For many consumers, the Environmental Working Group is a godsend, using science to slice through a fog populated by unpronounceable ingredients on food labels, cosmetics labels, and pretty much anything else at the local store. And for the roughly 70 scientists, lawyers, lobbyists, and activists behind EWG, it also feels like important work—they are a watchdog over an industry that largely operates without any real government oversight. Without them, they say, consumers would pretty much be in the dark about what products they’re putting on their faces and in their bodies every day.

But for industry chemists, the EWG, whose ratings of over 62,000 products can be found online, is more than a thorn in their side. The EWG represents a nuisance that, in industry eyes, stokes unnecessary fears about the safety of product ingredients.

Chief among scientists’ complaints about the EWG is that its safety recommendations err too far on the side of caution. In particular, its Skin Deep database, in which it rates the safety of cosmetic products, is a sore point for a lot of the cosmetic industry chemists the Daily Dot spoke with. They note that the watchdog’s scoring system is informed by some expertise but is largely arbitrary.

Which raises the question: Is there anything to lose by being too cautious when it comes to what you put on your body? What are cosmetic wearers missing if they don’t heed the EWG’s warnings?

Well, whatever the FDA isn’t catching, for starters. “The average consumer [in the U.S.] is under the misapprehension that the Food and Drug Administration is making companies substantiate the safety of products before they sell them, and in fact they’re not, and that’s a pretty scary thought,” Tina Sigurdson, a staff attorney at the EWG told the Daily Dot. “So I think it’s important to put this information in consumers’ hands so they can make informed decisions as well as push for more meaningful government oversight in the safety of cosmetics.”

Cosmetics companies are not beholden to the FDA for approval before taking a product to market. However, according to the FDA’s website, “Under the law, cosmetics must not be ‘adulterated’ or ‘misbranded.’ For example, they must be safe for consumers when used according to directions on the label, or in the customary or expected way, and they must be properly labeled. Companies and individuals who market cosmetics have a legal responsibility for the safety and labeling of their products.”

The EWG argues there’s no compelling reason to trust cosmetics companies to put the consumer’s long-term safety first. Acute reactions like skin irritation and allergies are easy enough to test in a laboratory. But cancer is slow to develop, and its cause is often hard to pinpoint.

“There is no smoking gun,” Sonya Lunder, a senior analyst at the EWG, told the Daily Dot, said about the fraught nature around the idea of “finding a cure for cancer.” “What is the incentive for the industry to do anything?”

Lunder hits on a valid point: Studies on the long-term effects of products in relation to cancer need to be conducted in real people for many years. Even then, researchers can only find a correlation—not a cause-and-effect relationship—between any one ingredient and a disease like cancer.

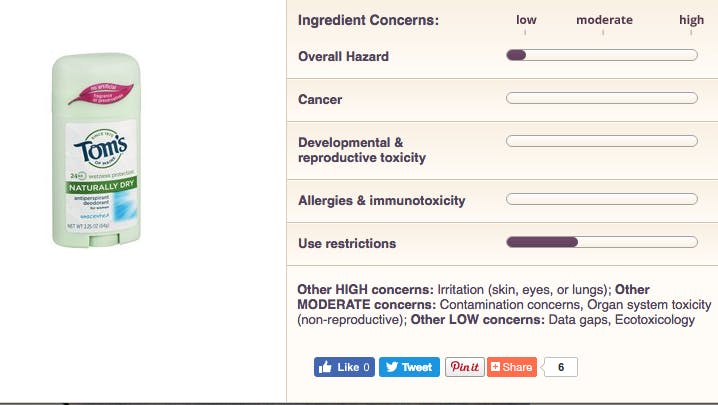

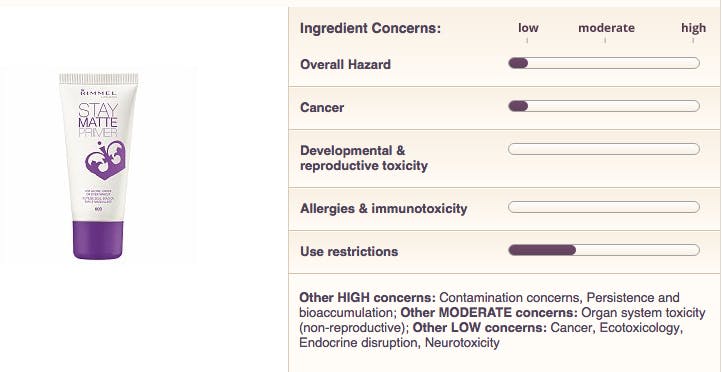

So what the EWG does is look at all the ingredients and the literature. It may find that one ingredient in your favorite lipstick has been shown to disrupt the hormonal cycle in laboratory rats, or that repeated exposure to another ingredient is associated with cancer in women. It weighs the evidence and tries to boil it down into one, easy-to-understand score, an aggregate of the individual scores of its ingredients. A product that gets a 10 represents a high degree of danger, whereas a 1 or 2 would pose nearly no risk to the consumer.

For example, this matte-finish primer by Rimmel gets an overall score of 1, showing it to be nearly inoffensive. However, the EWG still lists all the ingredients within the product anyway that might be concerning. On the other end of the spectrum, L’Oreal Preference hair dye gets a hazard score of 10, since it contains many ingredients associated with skin irritation, allergies, and cancer—although the data available is limited.

In other words, if a consumer knows they’re highly sensitive to a particular ingredient, a tool like the Skin Deep Database is extremely helpful. It can save them from hives, irritation, or much, much worse.

EWG skeptics, however, say the watchdog group is borne from bias and its mission is a witch hunt of sorts. “Their whole existence relies on propagating myths about cosmetics not being safe,” said Perry Romanowski, a cosmetic chemist behind the Beauty Brains blog.

“People will often compare it to the tobacco industry,” he continues. “But the thing about tobacco is that there’s no safe use of tobacco… That’s not the same for cosmetics. The cosmetics industry could replace any chemical they want. They’re just not unsafe.”

Romanowski argued what the EWG is missing is nuance. He used formaldehyde as an example. He said that the EWG assigns a hazard score to formaldehyde in cosmetics, which is often used as a preservative. And in large quantities, or when it’s inhaled as a gas, formaldehyde is certainly dangerous to human health.

In an article on the EWG’s website titled, “Exposing the Cosmetics Cover-up,” it writes:

Personal care products that contain formaldehyde make an unnecessary contribution to an individual’s exposure to this chemical—particularly since research shows that cosmetic products can release small amounts of formaldehyde into the air shortly after they are applied. Formaldehyde is most dangerous when inhaled.

But the research it links to in that statement, available here, says that formaldehyde released by personal care products (including cosmetics) “poses no risk to human health.”

“[The EWG has] this binary thing like: This chemical’s bad, this chemical’s good. The reality is, depending on your perspective, all chemicals are bad and all chemicals are good,” Romanowski said. He cited the trite-but-apt example of water: Water is a wonderful chemical composed of hydrogen and oxygen that we need to sustain life. But even drinking too much water can lead to health consequences, and even death.

“The EWG has this binary thing like: This chemical’s bad, this chemical’s good. The reality is, depending on your perspective, all chemicals are bad and all chemicals are good,” says one critic.

That’s an inherent problem that crops up when doing literature reviews. The EWG doesn’t test cosmetics itself in a lab, but simply figures out if an ingredient is present and rates that ingredient. The FDA states cosmetics are required to label their products with the ingredients in it, in descending order of predominance, but they don’t have to label exact quantities. This protects their proprietary recipes, but leaves both consumers and watchdog groups clueless as to just how much of any one ingredient is in the products they use. Cosmetic chemist Stephen Alain Ko told the Daily Dot via email that without knowing the concentration of an ingredient, it’s hard to know how it may affect a person using it.

So for people who haven’t been diagnosed with a particular sensitivity, or are just highly concerned with their own health, the EWG can be viewed as less of a friend and more of a predator—one that preys on fear, some chemists worry.

“We have an innate propensity to be chemophobic,” said James Kennedy, a chemistry teacher at the Haileybury Institute in Australia. “We are naturally wary of risks imposed by other people.”

Chemophobia is not a diagnosable mental illness, but just a loose term some chemists use to describe fear of chemicals, represented by common refrains like, “Don’t eat any foods with ingredients you can’t pronounce.” But of course, every food has ingredients you can’t pronounce, and literally everything is made up of chemicals.

Kennedy thinks chemophobia is related to our rampant distrust of corporations regarding consumer safety, and is partly due to precedence.

“The last generation of chemists left us with this horrible mess. Their reputation is a horrible mess,” Kennedy said. “They made agent orange, they made thalidomide, they made asbestos. And now we have to pick up that reputation. And even though many amazing compounds have been made since then, that tainted image still remains somewhat.”

You could say trust between consumers and the industry is still in the growing pains phase—and we’re all just searching for some reasonable, unbiased information about what we should be putting on our skin. However, when the EWG attacks a product, industry scientists often aren’t allowed to or encouraged to speak with reporters to retort or clarify what had been said. Companies instead rely on public relations officers to give statements about safety, but this semi-robotic practice may not help engender trust in a corporation—though it’s not necessarily a sign that something’s amiss.

“The thing is, research does continue to go on,” Romanowski said, emphasizing that cosmetics companies, regulatory agencies, and the FDA do keep their eyes peeled for signs an ingredient is unsafe. In the meantime, the EWG will also be on the lookout to fill in the gaps—whether they need filling or not.