If you paid any attention to the hype surrounding HBO’s True Detective earlier this year, you probably noticed that the series’ numerous literary references got extensive media play. Above them all was a recurring reference to the series as “Lovecraftian.” But what exactly linked this police drama to the Dread Cthulhu? Can you just slap the Lovecraft label onto anything these days?

Not exactly. Like its predecessors in the niche genre of Lovecraftian fiction, True Detective had its hooks into a few classic tenets of horror that are finding a resurgence lately, both in the Internet’s cult love for Cthulhu and in the recent revival of Weird Fiction.

Lovecraft’s tales of terror inspired Alien designer H.R. Giger and gave us one of the most enduring modern monsters of the 20th century. They also gave us the gory cult horror classic Reanimator and the Necronomicon, a book so storied many people don’t realize it’s not actually real.

With this week’s new Legends of Cthulhu card game already smashing its Kickstarter goal, we thought it was the perfect time to drench ourselves in pig blood and summon the Great One to reveal Lovecraft’s secrets unto our media outlet. Steady on for your encounter with the true and ultimate horror, and all the things that make Lovecraft such an enduring force in fiction today.

What’s a Lovecraft?

Lovecraft refers to H.P. Lovecraft, a turn-of-the-20th-century author whose works were a key part of the early days of pulp-based science fiction, fantasy, and horror. A creative egalitarian, Lovecraft borrowed tidbits of story elements and influence from other authors, like the fabled city of Carcosa, which passed from Ambrose Bierce to Robert W. Chambers to Lovecraft and authors after him until it showed up in Louisiana in the climactic final episode of True Detective, and other unknown locations since.

Lovecraft also eagerly encouraged other authors to borrow and build on his works, which helped foster a thriving tradition of Lovecraft fanfiction, remixes, and crossover elements. It didn’t do much for him financially—he died penniless and unknown—but he fostered such a loyal cult following of horror aficionados that over time his renown grew. Today he is considered one of the most influential speculative fiction writers of the 20th century.

What’s “Weird Fiction?”

Weird Fiction refers to a specific kind of horror that harkens back to the pulpy days of Lovecraft and the magazine in which he was most frequently published, Weird Tales. The body of Lovecraft’s work consists primarily of short stories and novellas, all of which are freely available online today. The basic characteristics of Lovecraft’s fiction are traits shared by many of those writers who came both before and after him:

- Gravely serious, detail-rich descriptions of untold horrors, often blended with existential wonder:

GIF via goingsomewhereisnothere

- Brief, terrifying encounters with unholy, otherworldly phenomena, which makes the narrator (and the reader) feel as though they have glimpsed the edge of a vast and overwhelming darkness. “I have looked upon all that the universe has to hold of horror,” Lovecraft writes in “The Call of Cthulhu.”

GIF via onthescreenreviews.com

- References to mythical or fictional cities, people, places, or things, such as Lovecraft’s Necronomicon or Chambers’ terrifying play The King in Yellow. The implication is usually that these myths or esoteric creations are real and accessible to a certain number of doomed explorers, many of whom write from a position of horror after journeying to the lost city, or finding and reading the forbidden book, etc.

Photo via goodlolz

- Narrators who cannot escape unscathed from what they have encountered, and who either gradually go mad from the encounter, die, commit suicide, or transform into some otherworldly being or monstrous creature themselves. In Lovecraft, the safe option is usually, but not always, madness.

To be clear, Lovecraft didn’t invent weird fiction, which was a style already kicking about when he came along. But he did coin the term “Weird Fiction,” and codified much of it. Here’s how he described all the elements mentioned above in his 1933 essay on the subject:

“My reason for writing stories is to give myself the satisfaction of visualising more clearly and detailedly and stably the vague, elusive, fragmentary impressions of wonder, beauty, and adventurous expectancy which are conveyed to me by certain sights (scenic, architectural, atmospheric, etc.), ideas, occurrences, and images encountered in art and literature. I choose weird stories because they suit my inclination best—one of my strongest and most persistent wishes being to achieve, momentarily, the illusion of some strange suspension or violation of the galling limitations of time, space, and natural law which for ever imprison us and frustrate our curiosity about the infinite cosmic spaces beyond the radius of our sight and analysis.”

Weird fiction often blurs the lines between horror and fantasy, and while the term usually refers to the vintage writers between the late 19th century and the 1930s, it’s also a good description of many of the works of China Mieville, Clive Barker, and even somber modern horror masterpieces like House of Leaves.

Of course, none of them quite have what Lovecraft has—the monster at the center of all his nightmares.

Who is the Dread One?

Like all the great and terrible horrors, the Dread One has many names: Great Cthulhu, Tsathoggua, and Him Who is not to be Named (yes, like Voldemort).

C-what-thu?

Cthulhu. Traditionally, Cthulhu has no “correct” pronunciation because it’s an unknown ancient tongue meant to invoke horror, hence why he is not to be named.

In reality, anecdotally Lovecraft himself pronounced it “Cut-a-loo,” but in our modern age of reverence for the Great One, we generally pronounce it “ka-thoo-loo.”

So what is this Ka-thoo-loo?

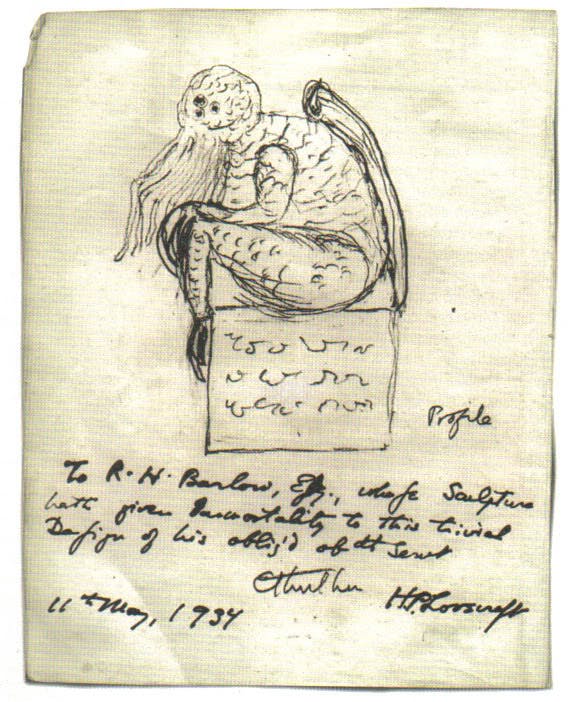

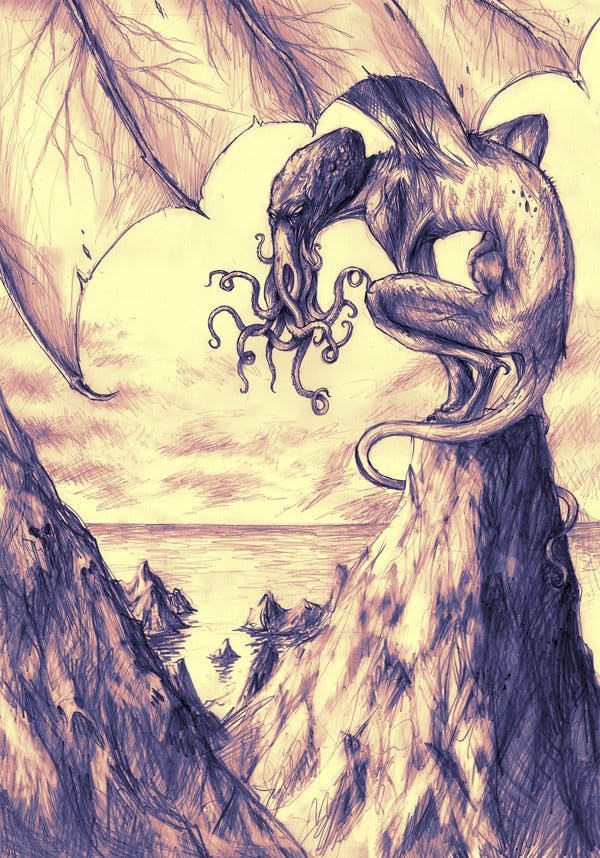

We meet him first in the 1928 short story “The Call of Cthulhu,” featured in the classic fiction magazine Weird Tales. He first appears as a mysterious stone statue carved in homage to some alien god:

A monster of vaguely anthropoid outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind. This thing, which seemed instinct with a fearsome and unnatural malignancy, was of a somewhat bloated corpulence, and squatted evilly on a rectangular block or pedestal covered with undecipherable characters. The tips of the wings touched the back edge of the block, the seat occupied the centre, whilst the long, curved claws of the doubled-up, crouching hind legs gripped the front edge and extended a quarter of the way down toward the bottom of the pedestal. The cephalopod head was bent forward, so that the ends of the facial feelers brushed the backs of huge fore paws which clasped the croucher’s elevated knees.

So basically, Cthulhu is a giant winged monster with a tentacle face. Here’s how Lovecraft thought his terrifying stone sculpture looked:

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

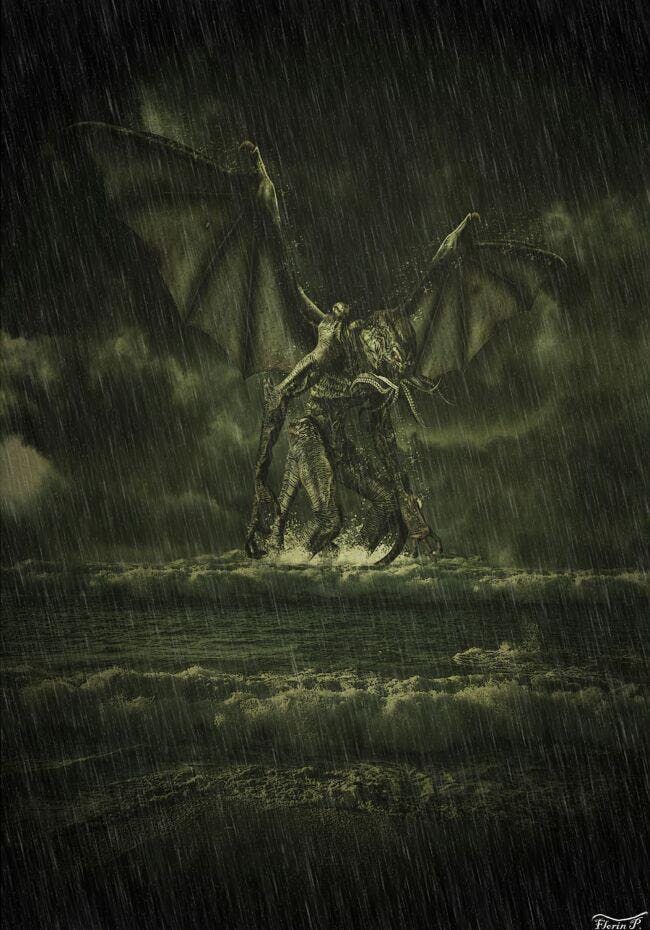

Cute, right? But as “The Call of Cthulhu” continues with a voyage to Southern Pacific waters, it becomes evident that the Great Old Ones, namely Cthulhu and his band of slumbering monsters, are alive in the Antarctic Sea and planning your doom:

[T]he men sight a great stone pillar sticking out of the sea…a coastline of mingled mud, ooze, and weedy Cyclopean masonry which can be nothing less than the tangible substance of earth’s supreme terror—the nightmare corpse-city of R’lyeh, that was built in measureless aeons behind history by the vast, loathsome shapes that seeped down from the dark stars. There lay great Cthulhu and his hordes, hidden in green slimy vaults and sending out at last, after cycles incalculable, the thoughts that spread fear to the dreams of the sensitive and called imperiously to the faithfull to come on a pilgrimage of liberation and restoration.

The important things to note here are:

A) There’s a lost city at the bottom of the world called R’lyeh.

B) Cthulhu, even while slumbering ominously beneath the deep, can infiltrate your mind and drive you mad with the summons to join him in his lair of darkness.

Photo via horrordimensions

The story goes on to describe the lost city as a nightmarish blend of non-Euclidean geometry and bizarre shapes and structures, a “dripping Babylon of elder daemons.”

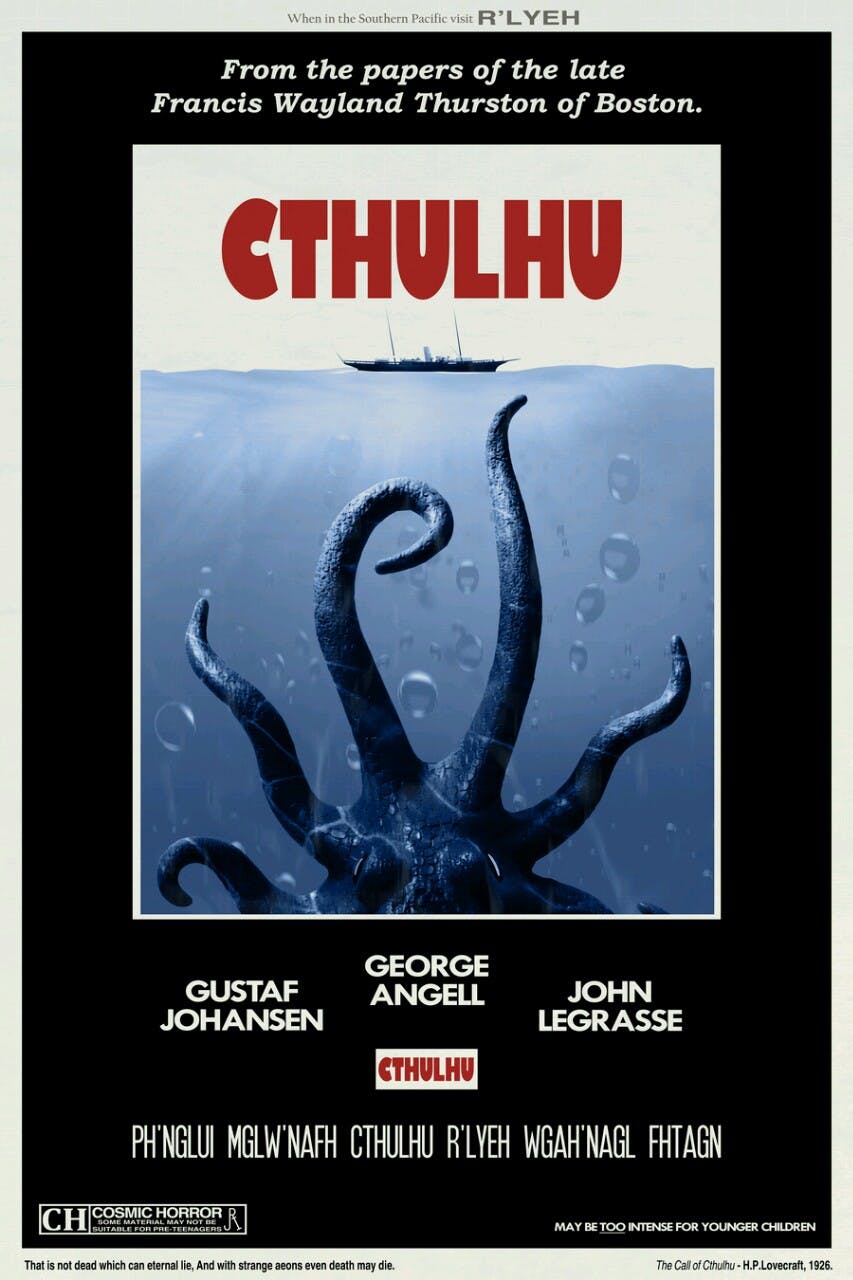

Images of Cthulhu proliferate our modern world, most of them fixated on the moment when he rises from the deep to great, doomed “Call of Cthulhu” ship The Alert.

Illustration by Rafael Badan/deviantART

Photo via trapjaw

Illustration by neriak/deviantART

Today, Cthulhu’s followers are predictably legion, though most of them are really just Lovecraft fans. A few devout believers, however, have formed an actual Cult of Cthulhu, based on Lovecraft’s assertions that the fictional Cthulhu had a strong cult of human devotees. The modern-day Cult of Cthulhu was founded in 2008 by Darrick Dishaw, a.k.a. High Priest Venger Satanis, who comfortingly told Before It’s News last year that he was “actively trying to push our slimy green agenda. Madness is only a form of alien sanity.”

As you can see from the (possibly NSFW) Cthulhu priest cosplay below, the cult is alive and well:

Photo via ianference

Who are the other Great Old Ones?

It’s not necessarily specified that Cthulhu and the other Lovecraftian monsters are pals, but a number of figures recur again and again throughout his stories. For example, in “The Whisperer in Darkness,” the narrator’s mysterious host hears the Dread One being summoned, along with other mysteries of the deep.

Many of these monsters have names. Here they are, in descending order of scary:

Yog-Sothoth

A god of the cosmos and a “limitless being,” Yog-Sothoth may or may not exist on the edge of consciousness, between this universe and the next. Yog-Sothoth appears most prominently in “The Dunwich Horror.” It is often depicted as having many eyes, probably because of its all-knowing state. It probably looks nothing like this guy, but we still like to dream:

Screengrab via Fanpop

Shoggoth

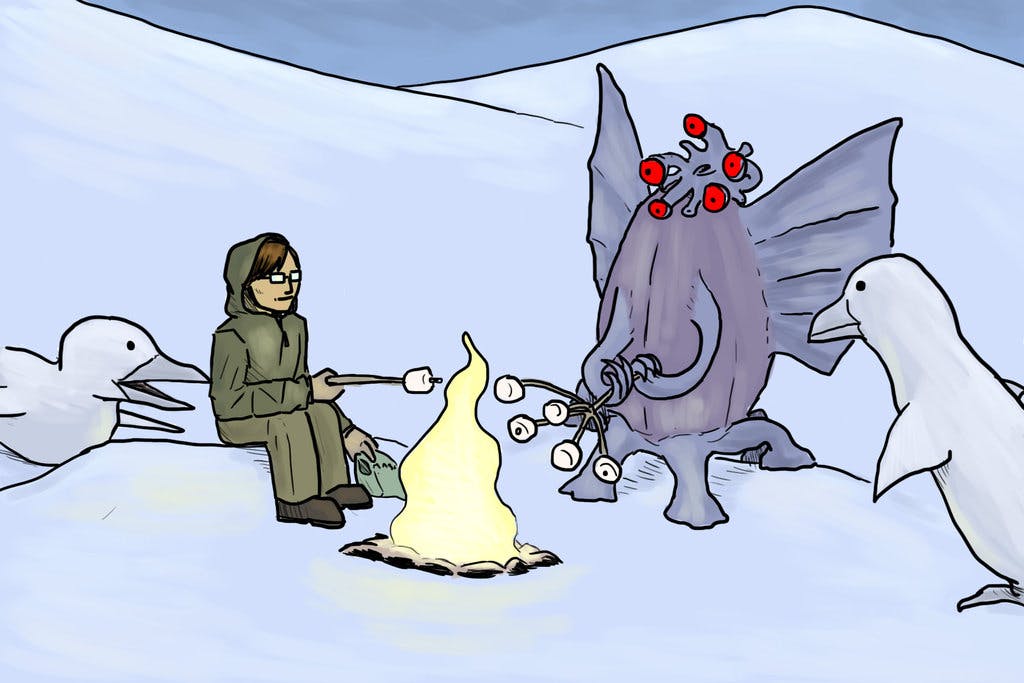

Shoggoths make appearances in numerous Lovecraft stories, most notably “At the Mountains of Madness,” where its terrible nature is revealed. Made of eyes, it’s basically a slimy, green, putrid blob. Its greatest evil? Murdering the helpless blind albino penguins that live beneath the Antarctic:

We were on the track ahead as the nightmare plastic column of foetid black iridescence oozed tightly onward through its fifteen-foot sinus; gathering unholy speed and driving before it a spiral, re-thickening cloud of the pallid abyss-vapour. It was a terrible, indescribable thing vaster than any subway train—a shapeless congeries of protoplasmic bubbles, faintly self-luminous, and with myriads of temporary eyes forming and unforming as pustules of greenish light all over the tunnel-filling front that bore down upon us, crushing the frantic penguins and slithering over the glistening floor that it and its kind had swept so evilly free of all litter.

Illustration by scythemantis

Night-Gaunts

These literal night terrors appeared in only one Lovecraft story, but they left quite an impression. Oily, demonic creatures with bat-wings and no faces to speak of, they actually emerged from Lovecraft’s childhood nightmares: “When I was 6 or 7,” he wrote in a letter once, “I used to be tormented constantly with a peculiar type of recurrent nightmare in which a monstrous race of entities (called by me ‘night-gaunts’…) used to snatch me up [and] carry me off.” Color us creeped out.

Illustration by neriak

Azathoth

A “demon-sultan” who “rules all time and space from a curiously environed black throne at the centre of Chaos,” Azathoth is considered the greatest and most terrible of all the gods, a “mindless entity” ruled by a love of evil.

But really, his main scare tactic, as we learn in “The Dreamquest of Unknown Kadath,” just seems to be shitty band music:

“[Azathoth] gnaws hungrily in inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond time amidst the muffled, maddening beating of vile drums and the thin, monotonous whine of accursed flutes; to which detestable pounding and piping dance slowly, awkwardly, and absurdly the gigantic ultimate gods…”

Oh, and he can also create fathomless black holes and blot out your existence at will. No big deal.

Illustration by xlegandariumx

The Elder Things

In “At the Mountains of Madness,” Lovecraft spends lots of time talking about the “elder earth” and the ancient monsters that bubbled out of the cosmos to create the earth “as jest or mistake.” Yog-Sothoth, Shiggoths, the “primal jelly,” and “the eyes in darkness” are all given as examples of these creatures, along with a host of general alien and primordial terrors. But we prefer to think of them as cuddly camping companions, along with the aforementioned albino penguins:

Illustration by mctalon

Tsathoggua

Tsathoggua is an evil, giant, black toad-god. Cool. Even cooler, Tsathoggua is a creation of Lovecraft’s friend Clark Ashton Smith, who wrote original stories as well as stories within the Cthulhu Mythos alongside Lovecraft in Weird Tales. Lovecraft worked Tsathoggua into his own stories multiple times.

Photo via loneanimator

Other creations Lovecraft had in his terrifying Rolodex of ancient beings: sentient fungi, hideous fish-humans who dwell underwater for eternity, an ancient pharoah/monster who’s probably an alien reptiloid, and a terrifying fertility goddess, Shub-Niggurath.

Landscapes of horror

In addition to the gamut of monsters with which he populated his stories, Lovecraft used a number of recurring details and fictional locations to build his universe. The Arkham Asylum, which later lent itself to Gotham City’s Arkham Asylum in the DC Comics Batverse, was a familiar Lovecraftian haunt. It appears as the name of the fictional city of Arkham, Mass., and as that town’s asylum, and also as the name of a boat venturing to the Antarctic in “At the Mountains of Madness.”

Folks ventured to the Antarctic a frequent amount in Lovecraft’s stories, although he made it clear horror could be found anywhere, such as in his fictional New England settings of Arkham, Mass., rural upstate Vermont (“The Whisperer in Darkness”), and the other fictional town of Dunwich, home to the “Dunwich Horror” and the fictional Miskatonic University, where a deadly copy of the Necronomicon is housed.

What’s the Necronomicon?

The Necronomicon is a fictional grimoire. While grimoires are real books written to house spells, names of demons, and serve generally as creepy magical record-keeping, the Necronomicon is an entirely fake creation of Lovecraft’s. It appeared again and again in his work, the Book of the Dead, which held the key to summoning the Great Old Ones and basically unleashing the untold evil ancient powers of the universe.

![]()

Photo via ryoshi-un

The Necronomicon has become such a standard part of modern mythology that it seems as though it has always been with us. But then Lovecraftian mythos has snuck its way into just about every modern horror concept, from insane asylums to occult symbols. His influence has popped up everywhere from The Evil Dead to Ghostbusters to Harry Potter to Pirates of the Caribbean to Welcome to Night Vale.

GIF via tentacly-davy

Lovecraftian fiction is alive and well today, with countless adaptations of his works, new authors writing weird fiction, and the threading of Lovecraftian’s brand of cosmic horror into new works like True Detective.

Really? Do you have any less-obvious examples?

Yes. Here are a few unconventional films with Lovecraftian elements:

- Solaris, Tarkovsky’s 1972 masterpiece of space drama and dreamlike horror.

- Dark City, a popular 1998 cult fantasy that blends a film noir plot with surreal, edge-of-madness dread.

- Pontypool, a weird, wonderful, maybe-zombie film from 2008 that inserts madness into the very language we speak. Bonus: It’s on Netflix!

- The Mist, Frank Darabont’s popular 2007 adaptation of Stephen King’s most underrated novel.

- Absentia, a low-budget, critically acclaimed 2012 horror film that only hints, in the best Lovecraftian tradition, of the horror just beyond our door. Also on Netflix.

- Kill List, an independent 2011 Irish film which, much like True Detective, takes two reluctant partners, in this case hit men, on a journey into utter darkness. Also on Netflix.

Ultimately, Lovecraftian horror is a timeless formula for blending ancient terror with the human spirit of exploration and discovery. As our ability to map the universe grows, we need Lovecraft more than ever, to remind us that some things will always remain vast and unknowable—and they probably should.

“I now felt gnawing at my vitals that dark terror which will never leave me till I, too, am at rest.”

Illustration by fiend-upon-my-back/deviantART