Most people don’t think much of vultures, despite their vital role as nature’s garbage collectors and first line of defense against diseases. Through the absence of thought, an absence of the birds themselves has arisen; a decline of over 99 percent in the global population of vultures has left 16 of the 23 species of the bird at risk of extinction.

In order to save the species, a group of conservationists and a tech startup are teaming up to create a high-tech solution that may help bring the birds back from the brink of extinction: an artificial egg, packed with sensors that will provide a previously unseen look at vulture breeding habits.

EggDuino—the creation of a collaboration between International Centre for Birds of Prey (ICBP) and Microduino, the makers of tiny, stackable computer modules—is the very first example of a “smart” egg.

EggDuino consists of several different modules like microcontrollers–essentially tiny computers housed on a single chip—that gather and record a wealth of different data. Accelerometers and geo-sensors will be used to detect movement and rotation of the egg, while a cluster of 16 different temperature sensors tracks heat across the entire egg. A sensor and humidity sensor provide a full picture of the egg’s environment. All of that information is transferred to the cloud via a bluetooth module that can send the data wirelessly without an internet connection.

The process started when Adam Bloch, a trustee on the board of the ICBP, started to investigate the possibility of building a smart egg that could help answer questions about the incubation process to improve captive breeding.

Director of the ICBP Jemima Parry-Jones explained to the Daily Dot that while captive breeding has been done for decades, it’s a considerable challenge. “Generally eggs are more difficult to hatch in incubators if you have to take them fresh,” she said.

The typical practice is to take eggs at a third of the way through their natural incubation to improve the success rate of artificial incubation techniques. ICBP opts for incubators for a variety of reasons; “Some birds are careless with their eggs and will break them… some are not great at sitting,” she explained.

To complicate matters further, vultures are not a particularly fertile bird; they tend to have just one mate per year, and the female vulture lays just one egg at per clutch. Not only does it make for limited opportunity for successful incubation, but it also exacerbates the problem when the process fails.

“By removing that egg we can get them to double clutch and lay a second egg which doubles production,” Parry-Jones explained. That rate could potentially be improved further if the group can fine tune the artificial process to better replicate the first-third period of natural incubation.

“Technical eggs should give us a great deal of information on temperature, what is the gradient temperature through a large egg such as a vultures, how often the eggs are cooled if they are, what the outside temperature is, how often the birds turn the eggs and to what degree, humidity…and so on,” she said.

With the idea in mind but without a clear means to execute it, Bloch approached Microduino, the makers of tiny, stackable modules that house a host of technical bits perfect for data collection.

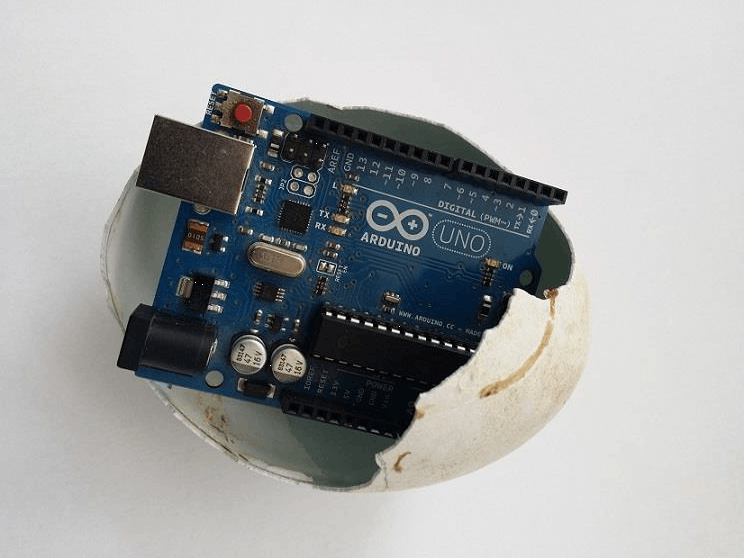

“Initially, they were trying to use the Arduino board as the main controller for the device,” Bin Feng, the co-founder and CEO of Microduino explained to the Daily Dot. But the board was simply too big. Bloch sent a picture of the problem to Feng to show that his company’s modules may be the solution to the problem.

“That picture with the comparison with the Arduino board convinced us to do this voluntarily for them,” Feng said, noting that, unlike chickens and other animals with a distinct commercial value and a considerable amount of money invested into research.

“As high-tech company persons, sometimes we forget that actually we can do something to help. This is a very meaningful project that we were able to create a complete [Internet of Things] system while giving Mother Nature a helping hand in the process.”

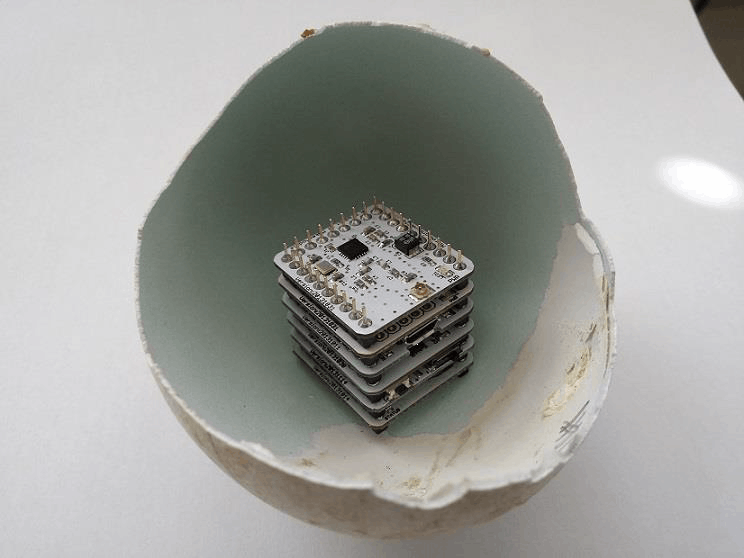

Even with the technical capabilities to make EggDuino a reality, the project was no simple task. Feng and his team had to fit a fully functional IoT system into an egg about three inches long and two inches wide.

The Microduino modules, which are about the size of a quarter and click together like LEGO bricks, made it possible to fit all the necessary sensors inside the condensed space, but still needed adequate power.

Most vulture incubation periods last between 40 to 60 days, and it takes additional time to plant the egg without disturbing the vulture in the process. “Basically we are looking for 70 days of battery life, so the power consumption for the whole system was really, really challenging,” Feng said.

His team managed to devise a solution and provide the smart egg with enough power to survive the full incubation period while storing the collected data internally until it can be transferred externally to the cloud and accessed via the web.

The egg shell is 3D-printed with a nylon material that should feel natural for the vulture. “We already tested it out, basically 3D-printed one egg, and put it inside with a vulture…She’s pretty happy with the egg, and even played with this egg. So we know for sure that our material should work,” Feng said.

The next step for the egg, following the final assembly and lab testing, will be field deployment with ICBP in Africa or India—two regions where the vulture population has been almost entirely wiped out. A successful effort with the egg, Parry-Jones explained, would improve hatch successes.

“If you look at most books on birds, particularly birds of prey, there is little accurate information on incubation periods and sometimes just guestimates, so we are often working in the dark with new species. The more we know, the better job we can do,” she said.

Feng said that to his knowledge, the EggDuino marks the first effort to get specific data about vulture incubation periods. “Vultures are a very, very smart animal. It’s really hard to somehow collect the data,” he noted.

Even with the EggDuino inching toward deployment, there are plenty of challenges for the birds beyond simply procreating more proficiently. Parry-Jones noted that ICBP, along with other organizations in the consortium Saving Asia’s Vultures from Extinction (SAVE), is working to ensure the environment is safe before releasing the birds back into the wild.

Currently, their safety is threatened by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) poisoning contracted by eating livestock that has been overmedicated with diclofenac. The drug is linked to the steep decline in vulture population. While it has been banned for veterinary use in India, drug companies continue to fight the restrictions there and in other regions.

Novartis, a Swiss pharmaceutical company, was the first to introduce the drug. According to Parry-Jones, the company has taken “no responsibility for 40 million dead vultures,” and has offered nothing in terms of monetary support to undo the damage the drug has done.

A spokesperson for Novartis told the Daily Dot that the company has never approved diclofenac for veterinary use, but noted that it is a generic medicine manufactured and sold by many companies worldwide.

“Novartis strictly adheres to government regulations that restrict the use of diclofenac and acknowledges the efforts of multiple stakeholders to protect the global vulture population,” the spokesperson said. The company is also “committed to minimizing the impact of our products on the environment and actively supports research to better understand the effects of pharmaceuticals throughout their lifecycle.”

The Wall Street Journal noted in 2011 that Novartis was one of several drug makers making a major push to sell its products the developing world, including the sale of diclofenac for human use.

Novartis has also been issued warnings by the FDA for promoting its products for use in animals that they aren’t approved for. In 2013, the company went out of its way to emphasize weight gain effects caused by an antibiotic for pigs, which makes the animals suited for increased food production, but the drug was never approved for weight gain purposes.

The hurdle of NSAID is one that will have to be addressed to truly preserve the species longterm, but for now, the EggDuino offers hope for the vulture and other endangered birds.

“We are hoping, if we’re successful with a project like this, we actually can transfer the same technology to help to save other species around the world. So it’s definitely a very meaningful project,” Feng said.

H/T Motherboard | lllustration via Max Fleishman