will be the Moscow city legislature elections in 2014.

“We want to win those elections,” he said. “That’s our goal.”

That’s when the political games really begin.

Illustration by Matt Sisson