BY CAROLA FREDIANI

“Someone’s got a big, new cannon. Start of ugly things to come,” tweeted Matthew Prince on Feb. 10. Prince is the CEO of DDoS defense firm Cloudflare, a company whose mission is to help websites stay online when they are targeted by cyberattacks. In a process called mitigation, Cloudflare tries to alleviate the attack by filtering the data flood. But last Monday, there was quite a lot of stuff to strain. A record-breaking distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack at nearly 400Gbps hit European networks and an unnamed Cloudflare customer. The previous record, last year, was around 300Gbps and targeted anti-spam outfit Spamhaus, affecting some European Internet switching stations and slowing down some services.

Alongside Cloudflare’s alarm, Oles Van Herman, the CEO of French hosting firm OVH.com, confirmed that something big was going on. He tweeted that his company was seeing a DDoS attack far larger than 350Gbps and that attackers were using OVH.com’s IP addresses. So, despite appearances, the company was a victim and not the source.

Although it seemed that such a massive attack had not been too disruptive, it still raised concerns among the cybersecurity community. Yes, it was “just another” DDoS attack—but maybe that’s something we should be more concerned about. It’s become a commonplace Internet hiccup, but perhaps it’s the symptom of something much more serious.

•••

The first high-profile DDoS attack dates back to 1996 (here’s an interesting timeline of them), when Panix, the New York City area’s largest ISP, was almost put out of business. But even after so many years, this kind of cyberattack clearly isn’t going anywhere. In fact, they actually seem to be getting more powerful and creative, and all kinds of global players appear to be ready to use them against their own adversaries.

Cloudflare’s recent experience is not the only example of a serious DDoS attack. On Feb. 12, a handful of major Bitcoin exchanges temporarily stopped their operations after being targeted by DDoS attacks. Slovenia-based Bitstamp, the world’s largest exchange, suspended processing Bitcoin withdrawals due to inconsistent results reported by their Bitcoin wallet, adding they would wait for a software fix. “This is a denial-of-service attack made possible by some misunderstandings in Bitcoin wallet implementations,” Bitstamp wrote on its Facebook page. The attackers exploited what has been called a “transaction malleability to temporarily disrupt balance checking.”

Another large Bitcoin exchange, Bulgaria-based BTC-e, tweeted that the DDoS attack could cause delays in crediting transactions. As Gavin Andresen, chief scientist for the Bitcoin Foundation, wrote on the organization’s blog: “This is a denial-of-service attack; whoever is doing this is not stealing coins, but is succeeding in preventing some transactions from confirming. It’s important to note that DoS attacks do not affect people’s bitcoin wallets or funds.” In fact they just delay the exchanges’ ability to rapidly confirm withdrawal requests. Still they can disrupt operations and weaken trust.

DDoS attacks are certainly a rough and old-school cyberattack, however it seems they are enjoying a second youth. A growing number of actors—veteran cybercriminals, organized crimes, script kiddies, hacktivists, governments—are using them to disrupt others’ services and gaining economic or political advantages. And the fact is, they are getting bigger, stronger, and longer than ever.

Moreover, by targeting a financial service firm or an exchange platform, thus restricting its online presence and services, they could be used to attempt to deliberately interfere with market values.

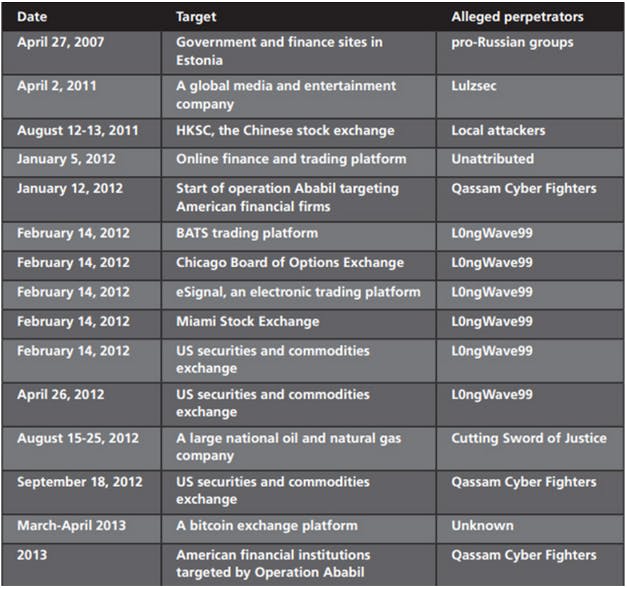

According to a recent white paper published by DDoS protection firm Prolexic, in the last few years hackers have being trying to do just that. The paper reviewed dozens of attacks that have happened since 2011, and found that some large DDoS campaigns have targeted the financial services industry, as well as other publicly traded businesses and trading platforms. Overall, the report “found a causal relationship between cyber-attacks and a change in the valuation of a company in a given market.” It also states that since 2011, and growing in 2012 and 2013, “DDoS attack campaigns have become a significant threat to financial firms.”

via Prolexic

Among the examined case studies, there were a series of DDoS attacks against American financial institutions in 2012 and 2013, allegedly conducted by Al-Qassam Cyber Fighters, known as QCF, “a group thought to be an extension of the al-Qassam brigades of Hamas.”

But on record there was also an attack against a Bitcoin exchange in April and May 2013, which is interesting because of what just happened to Bitmap and BTC-e. Since the Bitcoin economy is growing, should we expect the digital currency exchanges to be a more appealing and frequent target? The report says that during the 2013 attack to a bitcoin exchange (it doesn’t mention the exchange’s name, however it seems likely it was Mt-Gox), the assault on trading had a real effect on traders. “At times, users were unable to log into their accounts. After a 12-hour halt in trading, the exchange resumed trading. However, it was struck again, causing trading to stop once more. Panic selling occurred as did abuse of the system for profit.”

So far, the paper concludes, these campaigns have not been successful in bringing down an entire major marketplace. But just because it hasn’t happened doesn’t mean it won’t; as DDoS attacks keep getting bigger and more sophisticated, that only becomes more likely.

•••

In the last few years, reflection attacks have been especially popular and insidious. They are used to generate a massive flow of traffic against websites, since the attackers send packets with a forged IP address that makes them appear as if they’re coming from the intended victim (at least to some Internet servers). This means the target is then flooded with replies and data. These kinds of attacks usually hit domain name system (DNS) servers. However the latest reflection attack against the Cloudflare’s customer involved another technique, that is the targeting of the UDP-based Network Timing Protocol (NTP). This is normally used to sync clocks on machines, but by exploiting its weaknesses attackers can also use it to generate mass traffic against a website, so much that the site is seemingly “shut down.”

Another matter of concern, according to the Prolexic report, is the emergence of a burgeoning DDoS-as-a-Service market, where large botnets are rented to perform an attack. Such services offer “an elastic capability to ramp up or ramp down legions of botnets.” They also offer the convenience of pay-per-use flexibility, a system that offers “a la carte” services so customers can purchase customized attacks. So, if your target is big and resilient, you can just rent more bots (that is, compromised hosts) such as computers, routers, servers that are controlled by cybercriminals. And then you can start an attack by using this all-changing mercenary army.

One thing the paper fails to mention is a new actor in the DDoS scene: governments. According to the latest Snowden documents, revealed by an NBC News report, the U.K. government spy agency GCHQ cyberattacked the hacker collective Anonymous by launching DDoS attacks against their chat rooms (IRCs). These chat rooms are usually used by hackers and activists alike to communicate, and the roles were reversed when the government attacked them, making them inaccessible.

Clearly, a DDoS attack is not a tick to be ignored, despite its rather pedestrian label. It’s a weapon being used by a variety of players, for a variety of reasons. But one thing is certain: It holds more power than perhaps we’re giving it credit for.

Photo via Prolexic