In early June, valedictorian Mayte Lara tweeted about her many accomplishments upon graduating from Crockett High School school in Austin, Texas. “Valedictorian, 4.5 GPA, full tuition paid for at UT, 13 cords/medals, nice legs,” she wrote, accompanied by pictures of her on graduation day. It’s the kind of tweet any teen in America would fire off about a significant day in their life.

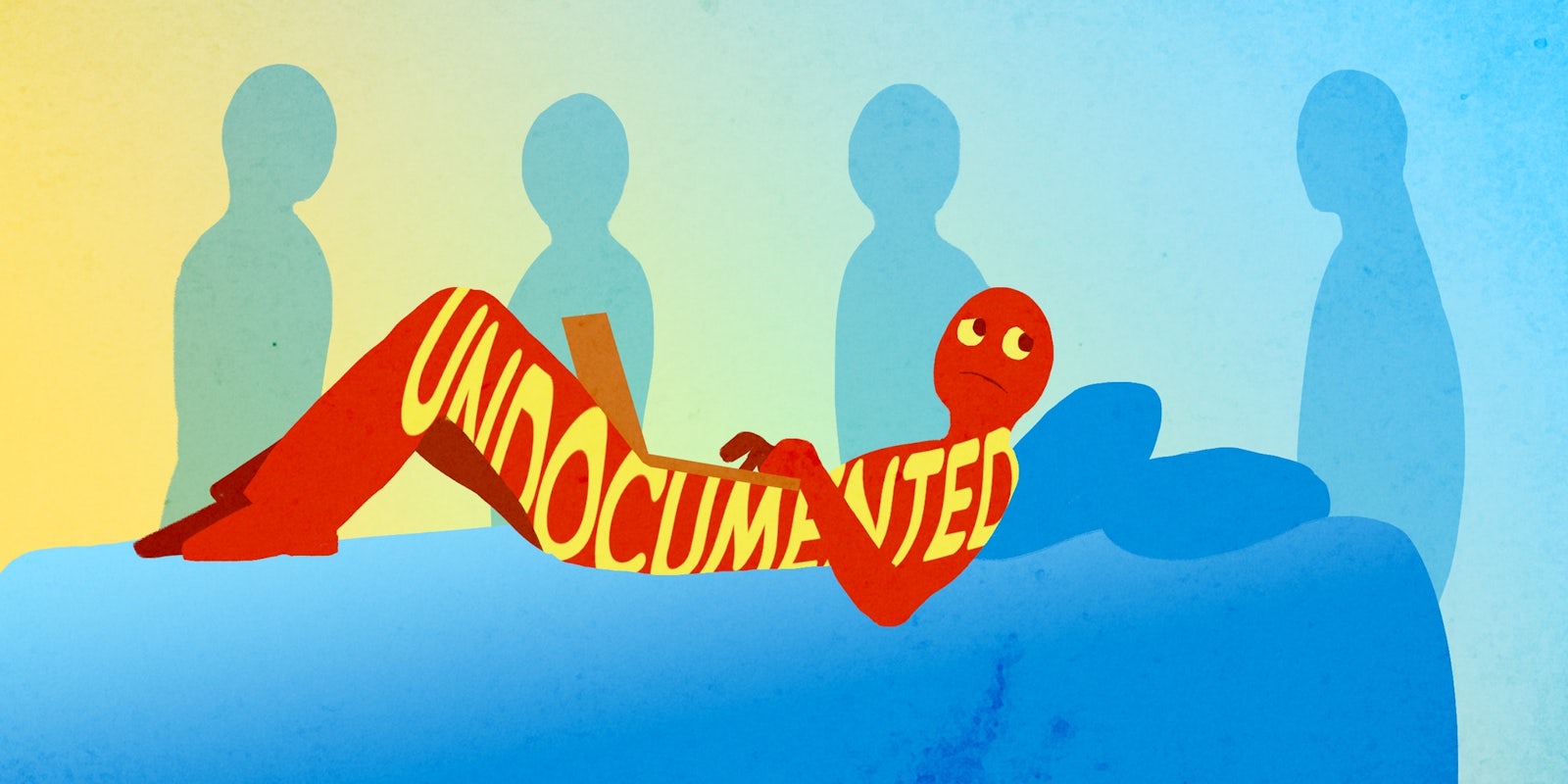

But Lara had one more thing to add: “Oh and I’m undocumented.”

And that’s when the drama started.

Lara instantly became the target of endless vitriol, with people calling for her arrest and deportation. Even if they weren’t attacking, many people and publications (including the Daily Dot) questioned whether going public with her undocumented status was the right move.

Immigration in America is a complicated and controversial issue, one that has become an especially hot-button topic in the current presidential election. Republican nominee Donald Trump has based much of his campaign on the promise of building a wall against the southern border of the U.S., tripling the number of ICE agents, and the “mandatory return of all criminal aliens.” Even though 72 percent of Americans believe undocumented immigrants should be allowed to stay in the country (if they meet certain requirements), the hostility with which undocumented individuals are met when they’re open about their status shows that our country still leans more toward a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.

Despite America’s hedged attitude toward immigration, however, undocumented immigrants are finding ways to survive and thrive—especially online. Many are turning to the internet as a resource for information and finding community support in its little corners, away from the trolls. Many are even using the web as an empowering way to speak out about their status, in spite of the risks.

According to the Center for Migration Studies, there are just under 11 million undocumented immigrants currently living in the U.S.—and they are not a monolith. Melissa Meza, of Diary of an Illegal Immigrant, is one in a handful of bloggers who shares her personal immigration experiences online. Meza was born in Colombia and moved to Venezuela with her family when she was 4 to escape dangerous conditions and scarce jobs. When the same problems plagued Venezuela, she and her mother moved to Miami.

“My mom applied for political asylum, and since I was still under 21, I was ‘blanketed’ by the process since I was technically a minor,” Meza told the Daily Dot over email. “We were refused. Since we were still Colombian citizens, they felt we could move back to Colombia if we wanted to leave Venezuela.”

Meza, now 33, obtained a work permit while her asylum case was in progress, but it expired in 2007. She continued living in Florida undocumented until she eventually met her husband. When she began applying for citizenship through marriage, her husband encouraged her to start blogging about her frustrations, which she has been doing for the past eight years.

On her blog, Meza is brutally honest about the process of obtaining citizenship, including the hurdles that pop up even when you’re following the rules. For instance, the Department of Homeland Security said they had sent Meza and her mother a deportation order, which Meza never received, “which to this date I find curious, since they do love their paperwork.”

“My lawyer informed me that my husband’s application to change my status has been seating [sic] at my local immigration office since August 2009,” she writes in one post from 2011. “Yeah, that long!” In another, she questions just why she’s in her position in the first place. “I have no criminal records, speak perfect English, have not once received help from the government, I am young, healthy and able to work, willing to go to school, smart. Why exactly is the INS so against me?”

“I also felt alone—being illegal can be so alienating,” she told the Daily Dot. “I hoped that maybe if people read what I felt, they would realize that not all of us are complacent with our situations and really do want a legal path to solve our problems. We are not here to take advantage and drain the wealth.”

Meza became a permanent resident in 2012 and attained citizenship in February 2016. Of the experience, she wrote, “I know some people have very heated feelings about immigrants and why we are here and what we do. I know sometimes they don’t know us, our stories, and our reasons. I know sometimes they hate us, sometimes they fear us, and I wish they could see inside my heart and my head and know that I am like so many others out there, and [these others] are trying to get to where I am.”

Overall, Meza says blogging felt “safe” to her, mainly because she didn’t have many readers and didn’t use her real name. She did worry about immigration officials finding her blog, but her mission was too important for her to stop. “I thought about removing the blog, but it felt like such a betrayal to myself and to the people who had read it and who, unlike me, were still stuck in limbo, legally speaking, or even worse forever unable to become legal. So I didn’t delete it,” she said.

“But it did cause me a lot of stress and belly aches and sleepless nights.”

Leezia Dhalla has very little trepidation when it comes to speaking out about being undocumented. Dhalla, who’s undocumented and works for FWD.us, an organization working toward immigration reform, has written about her experiences for the Washington Post, spoke about it in a TEDx talk, and tweets about it on the regular. One of the biggest issues she speaks about is the idea of a “path to citizenship.” According to many undocumented immigrants, that “path” is either unavailable or entirely mythical.

“People talk about how immigrants need to get back in line, but it’s not as simple as that,” says Dhalla. “There is no clear line. That’s what a lot of conversations miss. How do we create applications so that people are able to get ‘in line’?”

However, she also talks about the everyday frustrations of being undocumented. For instance, trying to return items to CVS without a driver’s license.

https://twitter.com/AskLeez/status/742515503407599616

https://twitter.com/AskLeez/status/753039731622088708

“I think that when we talk about immigration, we’re not talking about somebody who crossed the border two months ago. We’re talking about a group of 9 million people who, for over a decade, this has been their home, this is where their schools are, and their friends are, and where their careers are—and it’s important to keep that in mind.”

Dhalla says that programs that offer temporary protections, like Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), have made her less fearful to speak out about her struggles. “I have a Facebook page, I have a Twitter page, I have a Yelp account I check in to,” said Dhalla. “It’s very easy to track me online. If the government really wanted to, they could find me. They mailed me a letter to my house. So if the government already knows, or could easily do a search for you online, then why is there such a stigma to not say this out loud? Why is there so much fear?”

Fear, however, isn’t a singular idea: By speaking out online, there is the fear of deportation, which may or may not occur often in reality; and the fear of harassment, which is absolutely a thing that happens. And then, as evidenced by the abuse lobbed at valedictorian Mayte Lara, there is the harassment that becomes so overwhelming, the fear of deportation suddenly seems much more real—not just to the individual but to everyone in a similar situation who’s watching.

“It’s very easy to track me online. If the government really wanted to, they could find me. They mailed me a letter to my house. So why is there such a stigma to not say this out loud? Why is there so much fear?”

As soon as Lara boldly spoke about her status, people started calling for her to be “returned to her country”—and for her death. She shut down her Twitter immediately and stayed quiet for almost a month. Fear and shame do their best work hand-in-hand with silence.

Martine Kalaw, a consultant and immigration blogger born in Zambia who found out she was undocumented after her mother died, says she understands how the process can shame the majority of undocumented immigrants into silence. Kalaw says blogging about one’s immigration experiences can bring scrutiny from peers more than anything else. “The undocumented immigrant story is about your life. So in order to get sympathy, you have to expose everything about your life. That’s not easy.”

It gives people permission to pry—and to judge if they believe you’re not going about something in the correct way or with the correct tone. Kalaw spoke about feeling the need to present herself as perfect through her fight for documentation. “You feel like you’re not allowed to complain,” she said, lest the answer is, “Well, get out. If you’re so unhappy, then why are you here?”

Gabi Garcia Cruz, on the other hand, says blogging has given her a way to “reclaim the narrative” about what undocumented life looks like. She says she found strength in coming forward about her undocumented status as a student. “Undocumented students specifically often only have this outlet to express what they feel,” she told the Daily Dot. “And even during my time, I never had the opportunity to share my story publicly until later on, when social media was something that developed more.”

Garcia Cruz acknowledges the risks in speaking out but views it as almost a responsibility for undocumented immigrants. “I think that for undocumented students to change how they are viewed, they have to tell their story,” she says. “Not only so that the narrative can change—because right now the narrative is being controlled by other people who use fear as a mechanism of power—but more importantly, for yourself.”

Citizenship is essentially giving people a space where they belong, says Garcia Cruz. Though many undocumented immigrants may feel like they’re in limbo, like their life is out of their hands, these shared stories on the internet can connect them.

Even Lara, the valedictorian, is back online, tweeting mostly about starting college, with an occasional retweet from those who stand in support with her vocalizing her status.

“It was tough for me to come out as undocumented to my friends in high school,” one Twitter user wrote to Lara after her tweet went viral. “Thanks for being a source of strength for others.”