When I was a young boy, I’d travel with my mother to visit a small grave in a hidden cemetery in the English countryside. I was there for manual labor—removing weeds, putting in new flowers, and tending to a small burial site that belonged to a person I had never met. Every time we went, my mother would break down in tears. It was her sister’s grave, my aunt, Olivia Dahl.

Olivia caught measles in 1962, just a few years before a vaccine had become available. My mother said the illness progressed much like any other measles case, horrible to experience but carrying a very slim chance of becoming more severe. Except one morning, while my grandfather tried to help her make toys out of pipe cleaners, something seemed wrong. Olivia could not coordinate her hands. She appeared weak. Soon she lost consciousness. Doctors could not save her.

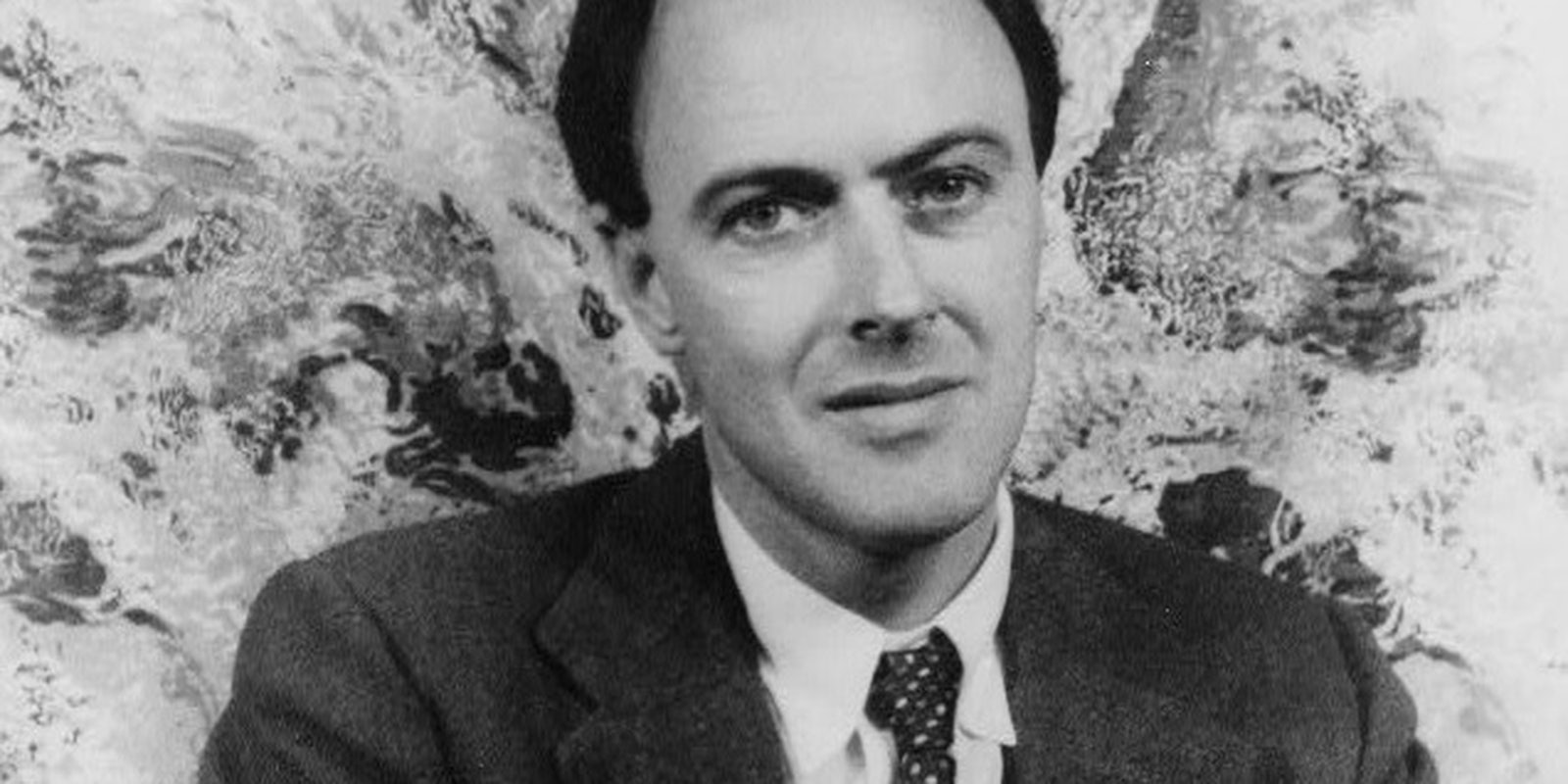

This event led my grandfather, the author Roald Dahl, to write a letter in 1988, urging families to vaccinate their children. Over the past few days, the vaccination debate is making headlines again, and my grandfather’s letter has gone viral.

“Are you feeling all right?” I asked her.

“I feel all sleepy,” she said.

In an hour, she was unconscious. In twelve hours she was dead.

Olivia was unlucky. Her case was one of the very few that progressed into something much more serious, something fatal. Measles encephalitis—when the measles virus spreads into the spine, and then the brain—occurs in 0.1 percent of cases. I will leave it to my grandfather’s diary to describe what happened next. (Mervyn was the family’s doctor, and Pat was my grandmother, Patricia Neal.)

“Got to hospital. Ambulance went to wrong entrance. Backed out. Arrived. Young doctor in charge. Mervyn and he gave her 3mg sodium amatol. I sat in hall. Smoked. Felt frozen. A small single bar electric fire on wall. An old man in next room. Woman doctor went to phone. She was trying urgently to locate another doctor. He arrived. I went in. Olivia lying quietly. Still unconscious. She has an even chance, doctor said. They had tapped her spine. Not meningitis. It’s encephalitis. Mervyn left in my car. I stayed. Pat arrived and went in to see Olivia. Kissed her. Spoke to her. Still unconscious. I went in. I said, ‘Olivia… Olivia.’ She raised her head slightly off pillow. Sister said don’t. I went out. We drank whiskey. I told doctor to consult experts. Call anyone. He called a man in Oxford. I listened. Instructions were given. Not much could be done. I first said I would stay on. Then I said I’d go back with Pat. Went. Arrived home. Called Philip Evans. He called hospital. Called me back. ‘Shall I come?’ ‘Yes please.’ I said I’d tell hospital he was coming. I called. Doc thought I was Evans. He said I’m afraid she’s worse. I got in the car. Got to hospital. Walked in. Two doctors advanced on me from waiting room. How is she? I’m afraid it’s too late. I went into her room. Sheet was over her. Doctor said to nurse go out. Leave him alone. I kissed her. She was warm. I went out. ‘She is warm.’ I said to doctors in hall, ‘Why is she so warm?’ ‘Of course,’ he said. I left.”

This event scarred my family, particularly my grandfather. My mother used to tell me that at Olivia’s funeral she was convinced it was all a cruel trick and that her sister would simply sit up from her coffin to end the awful situation.

Despite the sadness, it did spur my grandfather to spend the rest of his life telling people why not vaccinating your children is one of the worst mistakes a parent can make. While Olivia did not have the luxury of a vaccine, society now does, and to forsake that is one of the greatest crimes one can commit. Later, reflecting on Olivia’s death, he wrote about the vaccine in terms of necessity:

Believe me, it is. In my opinion parents who now refuse to have their children immunised are putting the lives of those children at risk.

Even today, when I read about those who refuse to vaccinate their children, it reminds me of the aunt I never met, and the grave I helped tend to. It is desperately sad to think that despite more than 50 years of medical advancement, people can still meet the same fate as Olivia. My grandfather felt the same. He kept her spirit alive in his books.

“All school-children who have not yet had a measles immunisation should beg their parents to arrange for them to have one as soon as possible.

I dedicated two of my books to Olivia, the first was ‘James and the Giant Peach.’ That was when she was still alive. The second was ‘The BFG’, dedicated to her memory after she had died from measles. You will see her name at the beginning of each of these books. And I know how happy she would be if only she could know that her death had helped to save a good deal of illness and death among other children.”

Photo via Roald Dahl/Library of Congress