Spaceflight is not usually considered to be a DIY pursuit. It costs approximately $10,000 to send a single pound of payload to orbit, and the whole endeavor involves powerful explosions, high-velocity vehicles, and apex math brains. Not exactly amateur-friendly.

But that hasn’t stopped starry-eyed dreamers from hatching madcap schemes to get off this tiny planet, and occasionally making good on them. The Internet has accelerated these DIY spaceflight attempts—and sporadic successes—with many a viral video, Kickstarter project, and rocket-building tutorial detailing how anyone can carve out a little slice of the great beyond for themselves.

Read on for a 10-part history of DIY spaceships—from Wan Hu, who supposedly blasted himself to space in the 16th century, to today’s thriving amateur spaceflight community.

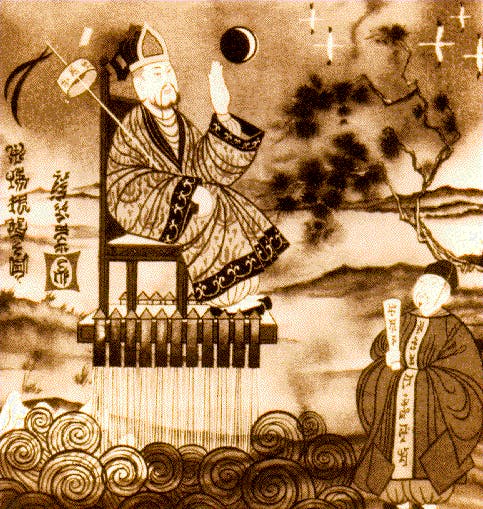

The legend of Wan Hu

According to legend, Wan Hu (which translates to “crazy fox”) was a government official who lived in China at the turn of the 16th century. Sick and tired of life on boring old Earth, Wan decided to live up to his name by rigging a chair with 47 gunpowder-based rockets, canopied by two kites. He strapped himself in, had his servants light the fuses, and vanished in the detritus of the explosion.

How great would it be if the first man in space was not Yuri Gagarin, but some random bureaucrat from the Ming Dynasty who slapped a rocketship together in a day? Though the story is likely apocryphal, Wan Hu’s legend eventually did reach outer space—a crater on the far side of the moon is named Wan-Hoo in his honor.

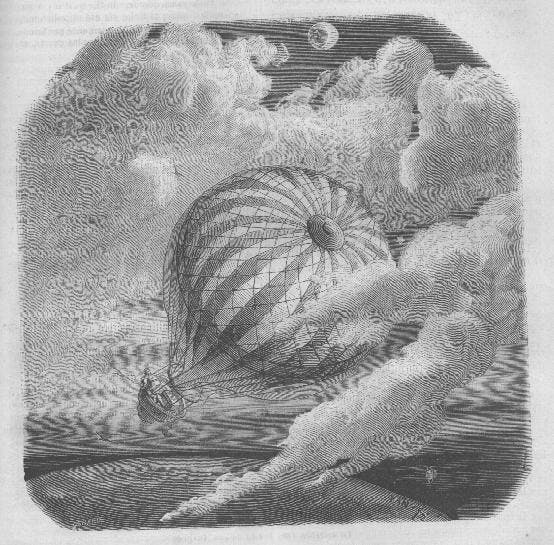

The ballooning craze

Speaking of laughably dangerous attempts to reach space, let’s talk about when humans discovered the magic of hot-air balloons in the late 18th century. The resulting frenzy over ballooning was entirely justified—after all, the skies had never been explored before.

But, needless to say, these attempts to reach extreme altitudes were beyond risky, and they quickly racked up fatalities, many of which were gruesomely public. Early ballooners also didn’t account for the hostile conditions that came with higher vistas, which nixed the technique as an option for manned spaceflight.

Regardless, balloon-powered spaceships became an extremely common trope of science fiction in the 19th century. Even Edgar Allan Poe got in on the action with his short story “The Unparalleled Adventure of Hans Pfaall,” which manages to be a space adventure, crime thriller, and hoax attempt in one. Genre-mixing level: Poe.

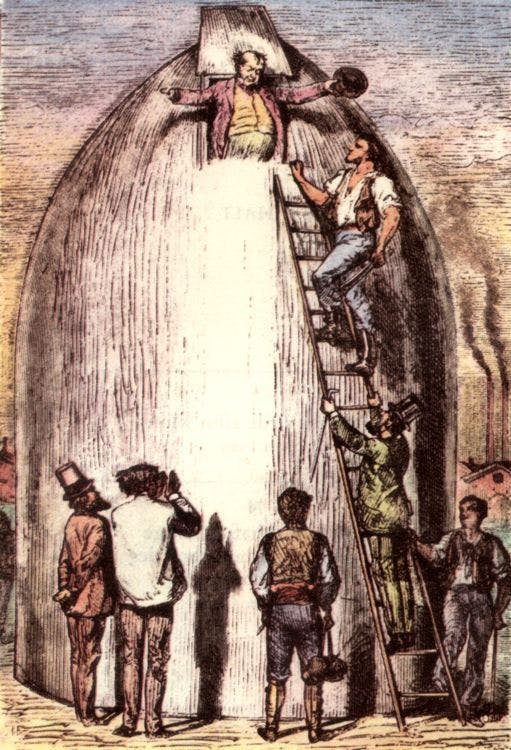

Jules Verne’s space gun

Jules Verne was so inspired by Poe’s lunar adventure story that he wrote one of his own: “From the Earth to the Moon.” But instead of a balloon-based spaceship, Verne opted for a straight-up space gun. The fictional spacecraft was thrown together by amateur engineers based out of the Baltimore Gun Club, and it was literally a giant bullet loaded into a cannon dug 900 feet deep into the earth.

As utterly nutballs as all that sounds, Verne wasn’t far off the mark—in fact, in many ways, he was downright prescient. The sophistication of the mission’s physics, which were worked out with the help of Verne’s mathematician cousin, was clear proof that rockets had potential as space vehicles. And, lo and behold, the book inspired the first serious rocketeers in history.

The first rocketeers

“Earth is the cradle of humanity, but one cannot remain in the cradle forever.” —Konstantin Tsiolkovsky

All three of the founding fathers of rocketry—the Russian Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the American Robert Goddard, and the German Hermann Oberth—were avid Jules Verne fans. To some extent, they were also DIY rocket scientists early in careers, but Tsiolkovsky embodied this “lone genius” archetype more than the others.

This was partly because he was a generation older than the other two, but it was also because of his natural reclusiveness, which prevented him from working with larger institutions. Along those lines, Tsiolkovsky built Russia’s first aerodynamics laboratory by himself and spent his life closeted in a log cabin in remote Kaluga trying to build a dirigible spaceship.

He was regarded as a total maniac by the townspeople—a real Doc Brown. His experiments posed serious fire hazards, and he once used a sail to ski down a frozen river, kind of like winter windsurfing. But as much as he freaked out his neighbors, Tsiolkovsky was the first real rocket scientist. His groundbreaking rocket equation, which bears his name, remains the passcode to space to this day.

Jimmy Blackmon’s random rocket

Jimmy Blackmon was a classic Eagle Scout.

Even after rocket science had evolved into a billion-dollar enterprise, solo rocketeers attempted to invent their own spaceships. Take Jimmy Blackmon, who randomly built an impressive six-foot rocket in his basement when he was 17, in 1957. With Sputnik looming large in the collective consciousness, Blackmon was one of many hobbyists obsessed with constructing a personal spaceship. He would also be one of many to have authority figures tell him, “Yeah, there’s no chance in hell you’re going to fly that thing.”

The ‘GoFast’ Rocket

Amateur rocketeers finally got their chance to shine on May 17, 2004, with the launch of the Space Shot 2004 “GoFast” Rocket. The vehicle was created by the Civilian Space eXploration Team (CSXT), a consortium of about 30 spaceflight hobbyists led by Ky Michaelson, and it marked the first time an amateur rocket ever reached outer space. Oh boy, though, did it ever take a lot of unsuccessful launches to get to that point, including one in which the rocket menacingly turned back on its owners.

Copenhagen Suborbitals

Copenhagen Suborbitals is an even spiffier version of CSXT, and has reached some impressive milestones since it was founded in 2008. The non-profit has launched the most powerful amateur rocket ever, the Heat-1X, though it hasn’t yet achieved spaceflight.

The company has lofty future plans to achieve manned suborbital flight with an almost entirely volunteer staff base. So if you ever want to fly on a spaceship engineered by unpaid staff, Copenhagen Suborbitals has got you covered.

The Brooklyn Space Program

In space, no one can hear you scream at Siri.

In 2010, a father-son team in Brooklyn attached an iPhone to a weather balloon and recorded its ascent 19 miles into the stratosphere, high enough to glimpse the curvature of the Earth. It bears mentioning that space proper starts at about 62 miles up, so much the pair didn’t actually break on through to the orbital side. But regardless, the fact that a curious kid and a creative parent can get a vicarious dose of the Overview Effect speaks volumes about the increasing accessibility of space.

CubeSats

Amateur rockets are great and all, but some space enthusiasts would rather outsource rocketeering to the professionals and focus on DIY spaceships instead. Answer: the CubeSat, a small cubic satellite with a volume of one liter. These lightweight satellites can be bundled into the payloads of larger launches, providing a cost-effective route for schools, research centers, and even individual hobbyists to get their experiments into space.

Multitudes of CubeSats have been launched over the last decade, from all over the world. Ecuador’s space program used one to set up a livefeed in orbit, FUNCube is an amateur radio satellite for primary school students, and Kickstarter has helped numerous DIY CubeSats receive funding. NASA is so supportive of the adorable little satellites that it’s trying to get one from every state into space.

I know what you’re thinking. You want all the CubeSats now. Here’s how to get started on your own.

The future of DIY spaceflight

Spaceflight is becoming progressively more accessible to the average citizen. Rockets, satellites, and manned modules are being designed without the help of government agencies or corporations. Even moon landings are becoming democratized—check the early success of a crowdfunded lunar drilling module on Kickstarter.

Amateur spaceflight organizations like Open Space University and initiatives like NASA’s Student Launch Challenge are further signs of the astronautical times. In fact, spaceship hobbyists are becoming so ubiquitous that governments have to actively regulate them every few months.

And for good reason, as a recent “Today I Fucked Up” post abundantly demonstrates. In a subreddit normally overrun with social snafus and financial blunders, user pasiaj confessed that he accidentally violated Russian airspace with a homemade stratospheric helium balloon.

That is one serious doozy, worthy of a “99 Red Balloons” revival. With drones now buzzing around airplanes and amateur rocketeering fails thriving on YouTube, incidents like pasiaj’s are pretty much destined to increase.

The occasional risk of inciting WWIII notwithstanding, it is well past time space was the dominion of civilians. Since we have been recognizably human, people have yearned to leave the Earth. We have finally reached the century where that is a legitimate possibility for pretty much everyone, even if it is done vicariously through a satellite. Or Twitter parody account.

Wherever Wan Hu ended up, I’m sure he’d be proud.

Photo via David Hennes/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed