Opinion

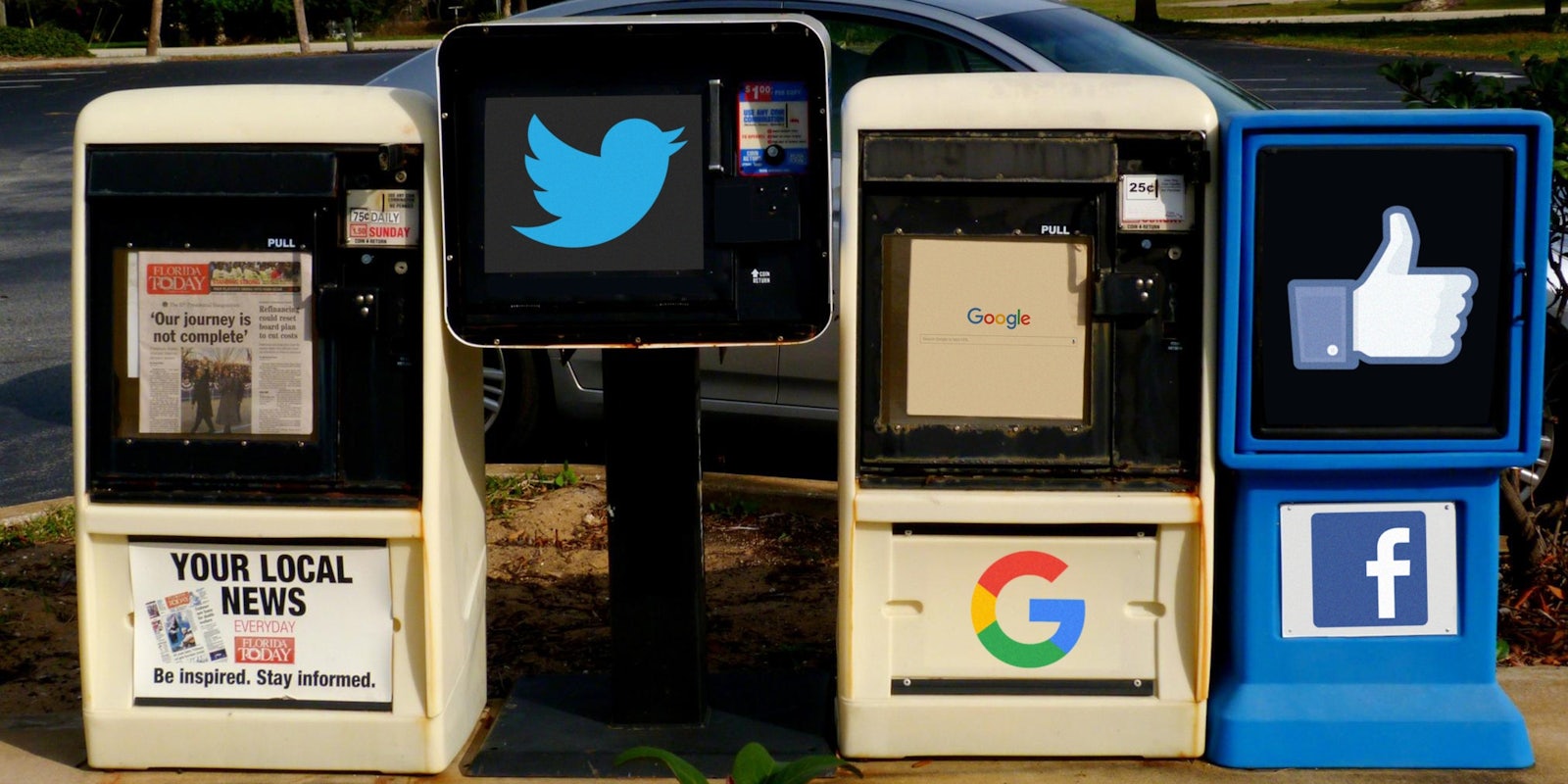

Sorry, but I don’t want Facebook to be the arbiter of what’s true. Nor do I want Google—or Twitter or any other hyper-centralized technology platform—to be the arbiter of what’s true.

But I’m glad to see platform companies at least acknowledging their role in helping spread a colossal amount of misinformation and lying propaganda. Facebook and Google have intervened in small ways, including a vow not let fake news sites make money using their advertising systems.

While I strongly believe Facebook needs to hire some human editors—the algorithm-only approach has visibly failed—I’m very leery of pushing them a lot further down a path we may all regret. But there are specific, positive steps they can take that don’t put them in the dangerous—for us as well as them—position of being the editors of the internet, which too many people seem to be demanding right now.

What are those positive steps? In a nutshell, help their users upgrade themselves.

They can help their users develop skills that are absolutely essential: namely how to be critical thinkers in an age of nearly infinite information sources—how to evaluate and act on information when so much of what we see is wrong, deceitful, or even dangerous. Critical thinking means, in this context, media literacy.

What is media literacy? From my perspective, it’s the idea that people should not be passive consumers of media, but active users who understand and rely on key principles and tactics.

Among them: When we are reading (in the broadest sense of the work, to include listening, watching, etc.), we have to be relentlessly skeptical of everything. But not equally skeptical of everything; we have to use judgment. We have to ask our own questions, and range widely in our reading—especially to places where are biases will be challenged. We have to understand how media works, and how others use media to persuade and manipulate us. And we have to learn to adopt what I call a “slow news” approach to everything—to wait before we believe any so-called “breaking news” that crosses our screens.

But even active consumption is not enough in a world of democratized media. We aren’t literate unless we’re also creators. And when we’re doing that—whether it’s by sharing a post on Facebook, writing in a blog, or starting a website or podcast or video series—we have to bring the consumer principles to the table and add some more. They add up to being honorable.

We have to be relentlessly skeptical of everything, but not equally skeptical of everything.

The flood of fake online news—augmenting the long-established river of fake news from outlets like Fox—has some of its roots in people sharing not what they know to be false, but what they believe to be true. Or, more often and perniciously, what they want to be true. If everyone did as CNN’s Brian Stelter advises, “triple-check before you share,” that would be a big help.

Why don’t Facebook and Google and Twitter and LinkedIn, among others, offer this advice themselves, and prominently? This is an opportunity the platform companies should seize. They could do more than almost anyone else to help us escape the new-media traps we’ve laid for ourselves.

The people working hardest on media literacy (and “news literacy” among other variants on the topic) are academics, activists, and ex-journalists. They’ve amply demonstrated that it makes a difference. For example, one study showed, logically enough, that exposure to media-literacy training increased students’ “ability to comprehend, evaluate, and analyze media messages in print, video, and audio formats.” Another associated it with increased “civic participation.” I could cite a long list of other studies that show media literacy’s genuine value.

I have a horse in this race; I’ve written a book about it, and have been teaching it at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism & Mass Communication. In the summer of 2015, I led a “massive open online course” (MOOC) called “Overcoming Information Overload.” A colleague in that project, Kristy Roschke, has analyzed the MOOC data and says it conforms with published research. (Note: My book is published under a Creative Commons license, and so are the MOOC course materials, which means they’re available for download, re-use, and remixing.)

For all its obvious value, media literacy hasn’t penetrated nearly as deeply as it should and isn’t being taught enough where it matters most: in our K-12 schools. In most districts it’s an afterthought, at best. And let’s be clear: In many parts of the United States, teaching real critical thinking would be considered by reality-denying ideologues to be a dangerously radical act.

Another vital cultural institution could, and should, have taken this on decades ago. I’m talking about the journalism trade.

Brian Stelter’s recent CNN commentaries have been a heartening demonstration of what media organizations could be doing. But it’s tragic and damaging—to journalists themselves as well as society—that they haven’t made this a core mission. Since they haven’t, what’s the next useful point of leverage?

The tech platforms are leverage to the nth power. That worries me. It is deeply unhealthy that a few giant companies—Facebook in particular—have become the epicenter of national and even global conversation. Their dominance is part of a re-centralization of communications that is already having dangerous consequences for freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and much more. I’d much rather see a combination of broad media literacy and a re-decentralized internet.

But their dominance exists, today. So I’m asking them to become the champions for a culture that values truth over lies, can tell the difference, and can act to help assure that truth has a fighting chance against the manipulators who are so efficiently poisoning our public discourse.

What specifically can they do? Among other things:

They can put media literacy front and center on their services. They can draw on the best work in the field—and ask for advice from super-experts like Renee Hobbs and Howard Rheingold (compared with them, I’m barely a dilettante in the field). The goal should be to help the rest of us understand why this matters so much and, more importantly, what we can do about it, individually and as members of communities.

They can give third parties ways to help users manage the information flow, not just to avoid bogus information but, crucially, also ensure that they see competing ideas challenging their own biases.

They can offer better tools to users who a) don’t want to see fake news and other lies; b) want to help online communities police themselves; c) be better organized in their own consumption of media.

Those are just a few of the many useful ways the platforms could bring media literacy to a vastly broader public.

Will this solve the problem that’s been getting worse for a long time? Of course not. But it will help. That’s a lot better than giving up and sinking further into a swamp that at some point becomes impossible to escape.

This is an emergency. Truth and context need powerful allies, and need them right now.

This article originally appeared on his personal blog and was reprinted with permission.